Matthew Bourne/New Adventures brings the 1948 movie, The Red Shoes, to the stage.

Victoria Page (Sara Mearns) “auditions” for Boris Lermontov (Sam Archer on settee) at a party given by her aunt, Lady Nestor (Daisy May Kemp, with tiara). Photo: Daniel Coston

In 1953-54, when Britain’s Sadlers Wells Ballet had not yet become the Royal Ballet, and the company was performing in New York’s old Metropolitan Opera House in the West 30s, ballet lovers formed lines for standing-room tickets early in the morning. The excitement had, in part, been kindled by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 film, The Red Shoes, an update of a story by Hans Christian Andersen. Had anyone seen a ballet dancer as lovely as its heroine, the red-haired Moira Shearer? (Fans may have been sorry to learn that Shearer was pursuing a film career, but Margot Fonteyn was a revelation.)

Still, it’s proof of Shearer’s enduring fame that Ashley Shaw, Sara Mearns of the New York City Ballet, and Cordelia Braithwaite, who take turns in the role of Victoria Page in the Matthew Bourne/New Adventures ballet, wear reddish wigs.

To appreciate fully Bourne’s dramatic and scintillating version of The Red Shoes (just ending its season at New York City Center), you have to accept the fact that the dogmatic impresario reminiscent of Serge Diaghliev (played by Anton Walbrook in the film) now dances a bit to convey his devotion to the ballet and to the young woman he is molding into a ballerina. The budding composer, Julian Craster, who has been accompanying classes, dances to show musical inspiration overtaking him, as well as his love for Page, and his struggles with her.

The music he is writing between stints on one of the two onstage pianos is to accompany the new ballet. What we hear is not Brian Easdale’s music for The Red Shoes film (his score won an Academy Award). Instead, Bourne drew music by Bernard Herrmann from a number of movies, including Fahrenheit 451, Citizen Kane, and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir. Terry Davies orchestrated these and stitched them together skillfully. (Unfortunately, the recorded music was played at an ear-splitting volume that blurred the composer’s mastery.)

Over the course of his career in ballet and musical theater, Bourne has re-thought a number of ballet classics—not just his Swan Lake, with its all-male flock, but Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Nutcracker. His Car Man, however, was based not only on James M. Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, but on the two film versions of it. The fact that The Red Shoes was also a movie is responsible for some of the ballet’s most stunning effects; for instance, when Page loses control over the tension between marriage and the career she loves, characters from the ballet swirl and contend and overlap in ways that are almost cinematic.

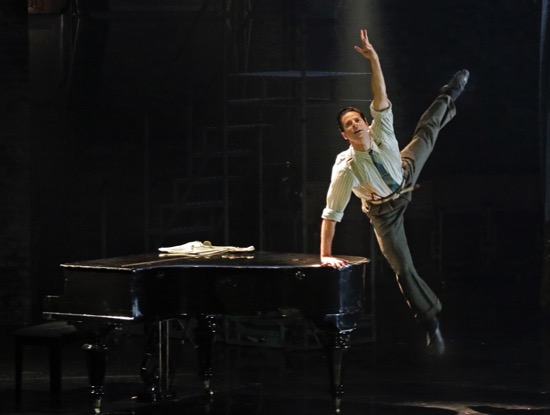

Marcelo Gomes as composer Julian Craster in the throes of inspiration. Matthew Bourne’s The Red Shoes. Photo: Lawrence K. Ho

Lez Brotherston’s remarkable set enables a variety of swift scene changes that also evoke a camera’s movements or an editor’s cutting rhythms. An ornate proscenium arch within City Center’s larger one swivels to shift the scene between a supposed performance and a backstage dress rehearsal, during which upstage footlights shine in our direction, and the dancers turn their backs to us. As Craster, Marcelo Gomes of American Ballet Theater (who shares the role with Dominic North) comes forward to congratulate the fictional orchestra that’s supposedly in front of us. And that gilded arch can smoothly convey us from Lermontov’s office to Page and Craster’s shabby London apartment, after he has been fired and she has left the company to be with him. Paule Constable’s lighting and Duncan McLean’s production design abet the scenic effects. (The one flaw, to my mind, is the fact that several seaside backdrops don’t reach to the floor, and below them, what can look like water instead mirrors the dancers’ feet.)

Although Bourne’s The Red Shoes is a full-length ballet with an intermission, the plot races along in a kind of dramatic shorthand. We don’t see love develop between Craster and Page. He impetuously kisses her by way of congratulations. After intermission, we see them strolling among the frolicking dancers at Villefranche-sur-Mer, wearing similar striped shirts, their arms around each other, already a devoted couple. The ballet-in-progress scenes involve gesticulating and kibitzing over a small model of the set, into which Ratov, the designer (Jack Jones); Lermontov’s secretary (Joe Walkling); and Lermontov (Sam Archer) peer and over which they gesticulate, most with a cigarette in hand.

In getting the performers in Bourne’s New Adventures into the nitty-gritty of the ballet world during the 1940s, the choreographer asked each cast member to research a dancer working during that period. They’re listed in the program under those names, e.g. “Svetlana” (Beriosova), “Beryl” (Gray), “Anton” (Dolin), “Frederic” (Franklin).

There’s a lot of choreography on view, not all of it great (perhaps deliberately). The aspiring Page is nudged into an impromptu solo at a party to convince Lermontove of her talent. The solo itself (performed by Mearns the night I saw The Red Shoes) is a nymphy affair, characterized by supple movements of this marvelous dancer’s torso and her suspensions of breath. We see a ballet class presided over by ballet master Grisha Ljubov (Glenn Graham) and a rehearsal of Les Sylphides (to Chopin’s Valse Brillante). The small ensemble performs a very clever beach ballet, with contrapuntal swimmers and ballplayers, that brings to mind Bronislava Nijinska’s Le Train Bleu. In Act 2, we’re treated to a brief glimpse of the mysterious Concerto Macabre, which features two-dimensional Greekish dancers and a “bull” (Graham with body makeup and a mask).

When Page has gone to London with Craster, now her husband, she gets work in a music hall, a place where two tired showgirls in elaborate feathered garments do their number shortly after two (uncredited) male dancers perform a witty pseudo-Egyptian number that includes a sort-of hornpipe, and Page is subjected to an “adagio” with two males (perhaps symbolic of Craster and Lermontov). All praise to scantily clad Mearns for bravely maintaining her self-possession while being manipulated into uncomfortable acrobatic positions.

A hellish scene in the ballet within The Red Shoes. Liam Mower dances with Sara Mearns, while Glenn Graham, between them, presides satanically. Photo: Daniel Coston

Some of the dance passages reveal feelings ingeniously. The fading ballerina Irina Boronskaya (Michela Meazza) goes through a lighting rehearsal, “marking” the steps, turning her soulful gaze toward the spotlight’s beams, while holding her Sylphide costume in front of her and manipulating it to best advantage. Gomes’s major solo begins when Craster becomes inspired by the music he’s jotting down on a page. Or maybe “intoxicated” is a better word. Gomes’s performing and Bourne’s choreography are a marvel. The later duet between him and Mearns vividly expresses the tensions that develop when both are deprived of the art that nourishes them. Their limbs tangle brutally, and both end up separated from each other and in tears.

Gomes and Mearns performed their roles wonderfully—neither over-dramatic, nor too restrained. Some of the other dancers offered a more over-the-top delivery. You could believe that the excellent dancer Liam Mower, assuming the role that Robert Helpmann played in the movie (Page’s dance partner, Ivan Boleslawsky), would be given to dramatic gestures (I never understood why he —and Helpmann— also portray a minister in the ballet within a ballet; maybe this village considers dancing to be the devil’s business and need to exorcize him). Although Graham impressed me mightily as a dancer, I was put off by his approach to the Massine role during rehearsals and “discussions.” With a rigid spine and a snooty uplift of his chin, he seemed a caricature of the stern choreographer and ballet master.

The priest (Liam Mower) comforts the dying heroine (Sara Mearns) of The Red Shoes ballet. Photo: Daniel Coston

Defining an onstage ballet within a movie is easier than defining an onstage ballet within an onstage ballet of the same name. When a black-and-white panorama of a small village slides across the back of the stage, and new wings descend to frame the stage, we spectators have to understand that we’re seeing the finished work in which Page stars. Its population is also garbed in black and white, whether the dancers are portraying dagger-sharp men and women or sailors and their girls. Ballet Master Graham doesn’t seem to play the shoemaker who crafted the dangerous slippers, but a devil (small, barely discernible horns and lots of red lighting). As Victoria Page, the newly minted star, Mearns wears a red velvet bodice and overskirt surmounting a billow of white petticoats. Tempted by the diabolical Graham, she dons the red shoes and begins the endless dance they compel her to perform.

Exciting though this is, you might need to review the 1948 movie to be absolutely sure of what you’re seeing. Certainly the heroine’s plight is evident: unable to shuck the shoes, she gets tired, wobbly; her hair comes down; her dress becomes ragged and filthy. Her lover (Mower) seeks her, but neither sees the other until it’s almost too late, even though the two are dancing near each other. The shoes come off. She dies. The crowd (we’re joined by recorded cheers) goes wild. At the end of Act 2, when Vicky throws herself under a train (a convincing, smoke-belching locomotive heading for the audience), it’s Gomes who takes off the hastily tied slippers and cradles her in his arms. And this time, the cheering is all ours.

I am an enormous fan of the film The Red Shoes, which I saw for the first time at the Waverly Theater in the Village in 1951, where it was being shown as a revival. I was 13, I told my parents where I was going, and when I’d be back from the first matinee, and then I was so entranced I watched it over again and was very late getting home and heard about it. So I have been ambivalent about seeing Matthew Bourne’s theatrical version and after reading this vividly written review, I do not regret frankly that I probably won’t see it since it’s unlikely to tour to Portland. I would have loved, however, to have seen Mearns and Gomes as Victoria and Julian.

And I love Deborah’s framing of the review, the vision of her standing (or sitting) in line to see Sadler’s Wells perform in 1953-54, when I did not see the company, although I saw Moira Shearer in Cinderella, and Fonteyn in Sleeping Beauty in 1948 or 9 when the company came to the U.S. the first time. I was ten. I’ll say no more.