New York Theatre Ballet’s Legends and Visionaries series at Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church.

New York Theatre Ballet in the dress rehearsal of David Gordon’s Beethoven/1999. (L to R): Carmiella Lauer, Elena Zahlmann, Steven Melendez, and Amanda Treiber. Photo: Robert Altman

The cover photo for New York Theatre Ballet’s season at Danspace Saint Mark’s does not show any of the company’s fine performers. Instead it bears a photo of artistic director Diana Byer and David Vaughan, the dance historian, critic, lecturer, and performer widely known as the author of Frederick Ashton and His Ballets and Merce Cunningham: 50 Years. On October 27th, six days before the company’s performances began, Vaughan (David to hundreds of us) died at the age of 93, still hoping to finish his biography of James Waring.

In her pre-performance speech, Byer emphasized that these performances by NYTB were dedicated to Vaughan. At all three, she would read the loving words sent by British choreographer Richard Alston, who had been befriended and mentored by Vaughan when he arrived in New York years ago to study at the Merce Cunningham studio, where Vaughan worked as the company archivist.

Vaughan’s connection with NYTB was perhaps inevitable. Byers studied with Antony Tudor and Margaret Craske, and her small company, with its treasure chest of a repertory and a commitment to performing every ballet with its particular style and spirit in mind, has revived chamber works by Tudor and Ashton—works beloved by Vaughan and well known to him since his days as a young balletomane in his native Britain.

I’m sorry that he couldn’t be with us in Saint Mark’s Church. As in all the company’s “Legends and Visionaries” programs, NYTB offered a potentially heady mix of styles that had more in common than you might think. Imagine this. José Limón’s modern classic, the 1949 La Malinche, staged by Sarah Stackhouse; a new duet, Optimists, by American Ballet Theatre dancer Gemma Bond (her third for NYTB); Beethoven/1999, postmodernist David Gordon’s re-envisioning of some of his own earlier material; and a revival of Alston’s A Rugged Flourish, made for NYTB in 2011. None of these works was crass or showy or muddle-headed. All required that the dancers be aware of one another in this space, where intimacy with us was also a given.

New York Theatre Ballet in José Limón’s La Malinche (dress rehearsal): Steven Melendez and Elena Zahlmann. Photo: Robert Altman

Limón choreographed La Malinche for the small company he had formed in 1946, with Doris Humphrey as his artistic advisor. Interestingly he structured the piece the same way Martha Graham had designed her 1940 trio, El Penitente. The three performers march onstage in a procession, dance in unison, enact a story, and rejoin festively when it’s over.

The story, linked to Limón’s roots in Mexico, is one of complicated alliances. La Malinche was the name by which history and legend remembered a young woman, one of twenty female slaves bestowed on Hernando Cortes in 1519 by those he had conquered, and who were instantly baptized into the Catholic faith. She became his mistress and his interpreter and died young. Artworks of the period show her by his side.

Limón compressed this tale into one of shifting relationships among La Malinche (Elena Zahlmann), El Conquistador (Steven Melendez), and El Indio (Joshua Andino-Nieto). Norman Lloyd’s wonderfully spare, expressive music is performed live by Anna Laurenzo (mezzo-soprano) Thomas Verchot (trumpet), Jeremy Smith (percussion), and Michael Scales (piano).

Joshua Andino-Nieto and Elena Zahlmann of New York Theatre Ballet in José Limón’s La Malinche. Photo: Robert Altman

Melendez carries an immensely long sword that also suggests a crucifix, and his relationship with Zahlmann is made clear by the way he slides the sword across and beneath her back as she kneels, and uses it to lift her to her feet. He swings and thrusts the sword about, puzzling and alarming her. Still, although she takes the sword and uses it to draw a circle around herself, she also dons a long, open-front skirt and carries a handkerchief—a “lady” now.

Andino-Nieto, who has remained on his knees, his back to us, now denounces her, pushing her toward a corner and it’s Melendez’s turn to wait at the side, alert but quiescent. But the choreography eloquently, and with the clearest of lines, shows how the traditions shared by El Indio and La Malinche draw her to him. As they dance together, their feet begin to pound the floor rhythmically and their hands to clap. Their sheer united force causes Melendez slowly to collapse to the floor, and Zahlmann takes back her flower, which he had affixed to his sword, and gives it to Andino-Nieto. End of story. The three, who have performed this beautifully, join in a celebratory dance.

Amanda Treiber and Erez Milatin in Gemma Bond’s Optimists. Photo: Robert Altman

After Scales has treated us to a virtuosic piano interlude, Bond’s Optimists begins. It’s well-titled. Any dancer wishing to bring off this rapid, intricate storm of movement would have to be an optimist (yes, the duet might have benefitted from some quiet moments). The music—the third “Vivace” section of Sergei Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata No. 8 in B-flat major, op.84—goads the two on. Amanda Treiber and Erez Milatin are excellently paired—the same size and equally nimble, even acrobatic in the modest way the choreography mandates. They dance like playfellows, both cooperative and combative.

Watching them, though, I began to wonder why Treiber had to be wearing pointe shoes. O.K., Bond wanted some skimming bourrées, and they look less attractive on half-toe. Still, I thought that the very presence of the shoes lured this talented choreographer into bits of conventional pas de deux partnering that looked somehow out of place in this bright little ballet.

(L to R): Amanda Treiber, Steven Melendez, Carmella Lauer, and Elena Zahlmann in David Gordon’s Beethoven/1990. Photo: Robert Altman

The NYTB dancers faced another kind of challenge in Gordon’s Beethoven/1999. In this, the music becomes. . .what?. . .a fact of life, a stream to be dipped into as it run by. It’s a recording of Beethoven’s String Quartet no. 16, op. 135, and its striving becomes that of the four dancers, whose space is limited by four portable ballet barres. Camilla Lauer, Treiber, and Zehlmann wear short, printed dresses; Melendez is clad in pants and a rust-colored t-shirt. They might be going to a picnic on a fine day, say in the 1940s. Their movements are pedestrian—walking, running, crouching, sitting. No fancy footwork. Sometimes they travel in a squad, sometimes they assert their individuality. What becomes crucial are their gazes and their gestures. Often, as they go or pause, they raise one arm, as if shielding their eyes from the sun. And are they now hailing someone in the distance? Sometimes they group themselves attractively; perhaps some invisible pal (us?) has whipped out a camera. At other times, they hint at relationships. Which two are girlfriends? Which woman does Melendez prefer?

In the end (since the church has no wings), they exit by walking out of the fenced-in area toward the altar and sitting on the steps in front of it. Lauer is the last to go, and her far-seeing gaze movingly sums up an awareness of the longing in the music, which these four friends recognize and honor.

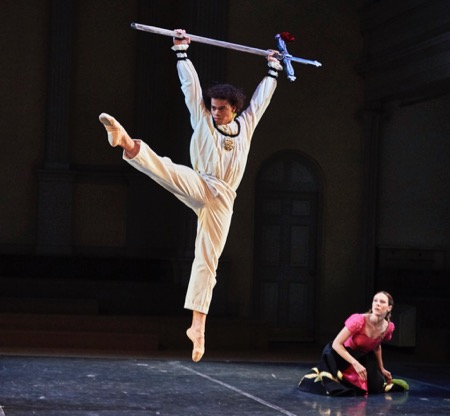

Mayu Oguri and Steven Melendez of New York Theatre Ballet in Richard Alston’s A Rugged Flourish. Photo: Robert Altman

The only problem with watching Alston’s A Rugged Flourish is that the church is so full that certain spectators along one side have to crane to see the action past Alexis Branagan, Dawn Gierling Milatin, Monica Lima, Mayu Oguri, Lauer, and Treiber, who wait in front of them (supposedly offstage). Katy Atwell’s lighting, excellent for all the pieces, can’t tell us not to look at them.

Alston’s title is apt in terms of the music. Aaron Copland Piano Variations, rolled out by Scales, is indeed rugged and flourishing—sometimes halting, jolting, sometimes flowing, rippling, gushing. Alston’s program note defines its quality as a “brave stony rigour.” The choreographer also identifies the subject of his dance as portraying a young hero, brave enough to be alone, yet finding new strength and pleasure in company.

Melendez is clearly on a voyage of discovery, leaning down to touch the floor, as if learning from it. In fact, he dances as if that was also his aim as a performer, which I find remarkable. His power is almost catlike, huge jumps erupting out of nowhere, and he is always aware of the space around him, as if seeing it for the first time.

I still can’t quite abandon my impression of the piece when I first saw it in 2011. Despite the fact that the hero is learning about the world and embracing what’s good about it, the ballet, for me, harks back to Vaslav Nijinsky’s 1913 L’Après-midi d’un faune. The costumes (designed by Sylvia Taalsohn Nolan) make me envision the six women, in their identical filmy, pale green dresses, as a bevy of nymphs who’ve discovered a stranger in their territory. They regard this male with interest, but are so similar in their pretty behavior and slightly fevered bourrées that it seems accidental when he chooses Oguri to be his partner and teach him a little something more intimate. Nothing wrong with that, but. . . .

The women of Richard Alston’s A Rugged Flourish. (L to R): Alexis Branagan, Monica Lima, Amanda Treiber, Carmllla Lauer, Dawn Gierling Milatin. Photo: Robert Altman

I mentioned intimacy earlier, as an inevitable factor in performances in Saint Mark’s. NYTB is a small treasure in New York’s ballet world, and seeing the dancers’ skill and fine-tuned performing at close range only heightens our pleasure.