The Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company presents a new work.

Bill T. Jones’s A Letter to My Nephew. Penda N’diaye and I-Ling Liu walk the runway together. Photo: Stephanie Berger.

In October, almost a year ago, I wrote about one of two pieces that the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company premiered at the Joyce Theater. Lance: Pretty AKA The Escape Artist told through movement, speech, music, movable set pieces, and props the story of Lance T. Briggs, a nephew of Bill T. Jones, who began as a promising ballet dancer, became a model, a songwriter, a drag queen, and gradually entered the grim limbo of drug use, gang fights, injury, imprisonment, and worse. I ended my somewhat puzzled review thinking that Jones was presenting “experiences unsettled by memory or liquefied by drugs.”

Yet in retrospect, Lance: Pretty AKA The Escape Artist was a model of clarity compared to the company’s BAM Harvey Theater premiere, A Letter to My Nephew. It’s as if co-choreographers Jones and associate artistic director Janet Wong, plus the nine terrifically creative dancers, had taken selected elements of the earlier piece, shaken them up, and embedded them in a new structure. The result is exciting and pungently dramatic most of the time, although at some point, I started to wonder how long it was going to last.

Answer: It goes on until the projected letters spelling “Dear Nephew,” which appeared as the piece began, are finally followed by, “Love, Your Uncle.”

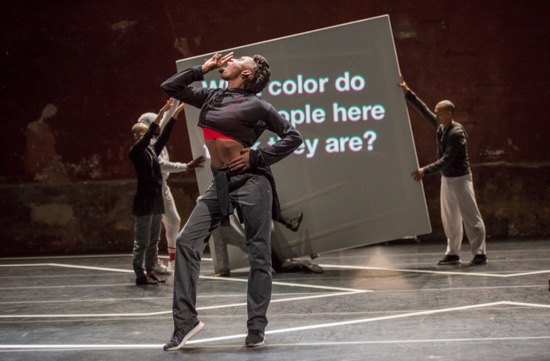

Penda N’diaye in Bill T. Jones’s A Letter to My Nephew. At back (L to R): I-Ling Liu, Vinson Fraley, Jr. (partially hidden), and Huiwang Zhang. Photo: Stephanie Berger

What’s between these is not so much a letter as Jones’ imaginings of Briggs’s collapsing world. His strong sense of form involves repetitions across distances (remember when I-Ling Liu first got thrown by a clump of men? Is Huiwang Zhang, who spins while holding the huge, square white “wall” overhead, the same person who did it the first time?).

Movements and groupings echo one another as unsettlingly as the reverberations that Samuel Crawford’s sound design creates in the score that’s vividly performed by composer-keyboard player Nick Hallett and singer Matthew Gamble. And, in fact, Jones’s collage of repetition and fragmentation does evoke a life going in circles. But whose life? If you hadn’t seen the earlier work or read the program material between the lines carefully, you might wonder about the identity of the man who has the last word in a close-up projected video. Does he match the dancing “protagonist” (Vinson Fraley, Jr. and perhaps others) through whose torn-up life we have been traveling? The man speaks so rapidly that he’s hard to follow, but through his curses and angry memories and his final sweet regret, we can believe he is the nephew.

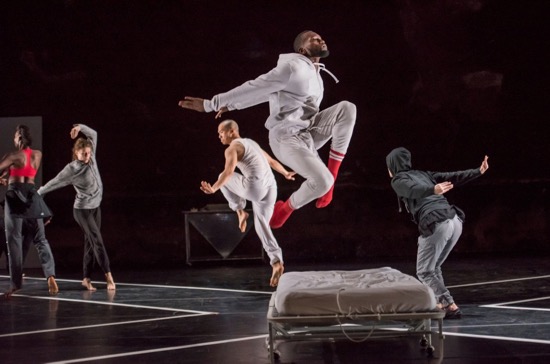

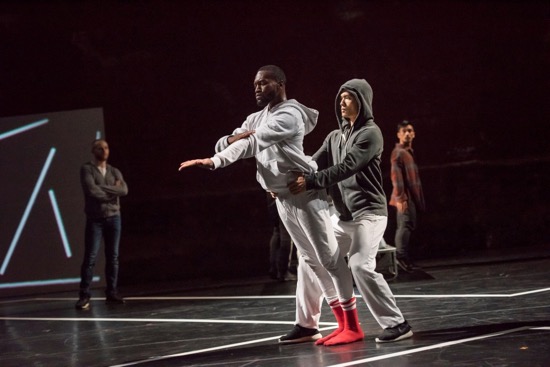

Dressed in white sweatpants and a white, hooded sweat jacket, Fraley stands out in the crowd, and his red socks draw our attention to the tiptoe strut with which he vogues down one or the other of the crooked x-shaped paths in Björn Amelan’s set. (These paths from corner to corner, outlined in white tape and by Robert Wierzel’s lighting, become models’ runways, although few people who pass along them do the expected strut.) Zhang, who also wears all white clothing part of the time, may be a surrogate. His solo is a heart-stopping display of a strong man’s falling apart. He trembles as if he can’t control his legs, but thrashes the air and hurtles through it as if beset by invisible forces.

Members of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company in A Letter to My Nephew. L to R: Carlo Antonio Villanueva, Penda N’diaye (hidden), I-Ling Liu, Huiwang Zhang, Barrington Hinds, and Vinson Fraley, Jr. Photo: Stephanie Berger.

These people are fierce, fighting for turf they may not even know they’re on. It’s all but impossible to follow individuals in a melee that involves painful-looking wrestling, punches, yanks, kicks, head-over-heels falls: Fraley, Barrington Hinds, Shane Larson, I-Ling Liu, Penda N’Diaye, Jenna Riegel, Christina Robson, Carlo Antonio Villanueva, and Zhang. An impossible shared task in which all are courageous. Never mind that Liu is a tiny, tough woman and N’Diaye is tall and elegant and that three of the men are bigger than they are. All take their falls; all give as good as they get. What are they fighting for? Maybe they don’t even know.

The streetwise costumes by Liz Prince may be layered or stripped down. The environment is a shifting one too. Projections turn the back wall into a scabrous one partway through the piece. Words snake across it or appear on a flat white square when it’s set on edge. Two poles held horizontally at either end dip down or lift high, making the dancers passing between or through them seem to be diving through waves. Eventually, a number of longer poles build a box into which all nine people several times rush, pose as if in a crowded cell, and dash out from it again.

A Letter to My Nephew. L to R: Penda N’diaye, Christina Robson, Huiwang Zhang, Vinson Fraley, Jr., I-Ling Liu. Photo: Stephanie Berger

A white-sheeted cot that is periodically brought in folded; unfolded; left for a while for people to lie, sit, or stand on; then folded up and carried away. Anyone watching Lance: Pretty AKA The Escape Artist last year would have understood “hospital” and “prison.” This year, we have no such clues, but may presume, or remember, that “Lance” moved around a lot.

The musicians and assorted recorded sounds (once: helicopters) are terrific at evoking place, mood, and atmosphere. Robbie Tronco’s “Walk for Me” underlines (somewhat ironically) runway parades. Sam Cooke’s “Bad Boy/Having a Party” fits the action perfectly. I’m not sure what Thomas Ravenscroft’s Elizabethan round “Joan, Come Kiss Me Now” suggests in a haunting arrangement, except that it suits the blurry carousel of life onstage; Jean Renoir’s “Parlez-moi d’amour gets a similar knocked-around treatment. Hallett has also set some of Briggs’s lyrics to music.

Disasters and violence—from the Florida hurricane to the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia—find their way into the atmosphere via projected words and sentences. A loop of a car set on fire plays on a small hanging screen. We hear the third, all-but-forgotten verse of our national anthem, a verse now perceived as racist. These elements pack a heavy load onto Jones’s message to his nephew, although racism was for sure something that Briggs encountered during his difficult life.

Bill T. Jones’s A Letter to My Nephew. (L to R): Shane Larson, Vinson Fraley, Jr., Huiwang Zhang, and Carlo Antonio Villanueva. Photo: Stephanie Berger

There’s a lot of dancing in A Letter to My Nephew. Jones’s recorded voice counts out numbers that may be about more than just keeping the dancers in time. Once he gives his orders in the manner familiar to dancers everywhere (one-two-three-four, two-two-three-four, three-two-three-four, etc.) Without warning, the nine, suddenly elegant, pose their way into an adagio of the sort that every ballet teacher includes in a class. They launch into leaps and beat their legs together. At another moment, they let loose with steps they might do at a party or in a club. Or they hunker down—feet wide apart, knees bent, shoulders hunched—as if a potential fight lurked around the next corner.

Some of the choreography is symbolic of erotic complications or conflict—either with life or the body itself. Down on the floor, Villanueva grasps one ankle behind him and goes on to tie himself into knots. Zhang has a similar, battle with himself, and the two of them mingle in more complex and contrary entanglements. Three couples perform, in canon, a standing-in-place duet that also creates images of intimacy and contention. Riegel, hooded throughout, dances as if her skin were coming off. Robson keeps scratching an itch that won’t go away.

However much A Letter to My Nephew is trying to tell us, these dancers are all deep inside the work, believing every moment. I can’t praise them enough.

I love reading your reviews always! Just wanted to add – when I saw this piece, I could not help remembering the earlier Analogy piece as well, and thought that I had enjoyed that one more. I still enjoyed this one, particularly moving was the push-pull movement between two women a little more than half way in. That part reminded me of some of Bill’s early work with Arnie – some things I was lucky to have seen a little while back at the Queens Theater. I also noted that each time we heard Bill counting, he counted from one to 45, significant perhaps because it’s how many presidents we’ve had? I don’t know, but the current-event bits made me think this way. Also – at the performance I attended, one of the most rousing parts was during ovations at the end, Bill came out and led the group in some clap/stomp energetics. I hope we can see more of him in action!