Twyla Tharp Dance appears at the Joyce Theater, September 19 through October 8

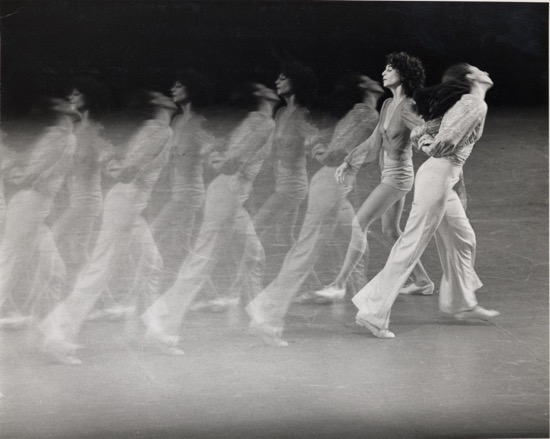

Twyla Tharp’s The Raggedy Dances in 1972. Heading left: Sara Rudner. Heading right: Rose Marie Wright. Photo: William Pierce

What do I admire—love— about Twyla Tharp’s best choreography? Its scrappiness, its heroism, its tenderness, her masterly way with form and dynamics. She knows how to make a tight, punchy barrage of little steps erupt into a slow soar, how to turn a canon into a fugue, how to let unison slide into diversity and out again. Keep your eyes open! That dancer slinking into jazzy ease may bolt any second into a multiple pirouette with no apparent preparation.

The program that Twyla Tharp Dance is showing at the Joyce Theater through October 8th boasts two of her early works: The Fugue (1970) and The Raggedy Dances (1972). The company is smaller than it was for Twyla Tharp’s 50th Anniversary Tour in 2015.

However, it only takes three dancers to perform The Fugue, which Tharp composed for Sara Rudner, Rose Marie Wright, and herself. In later years, men often took it over. At the Joyce, two women and a man perform Rika Okamoto’s staging: Kara Chan, Kaitlyn Gilliland, and Reed Tankersley. They wear no-nonsense attire by Santo Loquasto, belted black trousers, long-sleeved black shirts, and medium brown boots that point up the fact that the stage floor they punish is mic’d.

You could transcribe their actions onto a blackboard, and I’d still need a course to help me decipher their twenty 20-count variations. A dog might as well have shaken to pieces a page of notes about it. I don’t, though, mean to imply that the structure isn’t pristine. The dancers walk to new places to begin a new variation; they end each with the equivalent of a period. The elements of the theme, however, are subjected to being turned upside down, dissected, performed in retrograde, divided, reunited, re-ordered, slowed down, speeded up. I can’t keep track.

All three expert dancers are not always onstage together; one or two may leave, return. There’s no music. When they embark on a variation, only their eyes and the sound of their feet keep them in time with one another. To begin a section, one of them will sometimes slap out a four-counts-for-nothing against his/her thigh, or say it aloud. They’re not out to charm us. The Fugue is a challenging task, a track they’re simultaneously laying out and riding along, and we marvel at the visual and aural complexity of it.

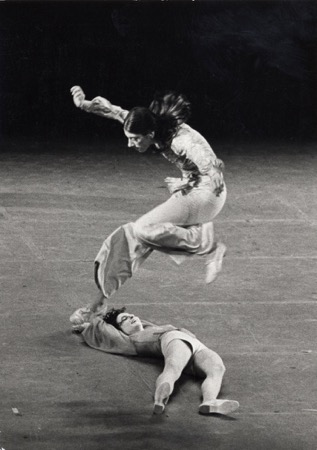

The Raggedy Dances in 1972. Rose Marie Wright jumps over Sara Rudner. Photo: William Pierce

By contrast, The Raggedy Dances, which opens the program, has a mischievous streak. Loquasto hasn’t attired the five dancers alike. Gilliland, for instance, wears a red jumpsuit, Kellie Drobnick a knee-length blue dress. The piano rags by Scott Joplin, Charles Luckey Williams, and William Bolcom (marvelously played by Joseph Mohan) slide and romp and tease, as if this were a rambunctious party. The dancers move their hips, shoulders, and heads with insouciant ease, digging down, shimmying around. But they also spin and swing their legs high; two may jitter around each other as if in playful combat. Occasionally people get dizzy, stagger, look as if they almost might throw up, but recover quickly.

The opening, suavely jabbering duet by Gilliland and Daniel Baker offers a nice joke. Their movements carry them offstage, and, as Mohan continues to play, you can hear the faint sound of footsteps as they race behind the cyclorama to reappear from their original entry point. It’s as if they’ve been sucked back on, or the stage is a honeypot and they’re bees on the rampage.

Tharp’s superb dancers have been coached by two members of the original cast, Rudner and Wright, and rehearsed by Okamoto. The performers make what must be strenuous look easy, at times impulsive. Chan and Drobnick pair up for one rag, Baker and Matthew Dibble for another. Drobnick reappears in softer light (by Jennifer Tipton) to perform to Joplin’s “The Entertainer;” she’s wearing a little black shawl over a black outfit that bares her legs, This is the number that Tharp danced in 1972, wearing what I remember as a purple bikini. Back then, I wrote of her: “She dances for a long time, looking with every passing minute smaller, lonelier, tireder. A stripper seen through the wrong end of a telescope, more concerned with scratching some sly private itch than with ingratiating herself with an audience.” Drobnick is taller, more elegant, more dreamily sensuous within the music that ripples around her.

The audience gets a surprise midway through the shenanigans. Pianist Mohan’s fingers travel back several centuries to Mozart’s 12 Variations in C major, K. 265, on the French children’s song “Ah, vous dirai-je Maman,” The theme is deceptively simple, but, oh, those variations! Chan and Baker tackle the music with marvelous aplomb—calming it, racing with it, dancing alone, dancing together, he manipulating her, the two of them stepping hand in hand. They’re a treat to watch. Chan, new to me, is a small woman who dances big. She has a wonderfully flexible spine that comes in handy when she breathes her way into a rapturous turn.

Then everyone explodes onto the stage and Joplin is reborn.

In 2006, Tharp wrote, directed, and choreographed The Times They Are A-Changin’. That Broadway show incorporating Bob Dylan songs was not a smash hit, but Tharp must have a soft spot for his music.

I’m guessing that her second, more modest venture, a world premiere titled Dylan Love Songs and set to recorded music, has been through some in-process changes. The Joyce program lists five dancers. A program insert lists six. Drobnick is not in what we see, and Okamoto is. John Selya has been added to the cast. The dance itself is enigmatic and a bit unsettling. I’m not sure I understand what guided Tharp’s creation beside the music: seven songs by Bob Dylan. Some are familiar to me (“You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” and “Shelter from the Storm”), some not. I can’t remember ever hearing “Jokerman,” and only upon looking up the words Dylan slurs, did I discover how dark they are despite the peppy tune.

A small curtained structure sits at the back; dancers can disappear behind it and emerge from it. Jennifer Tipton’s lighting casts their shadows on the cyclorama, sometimes doubling them so a single image can acquire a twin on the other side of the structure. There’s a lot to take in and puzzle over. Tankersley and Gilliland are sometimes paired; so are Chan and Dibble, and the piece showcases some astonishing solo dancing. Selya prowls around the stage, watching and interfering, often spot-lit; he’s garbed in a long, black overcoat, most of the time sporting a fedora that shadows his face,.

Is he channeling Dylan? I can’t say He places a floppy hat on Gilliland’s head, as if bestowing an honor (or. . . ?); she wears it as she struts elegantly across the stage a little later. Tankersley dances while vigorously manipulating a black-and-white striped shirt. A couple of hats get worn, but no stand-up routine materializes. Backed by Chan and Gilliland, Dibble sheds his jacket to dance aggressively, eyeing us, while Selya mucks around with something in a corner. It turns out to be a piece of black plastic that he ties around Okamoto, making her look even stranger than does her disconcerting hair ornament in a pas de deux (lifts and all) with Dibble. Selya dances alone, to a heavy beat, wrenching himself around, wonderfully weighted, juicily shifting dynamics. When Okamoto dances with him, she becomes tougher. Tankersley performs a solo (his second) magnificently. Tipton turns the backdrop purple. Selya takes down the curtain on its pole and swings it around. Shadows proliferate.

Reed Tankersley dancing in Twyla Tharp’s Brahms Paganini Book II at the Joyce in July 2016. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Since for some unfathomable reason, no photos of the dances were available, I’ll explain that Loquasto’s costumes in shades of black, gray, and brown (with a slightly pink vest on Baker) seem deliberately clunky, as if to suggest that these people have raided attics and thrift shops and coordinated their finds. Okamoto wears the aforementioned headdress, a short, speckled dress with a halter top, an elastic belt, and, at some point, cowboy boots.

Another addition to the program was identified as Entr’acte. Involving music that ranges from Blind Willie Johnson to Franz Schubert, it’s like a crazy vaudeville put on in haste, a tray of various hard-to-identify hors d’oeuvres. Tharp talks to us and shows us how smart her dancers are at interpreting barked-out on the spot instructions, mentions God, and banters with Selya, who speaks intermittently in French and German. I hear one of the two say, “You never liked me,” and the other answer, “My mother never loved me.” When he picks Tharp up and carries her offstage, she screams (the audience adores it).

More power to Tharp for loving the old limelight. She’s 76 and spry. She can shake it as smoothly as she wishes. We may fear for her when Selya turns her upside down in their duet, but she’s game. When a crowd of others arrives to help, she walks up his bent back to queen it over the stage for a few seconds. Some chicken references emerge via flapping of arms and crowing. What’s that about? Dunno. A reference to her 1977 Cacklin’ Hen? Does her history play a role in this “entr’acte? Her biography? Oddities have cropped up in her career before.

See it for yourself. And, of course, relish what preceded it: The Fugue! The Raggedy Dances!

Twyla Tharp embodies the conflict that every artist in America faces: the need to be both avant garde and popular at the same time. Could this be yet another phase in her highly varied and illustrious career? It is so valuable to have someone who writes so well and who has also been witness to the entire body of work.