Karole Armitage, Jaqulyn Buglisi, Elisa Monte, and Jennifer Muller join forces.

Elisa Monte’s Day’s Residue. Left rear: Clymene Baugher. Foreground: Scott Willits jumping over Thomas Varvaro. Behind them: Wade Watson, jumping over Alrick Thomas. Photo: Darial Sneed

As the intermission is winding down, and enthusiastic spectators have resumed their seats, the five choreographers presenting works this June evening walk onto the New Live Arts stage and introduce themselves to us: Karole Armitage, Jaqulyn Buglisi, Elisa Monte, Jennifer Muller, and Tiffany Rea-Fisher (Rea-Fisher, now the artistic director of Elise Monte Dance, is the youngest of the group). Some of the women limp very slightly or walk stiffly, if elegantly. They’ve clearly paid their dues as dancers and as choreographers, and the audience lets them know how cherished they are.

The first four are firmly positioned in the history of modern dance in America; Buglisi and Monte performed in Martha Graham’s company while Graham was alive; Muller and Armitage danced in the companies of giants of the next generation—Muller with José Limón, Armitage with Merce Cunningham. They’ve been choreographing for three or four decades, and their companies continue to be lauded on the international scene.

Muller plays host at this intermission moment, making it clear that the evening is not a showcase, but a collaborative venture, the fifth since 2013. (The roster has changed slightly over the years; Armitage is a newcomer.) You might also consider the season at New York Live Arts as a sampler—a good way to see the work of choreographers you admire and to become acquainted with ones unfamiliar to you.

Jaqulyn Buglisi’s Moss 1. Leaping (left to right): Jessica Sgambelluri and Terri Ayanna Wright. Photo: Darial Sneed

I didn’t notice that the program information for Buglisi’s Moss 1 (one of a projected series) lists five subsections: Filament, Circle of Stone, Stalk, Capsule, and Boundary Layer. I also puzzled over the ways in which what I was seeing could have been inspired by R.W. Kimmerer’s Gathering Moss and Braiding Sweetgrass (acknowledged in a somewhat puzzling program note). To intriguing music, played live by composer Paula Jeanine Bennett (percussion and vocals) and Christopher Lancaster (guitar), eight women (including Brenna Monroe-Cook as a guest artist) enact what has the air of a ritual, and A. Christina Giannini’s costumes present them—with some subtlety—as women warriors.

They dance with power and spirit—coming and going—sometimes brandishing wands or poles. You can see the Graham influence in their ceremonious walks, occasional contractions of their ribcages, and the way they step onto one leg and, tilting sideways, lift the other leg high to the opposite side. Had I understood that Moss I is essentially a suite of related numbers and not been taken in by its ongoing flow, I wouldn’t have become as confused as I did, wondering where all this dancing was leading.

Seven cast members of Day’s Residue: Maria Ambrose, Clymene Baugher, JoVonna Parks, Alrick Thomas, Thomas Varvaro, Wade Watson, Roxanne Young. Photo: Darial Sneed

I first saw Elisa Monte’s Day’s Residue (2000) at her company’s 25th anniversary season in 2006, and it’s perhaps then that I got the information that it was set to two sections of Vladimir Godár’s Concerto Grosso and so was able in my review to refer to the Slovakian composer’s “tortured channeling of J.S. Bach themes.” (I will, I promise, not complain again about high-flown program notes short on information). The four men and four women of the cast are dressed alike in long skirts, and the choreography maintains a tension between formality (regal manners, bows, male-female pairs, grand right-and-lefts, linear formations akin to those of a reel) and uncomfortable dissonant tangles. Partners take turns weaving through patterns or moving in well-regulated unison, but also show their differences. The lighting suddenly gets a bit wild. No one is happy at this party; they’ve all brought their troubles with them, and one pair’s final embrace in silence is equivocal.

The four terrifically adept men of Monte’s company (Alrick Thomas, Thomas Varvaro, Wade Watson, and Scott Willits) appear again in Rea-Fisher’s 1:3:4:1 (the working title of a premiere). To music by Paul Ukena, in lighting by Michael Cole, they enter alone or paired, as if this were an arena or a gym that fosters creativity. Whether in the air or slightly animalistic on the floor, they have the air of guys trying out demanding stuff. When they’re done, that’s it.

The Spotted Owl is billed as a “chamber version” of Muller’s 1995 work, and Marty Beller has edited his original score for it. The credits for this reconstruction take up almost half a page in the program. The work is indeed a rich one, in which spoken text by the dancers—which includes additional words by fourteen others (including Al Gore)— emerges from storms of dancing and transactions with the red “leaves” that all but cover the stage. A woman costumed somewhat like a peasant in Millet painting (Anna Levy) rakes up these paper objects and collects them in a basket; at one point, dancers line up to receive some of them. Intermittently marching on and off the stage, they handle the scraps as currency—seemingly counting the slips as they go, pocketing them or handing them to others in transactions that have no apparent results. Muller, you gradually realize, is skewering consumerism as well as bribes (once when the adroit performers call out their wishes, one person voices his/her deeply felt need for an electric garlic press).

If the work seems timely, it may be because the environmental depredations and immigration restrictions to which it alludes are coming to pass, and enormous amounts of money are influencing government policies that will make life harder for millions of people. Only a voice occasionally intoning “at the tone the time will be. . .” reminds us of an era when a phone call could get you information to set your clocks by.

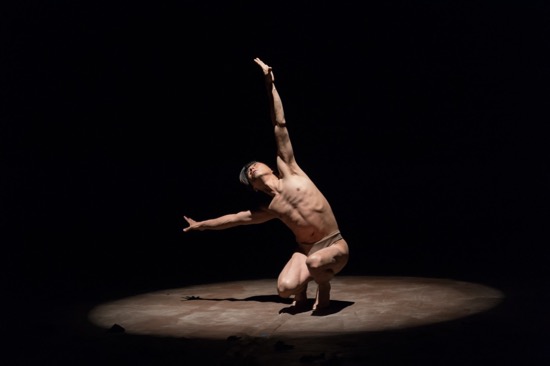

Gen Hashimoto in Jennifer Muller’s The Spotted Owl. Photo: Darial Sneed

Muller’s targets shift with sometimes dizzying speed. The remarkable solo performed at the outset by Gen Hashimoto, trapped in a circle of light, suggests that he could, like the spotted owl or the bald eagle, be a member of a disappearing species. He balances on one leg, twists his shoulders jerkily, throws himself into suspended turns, jumps into the air. Is he, in fact, trapped in an ecological disaster? All the cast members (Alexandre Balmain, Sonja Chung, Seiko Fujita, Hashimoto, Elise King, Elijah Laurant, Michelle Tara Lynch, Shiho Tanaka) hurl themselves into motion, lashing their arms and legs around as if they’re caught in violent storms, whether external or internal.

The dance as a whole envelops us in its own kind of storm, with the dancers brutalizing one another or something beyond themselves. They lecture us, harangue us with facts, nudge us into laughter. Ideas tumble around our heads, occasionally making crash landings. “I am an American artist,” announces one of the women of Asian ancestry, just before the end. The dancers start shedding excess clothes as they exit.

Ahmaud Culver and Megumi Eda in Karole Armitage’s Wall. On floor at back: Izabella Szylinska. Photo: Darial Sneed

When Karole Armitage left Merce Cunningham’s company, she went through a period when her own classical background and his movement-alone focus butted their way into a punk sensibility. Some of that obstreperousness remains, although her works are startlingly variegated. To this program, she contributed a preview of the first part of Wall, a work that is to premiere on July 1 at the Ravello Festival in Italy, plus excerpts from her marvelous 2007 Ligetti Essays.

The new piece is set to music by David Lang, a co-founder of Bang on a Can. Clifton Taylor provided the lighting, and Alba Clemente and Peter Speliopoulous designed the costumes. One of the things I admire about Armitage’s choreography is its rhythmic and dynamic variety. Quite a lot of what I see onstage these days maintains a constant sense of flow, with the movements borne on rippling, rolling tides. Wall is more like the kind of conversations we have—sudden exclamations, outpourings, pauses, and quiet interjections. Having said that, I must qualify it immediately, since some of the moves that Armitage designs stretch the dancers’ bodies to the limit, and there’s nothing everyday about her visions. For instance, early in the dance, Izabela Szylinski, who has been dancing on pointe with Ahmaud Culver and Megumi Eda, works her way upstage, falls, and lies down for a while. Alone with Culver, Eda opens her mouth in a silent yell and bites his hand, while he continues to support her coolly and watchfully. You see them struggle, but have no idea what they want.

These are not the only strange occurrences. In front of a brick pattern projected on the wall, another splendid dancer, Cristian Laverde-Koenig enters slowly, in company with a curious personage who’s wearing a kilt, the top part of which completely covers his/her face. Eventually this creature falls to hands and knees, while Laverde-Koenig and Szylinski dance again with Eda. Eventually the mystery person stands and the fallen hood is adjusted for maximum concealment.

Let me re-qualify my earlier remark. There’s nothing everyday about the amazingly extended and coiled-in and knocked-off-balance dancing, but it is performed as if it were a natural, acceptable way of behaving.

When I wrote about Armitage’s entire Ligeti Essays in 2006, I said that the dancing made me think of thin ice—“not just because it can be risky, but because it often seems on the verge of thawing. Its shifts are as piercing as those in the music.” I stand by that. Györgu Ligeti’s songs help create a climate of daring and uncertainty. Yusaku Komori and Emily Wagner join the four who performed Wall, and the cast’s strange, beautiful, awkward juxtapositions occasionally find refuge in the formality of two trios. This is a world in flux. I’m sorry that the bare white tree that figured in David Salle’s design for the piece doesn’t appear, but Taylor’s lighting enhances the choeography’s cool tempests.

Ligeti Essays ended a thought-provoking program that wasn’t as long in actual time as it seemed to be, due to the five individual views of dance and its mission. My compliments to the crew charged with changing gels on the sidelights between almost every piece. Their speed and accuracy rivaled, in a modest way, the excellent performing featured on this summer-evening profusion of dance.

Deborah, Thank you for writing about this project and these artists!

A program I very much would like to have seen and as usual the writing about it prompts much of that desire. Armitage was in Houston a couple of years ago and she appeared lively and spry.

I agree with “Quite a lot of what I see onstage these days maintains a constant sense of flow, with the movements borne on rippling, rolling tides. ” I see a lot of it myself and wonder where form has gone. Also I am curious about this remark: “a thought-provoking program that wasn’t as long in actual time as it seemed to be,” Keep informing us and we will keep reading.