The Mark Morris Dance Group celebrates the centennial of composer Lou Harrison’s birth.

Mark Morris dancers in Morris’s Numerator. (L to R): Noah Vinson, Sam Black, and Brandon Rudolph. Photo: Christopher Duggan

In 1991, the composer Lou Harrison wrote a piece for gamelan and harp and called it In Honor of the Divine Mr. Handel. On June 28, 2017, in Tanglewood’s Seiji Ozawa Hall, the Mark Morris Dance Group premiered a work, Numerator, set to Harrison’s Varied Trio for violin, piano,and percussion. The title of the program? Lou 100: In Honor of the Divine Mr. Harrison. That brings to seven the number of works that Morris has set to music by a man he considered a friend. Harrison, who died in 2003, didn’t attend.

The occasion was just one of several—most of them in far-west states—celebrating the work of this adventurous America composer, who learned from Henry Cowell and Arnold Schoenberg and, on occasion teamed up with John Cage. On May 14 (the day of his birth in 1917), admirers walked through the desert landscape of Joshua Tree National Park to attend Lou at 100: A Global Day of Art and Conversation. The musical celebration in his high-ceilinged former home (adobe encasing piled-up hay bales) lasted 24 hours.

Harrison’s musical tastes were far-ranging; he explored the instruments and the styles of Asia, early Europe, and elsewhere. He and his partner, William Colvig, built several large gamelans. Some of the five sections of the Varied Trio that inform and accompany Morris’s Numerator give a clue to the composer’s ways of mingling cultures. “Gending” refers to an Asian instrument and to a dry Javanese wind and was played in Ozawa Hall by Xiaofan Liu (New Fromm Player at Tanglewood) on the violin. With his sticks, percussionist Nick Sakakeeny struck delicate, ringing tones from an instrument that I couldn’t see clearly; the title of the section is “Bowl Bells.” Piano (played by Michael James Smith) and violin sing together in “Rondeau, in honor of Fragonard.” (On these two evenings, all but one of the musicians are Fellows of the Tanglewood Music Center.)

It’s always a pleasure to consider what Morris might have heard in a given piece of music that caused him to make his choreographic choices. What in Harrison’s Varied Trio for violin, piano, and percussion, for instance, made him want to set a dance for six men to it? (Or did he want to make a dance for six men and searched Harrison’s oeuvre for something that suited?)

The title, Numerator, is thought-provoking as well. Perhaps it stands for the six, who as denominators, can break their formations into twos and threes or six and one.

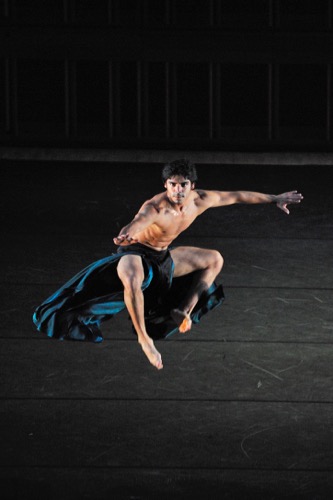

Mark Morris’s Numerator: Noah Vinson leaping, Sam Black sitting. Photo: Christopher Duggan

When the dance begins and the violin emits its quiet, windy melody, and the percussion is light, you can just make out a man lying on his belly. He begins to crawl along a diagonal; the other five men feed, one, by one, into that procession, cross the stage, and exit. As each man proceeds, his stance gradually moves to an upright posture, and Nick Kolin’s lighting gradually brightens. If you can envision this prelude, you may be tickled to see it as I did: an illustration of the human race moving from its amphibious beginnings through reptilian and simian evolutions to “man.”

These are the men: Sam Black, Domingo Estrada, Jr. Aaron Loux, Dallas McMurray, Brandon Randolph, Noah Vinson. They wear black pants and bright-colored, short-sleeved, loose-fitting shirts designed by Elizabeth Kurtzman. The shirts, flowing as the men rush or spin, make me think of hot-climate, island attire. All but Black return to the stage; circling and weaving, playing a kind of peaceful tag without the drama or role-playing of a real game.

Black re-enters alone, and the others do so lined up, their backs to the audience, each with an arm around the next man. When they break apart, it’s to balance on one leg, while Black runs around them, then backs between two of them to devolve on the floor.

Not all is gentle and friendly in Numerator; the dancers roister in unison, and their drooping downward becomes an occasional motif in “Elegy,” as does their scrabbling on the floor. “Rondeau,” alludes to the medieval poetic and musical form with a cycle of changing partners. After Estrada and McMurray have danced together—sweet-tempered, holding hands, arms around each other—Estrada exits, and McMurray dances with Vinson; then McMurray, having had his turn, goes away, so Vinson dances with Black; then Loux ushers Vinson offstage so that he, Loux, can pair up with Black; after which, Randolph replaces Black and dances with Loux. Finally, bright sidelights, light drums, and plucked strings require the six to divide themselves into pairs, then into threesomes, then, paired again, to hug. Three times two is six, two times three is six, and the wonderfully dancing denominators call it a day.

Laurel Lynch (L) and Aaron Loux in Mark Morris’s Pacific. Photo: Hilary Schwab

The other three works to music by Harrison on the Tanglewood program are older. The marvelous Grand Duo dates from 1993; Morris created Pacific for the San Francisco Ballet in 1995; and he built a solo, Serenade, in 2003. Pacific, the program’s opener, is set to the third and fourth movements of Harrison’s Trio for violin, cello, and piano. When I first saw the MMDG perform it, I was struck with how much more fluid its balletic steps looked when executed by Morris’s dancers. Their legs fly up, they spin as if suspended, they leap as if blown upward. In this they are enhanced by James F. Ingalls’ lighting and costumes by the late Martin Pakledinaz. Both men and women wear long, full white skirts, splashed with colored designs; the men are bare-chested, the design on the women’s skirts continues upward onto their bodices.

An earlier cast in Pacific. (L to R): Chelsea Acree, Lesley Garrison, Stacy Martorana, and Laurel Lynch. Photo: Hilary Schwab

The music—played by Liu (violin), Francesca McNeeley (cello—another New Fromm Player) and Smith (piano)—is assertive at first, with heavy chords on the piano, but full of variety. Perhaps because Morris made the work for a ballet company, he often presents four of the women in green-streaked costumes (Rita Donahue, Lesley Garrison, Laurel Lynch, and Nicole Sabella) as a unit. That’s often true of their blue-marked men (Estrada, Loux, and McMurray). Vinson and Sarah Haarman, who perform a nice duet with lifts, wear ones splashed with orange. The foam-up of the skirts hint at breaking sea waves, the pauses suggest cresting ones, and the dancers’ rushing in and out of formations conjures up balmy breezes. (Maybe my own California seaside youth and the driving quality of some musical passages are responsible for this reaction.)

As is often the case in Morris’s choreography, small precise gestures contrast with the organized swooping and vaulting. At several points, the dancers cup their hands near their chins and then cross them in front of their chests. And many times they stop, poised on the balls of their feet, reaching one arm straight up and gazing down on the opposite side.

Lesley Garrison in Mark Morris’s Serenade. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Initially, Morris choreographed Serenade to Harrison’s Serenade for Guitar as a solo for himself. In this quirky, quite charming little variety show, he also played the finger cymbals and the castanets called for in two of the score’s five sections. Garrison, wearing Isaac Mizrahi’s long black skirt and severely cut white top with two little fantails at the back, manages the cymbals’ quick punctuation in “Usul,” but Morris slips onstage to provide castanet rolls for the final “Sonata” section, joining a guest musician, guitarist Robert Beliníc, and Marcelina Suchocka, who strikes the rims of two different-sized red drums, strokes their centers, and occasionally makes a large cymbal resonate. Garrison has grown into Serenade since last fall, whether she’s dancing seated on a black box; shaping herself into two-dimensional designs while manipulating a thick, glinting metal rod (off which Michael Chybowski’s lighting bounces); flipping a fan open and shut with staccato precision; swinging her hips while making the finger cymbals ring; or flying around the stage while Morris goads her with the castanets. Garrison refrains from flirting with us; the routine is a series of demanding tasks, and she wants to finish them in style.

The Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris’s Grand Duo. Photo: Erin Baiano

The evening ends with Grand Duo, one of my favorite Morris works. It is in four sections and requires 14 dancers, among them Mica Bernas, Durell R. Comedy, Brian Lawson, and Billy Smith, who haven’t yet performed tonight. Samantha Bennett (New Fromm Player) is the violinist, and Nathan Ben-Yehuda plays the piano. One section of the music is titled “Stampede,” and that’s not the only section in which movement and music seem to be thundering across a limited-space prairie, sometimes jolting you pleasurably with its syncopations.

Morris starts out with a mystery. These people, wearing Susan Ruddie’s costumes (satin dresses, kilts, tunics, and variations thereof, have perhaps gathered for a ritual. When they lift their hands high, those hands enter a horizontal beam of light that Chybowski has hitherto concealed. Interestingly, because uncommon in Morris choreography, there are a few moments when all the dancers know a common phrase of dancing and perform it in different timings. When they pair up, each couple has its own sequence.

As the music sometimes stutters, so do their feet, spread wide apart beneath bent knees. There are other curious moves. In one, they’re lying on their stomachs, but rear up to brace their weight on their hands; then, responding to something in the music, they jut their chins forward. The women’s loose hair flies. Individual moments and encounters seethe up in the pressing-forward music—not that there aren’t slow passages, spare ones, and singing ones in Harrison’s splendid score.

Domingo Estrada, Jr. in Mark Morris’s Grand Duo. Photo: Katsuoshi Tanaka

In the last section, during Harrison and Morris’s exhilarating, terrifying, invigorating “Polka,” the dancers sit in a circle and nod or shake their heads, but calm moments are rare. They have now changed costumes or shucked part of what they were wearing. Lord, how they hunker down, their feet pounding the floor; their legs flicking and kicking out! How they twist and shake and punish the air with their fists! They dance in a circle, split into two fast-moving, nestling curves, and resolve it again. And they are precise in their strength, immaculately so. Harrison’s music is a bucking bronco, and they’ve gripped it tightly. If this were Rite of Spring, someone would have to die. Not in this tribe of Morris’s, for sure.

I love this review, Deborah. Thank you so much. The Morris company is coming to Portland next season, but they’re not doing this show, alas. Nevertheless, through your eyes, I feel I have seen it, for which I am profoundly grateful.