A production of From the Horse’s Mouth celebrates Indian dance at New York’s 14th Street Y.

Prerona Bhuyan (L) and Madhushmita Bora costumed for From the Horse’s Mouth

Next year, From the Horse’s Mouth will celebrate its twentieth anniversary. Since its debut at the Joyce Soho, over a thousand people connected with dance (twenty or more at a time) have performed in this peripatetic structured improvisation, conceived and directed by Tina Croll and Jamie Cunningham. Appearing in those first performances, I remember the delight of canoodling backstage among a highly diverse population of dance people and the amazing onstage spectacle of Viola Farber and Carmen De Lavallade improvising gently together (imagine their artistic parents, Merce Cunningham and Lester Horton, getting along this well).

I’ve since seen or participated in diverse iterations of the work, but never one quite like the one at the 14th Street Y celebrating Indian Dance in America and curated by Rajika Puri. The structure is always pretty much the same. Each performer arrives having prepared a short anecdote, a 16-count phrase of movement in place, and a travelling phrase. Onstage, they pick up cards that instruct them how to vary the phrase in place and the path to follow on the travelling one. There are usually four people onstage at a time, the fourth being at liberty to improvise and to interfere with the others if he/she so wishes. These are periodically interrupted by diagonal parades of performers wearing their favorite costumes (rather than the red and black outfits that they wear in their Part A appearances).

From the Horse’s Mouth dancers on parade. Photo: Adam Macks

This process is possibly not something that expert dancers in the various traditional styles of India have engaged in before. Nor is the contrast between styles as intense as, say, one between a principal dancer in a ballet company and a person skilled in martial arts, but nevertheless, accommodation and investigation are part of the pleasure. Also, even today, many dancers schooled in classical Indian traditions (Kathak, Bharata Natyam, Odissi, Kuchipudi, Mohiniyattam, Sattriya, etc.) perform as soloists. So it’s especially moving (and entertaining) to see them enjoying interacting with one another.

The performances on East 14th Street are dedicated to the memory of the great Balasaraswati. Kamala Cesar, who studied with her in India for over a decade, recalls for us her initial shock when “Bala” commanded her to execute a sequence of stamping 150 times and left the room for a while; by the time she returned, her student’s anger, pain, and fatigue had vanished into transcendence. Balasaraswati’s image appears among the photos intermittently projected onto the backdrop. These hint at the legacy of Indian dance in the U.S.: Ted Shawn appearing as Shiva, Ruth St, Denis, Anna Pavlova in an “oriental” number with Uday Shankar, Ram Gopal. Ragini Devi and her daughter, Indrani, are also seen, and Indrani’s daughter, Sukanya, speaks of the family tradition in a projected video .

Donia Salem (L) and Shruthi Mohan in From the Horse’s Mouth. Photo: Adria Rolnik

On the night I attended, twenty-nine people performed, but there are thirty-five listed on the program, so each show may vary. Seldom has the 14th Street Y’s black-box theater heard so much rhythmic stamping or seen so many precise gestures, flashing fingers and eyes, and such a variety of shimmering silk costumes and jewelry. And here’s something not typical of From the Horse’s Mouth performances: all the performers speak with animated clarity, as if they’d been constructing and perfecting the delivery of their stories for weeks. Whether born in America, India, or elsewhere, these artists tell of inspiration, of lessons learned from gurus, of turning points in their lives. For Joe Daly, the influential words of wisdom were, “Never teach what you already know.” For Sonali Skandan, an early moment of happiness came at the age of 5, when, new to America, she made a friend in school. Madhusmita Bora recalled preparing to play the child Krishna when she was a little girl, but was ordered to leave the temple because her father had been ostracized; she decided she would never dance again. Donia Salem, a poet as well as an Odissi dancer, delivered with fierce intensity a poem that tells of a dark period in her life and how she danced that darkness out of herself, while Carol Mullins’ lighting throws her shadow on the floor. Anita Ratnam was told “girls don’t dance.” Want to bet? Politics and visa problems and gender issues (the boldly transgressive Hari Krishnan on video) crop up too. Seated on the chair that every speaker uses, Puri gives a bravura performance as she recounts the legend of Sati, in love with Shiva and snubbed by her father, Daksha. Seeing Puri as Sati turn into Kali, the goddess of destruction, is a terrifying experience. These are just a few of the twenty stories, told the night I attended by dancers, choreographers, teachers, and company directors, three of them on video (Surupa Sen of Nrityagram, wearing a beautiful river of red fabric, speaks of her guru, while seated on a rock in a forest and accompanied by birdsong.)

Almost all the speakers go through all three stages of Part A, although Shobana Ram drops out to sing or chant wonderfully for her colleagues. Eight fine additional performers do not speak, but perform the other duties involved in Parts A, as well as parading in their finery for Parts B.

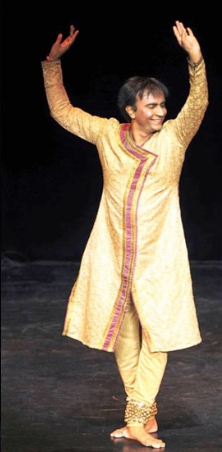

Prashant Shah, Kathak dancer, who appeared in From the Horse’s Mouth

Your eyes travel around the stage—now riveted on the speaker, now arrested by something fascinating going on somewhere else. How not to look at strong Bharata Natyam dancer Jeeno Joseph (he’s also working on his doctorate in Physical Therapy)? At Prashant Shah with his wonderfully sensuous strength (he dances as if melting into the movements). At Aishwara Madhav in a pool of light, holding an invisible mirror as she beautifies herself (no doubt for a rendezvous with the god Krishna). The collaborations that crop up may result in sensitive unison or hint at helpful relationships. I catch Joseph again, joining (as I recollect) Kathak dancer Jin Won and Bharata Natyam exponent Sophia Salingaros, while they, kneeling, mime playfully splashing water on him from an invisible pool. Sisters-in-law, Bora and Prerona Bhuyan work as a team, costumed similarly, stepping in unison.

Most of these performers have devoted years to strictly defined traditions, sometimes more than one, not all of them Indian. But they have also been willing in these performances to dance themselves into artistic comradeship with one another. And that is heartening to see.

Pioneers of Indian dance in America