The Limón Dance Company performs at the Joyce Theater, May 2 through 7.

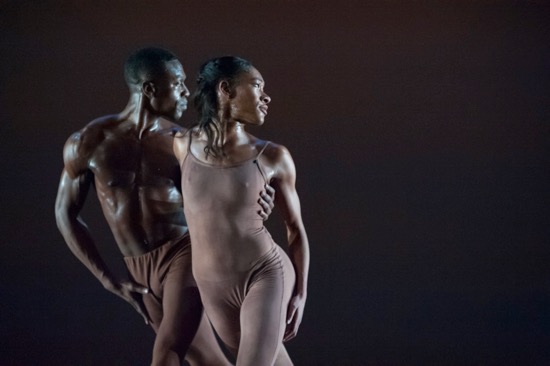

Members of the Limón Dance Company (L to R): Elise Drew Leon, Jesse Obremski, and Kathryn Alter in José Limón’s Concerto Grosso

José Limón might have been a fine architect had he chosen that profession instead of dance. Beginning his career in the company led by Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman, he inherited some of their principles of movement and, shortly, a mentor: Humphrey herself. And during the latter part of his career, when he had a large company to work with, he created moving walls and tides and chains of dancers.

During its season at the Joyce, the Limón Dance Company, directed since last July by onetime company member Colin Connor, showed the lyrical aspect of Limón’s work, a well as the architectural and the dramatic—contrasting these with Connor’s own Corvidae and Kate Weare’s Night Light.

Limón choreographed Concerto Grosso in 1945. There was no room for a large ensemble in Humphrey and Weidman’s studio theater on 16th Street, and only three dancers were needed for the work he set to Antonio Vivaldi’s Concerto #11 in D minor. Humphrey based her style on a fact-of-life duality: falling and recovering—not always literally falling to the ground, but aware of the pull of gravity, even when not compliant with it. The dancers step out into a movement and suspend it a second before falling into the next step. You can absorb this as exaltation or a teasing delay of the inevitable.

At the Joyce performance that I saw, Kathryn Alter, Elise Drew Leon, and Jesse Obremski performed with precision and spirit a production of Concerto Grosso staged and directed by Risa Steinberg. It’s a formal trio, an elegant but carefree playground; the three often dance in unison, facing the audience, but the man has two partners to relate to—ready to help them up if they’ve swirled to the ground. (For me, the pleasures of the choreography were somewhat compromised by the extremely high volume at which the recorded music was played).

The architectural skills that Humphrey may have fostered in Limón are evident in a suite drawn from his long, rich A Choreographic Offering (set to J.S. Bach’s A Musical Offering and staged and directed by Kurt Douglas). Humphrey died of cancer in December 1958, and Limón constructed this dance as a memorial in 1964, drawing on sequences from her dances. It’s as if he had unrolled a long carpet of changing designs. The performers rush into group patterns and out again, exhilarated; they find partners; they wander dreamily; they pause, balanced on one leg; they fall to the floor and rise again. And, lord, how they fly! That is, leap, hop, skip, jump and perform many variations of these, countered by suspended turns. A trio for three men (Obremski, Ross Katen, and David Glista) opens the work. Obremski and Drew Leon lead the second section, and Alter and Katen perform an allegro duet with wonderful wit and pleasure in each other’s company.

Mark Willis and Kristen Foote in José Limón’s The Exiles. Photo: K Chang

The Exiles (1950), staged and directed by Connor, is another matter: a duet for Adam and Eve (or any pair with similar challenges). Kristen Foote and Mark Willis give whole-hearted, dramatic performances. Limón chose the moment just after the pair are driven from the Garden of Eden and must cope with a new world. He set his work to Arnold Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No. 2, Opus 38, and we hear a stretch of it before the curtain rises. The unfortunate two run in, their arms around each other—as closely linked as they are in Renaissance paintings of the post-apple-eating crisis. Their unitards (designed by Limón’s wife Pauline Lawrence) match their skin color so exactly that they appear almost naked. Shame plays a large part in this Christian vision. The two often crouch over, wrapping their arms around themselves to hide the private parts they used not to notice. But this is a dance of discovery. The earth is not so bad after all.

Limón had some ingenious ideas. They discover slender blue ribbons lying on the ground, and with adroit twists and turns present themselves as “clothed” even though their bodies are still fully visible. They come together in awkwardly tender ways. Willis hinges backward at the knees, catching his weight on his hands; Foote falls back across him, then kneels on his thighs.

But when the music changes, and the backcloth glows blue (everything looks better the next day), they cast off the ribbons and become playful. They still look up at times or cringe, but she also dives onto him and convulses. They swing their legs in opposite directions; which way to go? They exit taking big steps sideways—now looking back at what they lost, now looking toward the life that lies ahead.

I wasn’t able to attend one of the performances at which The Exiles was performed in different costumes by Chris Hynds, with new lighting by Christopher Chambers, and a new score by Aleksandra Vrebalov that involves six singers. Any questions I might have about the rationale for this new version remain, for the time being, hovering in my mind.

Colin Connor’s Corvidae (members of both casts). Limón dancers (L to R): Kathryn Alter, Kristen Foote (mostly hidden), Logan Frances Kruger, Ross Katen (partly hidden), David Glista, Jesse Obremski (partly hidden), Bradley Beakes, Alex McBride. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Connor’s Corvidae (2016) is set to the first movement of Philip Glass’s Violin Concerto #1, although it starts in silence, with the six black-clad dancers entering gradually, beginning with Glista. The title refers to the family that includes ravens, crows, and blue jays—smart, loudmouthed fellows and, in the case of some of them, fond of gatherings. Clad in diverse black outfits, Bradley Beakes, Leon Cobb, Logan Frances Kruger, Glista, Katen, and Savannah Spratt flock, rush about, and pause to check the territory. A group may gain followers as it travels. Individuals (Cobb for one) are briefly foregrounded, then enter the group or are absorbed by it. These people are tough—sometimes suspicious, sometimes wary. One compositional strategy would have been foreign to Limón: Near the beginning of Corvidae, they scatter into a very loose canon, foraging individually; your eyes can’t absorb them in an orderly fashion, just as you might view a murmuration of starlings.

Logan Frances Kruger and Leon Cobb in Kate Weare’s Night Light. Photo: Christopher Duggan

I’m sorry I missed seeing Kate Weare’s Night Light when second-year Juilliard students premiered it during the dance department’s New Dances: Edition 2014. There were probably more dancers than the dozen than the Limón company can muster. It’s fascinating nevertheless. The two selections of music have more in common than you’d think, considering that they were composed over three hundred years apart. “A Song for Mick Kelly” from Victoire’s 2010 album, Cathedral City, and the Passacaglia for unaccompanied violin that ends Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber’s The Rosary Sonatas link through the implications of the their titles, as well as by the prominence of a solo violin in part of the former.

The fine lighting, designed by Clifton Taylor and executed by Chambers, and the costumes by Fritz Masten heighten the atmosphere that Weare has created. Men and women alike wear short, long-sleeved, very full shirts in shades of blue. When they spin—and they do a lot of spinning—the outfits flare out around them. After a while, some of them appear without the shirts, wearing only black trunks (plus bras for the women). The casting off of garments has some significance I can’t understand for sure.

This resonant work, too, makes me think of architecture at times, but of a structure that is only intermittently stable. One of many things that interest me about it is the undercurrent of aggressive force that seems to be accepted. Kruger and Cobb enter from opposite sides of the stage, meet, and explode. She recoils, as if pushed, yet leans in to lay her head briefly against his chest and then cover his mouth with her hand. The others, often forming lines—single ones either side of the stage, doubled on one side, or along diagonals—also reprise that image of people pushing or being pushed from the group. It’s as if this society can’t at times exceed a given head count.

Jesse Obremski (L) and Mark Willis of the Limón Dance Company in Kate Weare’s Night Light. Photo: Christopher Duggan

At one point, you can hear voices, buried in grinding sounds, attempting to surge up. The dancers jump as if coming down heavily were their task. Then silence, and the music turns soft and hoarse. There are strange, temperamental movements here and there: people open their mouths and partly cover them with their fingers; they shiver; two of them appear to lift their partners by the scruff of the neck. When not dancing, they sometimes stand and watch others. There’s a fierce struggle between Obremski and Beakes. And when I say “dancing,” only occasionally do I mean staying put and moving in complex ways. The dancers often rush past, hunkered down over their space-covering steps. I begin to think of them as a community dealing with its members’ individual outbursts, their joint plans, and their reporting for duty. But mystery is a part of it. What is that “night light?” Does it shine down on them, or make their path difficult to see?

The Limón company dancers look terrific, committed to making accuracy seem like a full-bodied necessity of life.