Tamar Rogoff’s Grand Rounds at La MaMa, April 27 through May 14.

Tamar Rogoff’s “family” in Grand Rounds. (L to R): Morgan Sullivan, Emily Pope, Cyndy Gilbertson, Cadence Rotarius, Glen Heroy, and Jake Szczypek. Photo: Theo Cote

Choreographer Tamar Rogoff grew up in the 1950s reading Helen Wells’ mystery novels about a nurse named Cherry Ames, who’d risk the wrath of the doctors she served by resourcefully breaking the rules in order to save a patient’s life, if no one else was around. From Cherry Ames, Student Nurse (1943), Nurse Ames went on being brave through World War II (Cherry Ames, Army Nurse, and Cherry Ames Fight Nurse) and the Korean War up to 1968. I don’t know if Rogoff read all twenty-seven books (including some by another writer), but the first one plays a crucial element in her fascinating new work, Grand Rounds.

Solving mysteries is just one ingredient of the Cherry Ames books. More time is given to how the heroine deals with hospital life and its own near disasters. Rogoff has created another kind of mystery by interweaving elements of the chosen book with visions of a family’s life (some of these relating to her own growing up). The link between the two worlds is provided by 10-year-old Cadence Rotarius, who is part of the family and the one who is reading (sometimes on tape) the book she clutches: Cherry Ames, Student Nurse.

As is often the case in a work by Rogoff, the performers are distinctive. Gray-bearded actor Glen Heroy (Grandfather) was a Big Apple Circus clown. Cyndy Gilbertson (Grandmother) has been dancing with Parkinson disease for 29 years. Peter Selwyn (Dr. Wiley) is himself a doctor and and author. Actor Morgan Sullivan (Brother) is a transgender advocate. Almost everyone in the cast wears several hats in terms of careers and interests.

On a bed in Grand Rounds: Cadence Rotarius. On platform (L to R): Nitzan Mager, Graham Bridgeman, Aurelia Suchilt, Peter Selwyn, and Berenice Suchilt. Photo: Theo Cote

La MaMa’s Ellen Stewart Theater was reconfigured for Grand Rounds. The “hospital” scenes take place on the risers where the audience usually sits: the lone patient (I saw Aurelia Suchilt in the role) has a bed up there. The empty risers become hospital corridors and on the highest level, a blue curtain masks all but the lower legs of those in an operating room. The little girl’s bed is placed below the risers, and three more beds sit in a tight circle in the middle of the open space. We spectators either sit on chairs or—even closer—on boxes ringing each bed.

A piece Rogoff presented at P.S. 122 maybe twenty years ago also featured vignettes on beds; in that case, the performers repeated their dances several times, and the audience travelled around to visit them. In this first part of Grand Rounds, we stay put, and the performers—presenting each act three times—move from bed to bed, smoothing or altering the bedclothes when they enter a new “room.” The heads of the identical beds are barred horizontally and provide spaces to reach through or be pulled through, or to stand atop and contemplate the terrain.

The relationship between Gilbertson and Heroy is a tender one. She is restless, changeable; he is sometimes worried, sometimes soothing. She can stand on the bed, leaning out like a ship’s figurehead; he, lying on his side, can be a place for her to sit. When he lies athwart the mattress, she decides to roll him back and forth. The partnership that Emily Pope (Mother) and Jake Szczypek (Father) have forged also has a degree of tenderness, but they fight a lot. He raises a hand; she grabs his arm and stops the gesture almost before we know what it is. Stroking the other person’s cheek may instantly turn into a harsh tackle. These two performers are dancer-athletes, their moves on the bed as swift, complex, and punitive as those of Olympic contenders, but tempered by unspoken questions and temporary truces.

Cadence Rotarius and Jake Szczypek look up at Emily Pope. Photo: Theo Cote

The little girl visits these scenes as an observer, but spends more time with her much older brother. He has problems, perhaps because of what lies ahead; he (we will learn) is to be a soldier. He braces himself on the headboard and stares into the distance, gets under the foot of the bed and tips it up many times for weight training. But he also snuggles with his sister, crosses four fingers to tempt her to “put your finger in the crow’s nest, and looks at the Cherry Ames book with her,

All the time, we hear relevant snatches of music, voices, static, crackling radio commands, excerpts from the book (sound design and original music by Steve Brush). During transitions among beds, when Joe Levasseur darkens the area where we’re sitting, we watch encounters between nurses and doctors and their patients up on the risers. No, the patient cannot just walk away from her IV drip. Oh-oh, the student nurse shouldn’t have left that bag for a doctor to trip over. The two nurses (Nitzan Mager as Cherry Ames, Berenice Suchilt as her colleague Vivian Warren) consult charts, giggle, hustle to keep up, and accept rebukes from Dr. Wiley (Peter Selwyn) and help from Dr. Jim Clayton (Graham Bridgeman); the clever use of a stethoscope tells us that the hearts of Nurse Cherry and Dr. Jim beat rapidly when they’re together. We learn more about the hospital personnel as the beds and boxes are moved away, and spectators find new seats. These members of the medical profession are not above forming kick lines (at least, perhaps, in the Child’s dreams) or playing “pass the bedpan.”

I’m providing the names of these characters from the Cherry Ames book because I’ve read them in the program. But I can’t always grasp the relationships or the histories as I watch and listen. I hear the words “he joined the army,” I hear a list of airplanes of the Korean War era. A relevant World Series is mentioned, so are prisoners. “Mr. Sandman,” which we hear sung, dates from the 1950s.

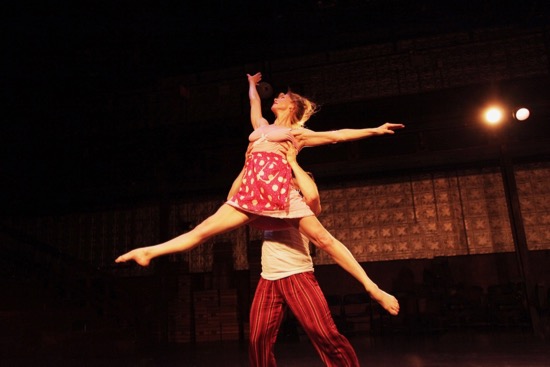

Jake Szczypek lifts Emily Pope in Tamar Rogoff’s Grand Rounds. Photo: Theo Cote

The second part of Grand Rounds puzzles me at times, but also enthralls me. Pope and Szczypek perform a balletic pas de deux, with soaring lifts to music by Invert. (They also reprise their antagonism, fighting over the book their daughter is reading, while the others watch.) Hats and other items are handed out and induce role-playing (Gilbertson briefly acquires a beret and a cigarette and the manner to go with them).

One section in particular makes me uncertain as to what Rogoff is telling us; it seems almost extraneous. The performers (mostly Rotarius and Sullivan) rapidly construct a wall out of the boxes. The three females of the family move in unison on one side of the wall; the males on the other. Then they reverse sides so we can take in both, and each time, one person, angry, makes a breach in the wall.

Near the end, in a very resonant passage, the family members form several tableaux. In the final one, Sullivan is supine, with the others staring down at him. They’re still staring at that spot when he slips out of it and, guided by Rotarius and her flashlight, he mounts the risers, is garbed in a hospital gown, and escorted into the curtained “room.” Is an operation in progress, or is this a final visit? Surgical masks are fitted onto the visiting relatives, one by one, and they all crowd in behind the curtain. Their parade brings to mind the images of a medieval dance of death.

Cadence Rotarius gets a dance lesson from Nitzan Mager. Photo: Theo Cote

I want to say “Stop! “Tell me what happened. What went wrong for that boy?” The boxes, set out in two rows while our gaze was on the risers, reveal gravestones painted on their sides; a performer sits by each one. Rotarius and Sullivan walk haltingly along a path of light toward the end of the space opposite the risers; he lets her lead, but they also walk side by side for a while. She seems about to follow him into the inevitable darkness, but is stopped by Mager, whose Cherry Ames uniform is now covered by the skirt of a tutu. She puts another tutu on Rotarius, who wears tap shoes. More music from Giselle. The nurse-ballerina then gently teaches this child, who surely stands for Rogoff, how to use her arms gracefully. We’ve been drawn, unsuspecting, into a tragedy and just as suddenly emerge from it.

Brother and sister (Morgan Sullivan and Cadence Rotarius) dance together, perhaps in a dream. Photo: Theo Cote

And yet, and yet. . .Sullivan returns garbed in his uniform. Was he fatally wounded in battle and returns to dance with his sister only as a bright memory? To music from Giselle, he sashays around her; she does a flip and dives into his arms. But then he hides behind a gravestone. Silence. Almost all the lights are off. Rotarius stands for a moment in first position. Then she mounts the risers to sit beside Mager, who crowns her with a nurse’s hat, welcoming her into the profession. Together, they open a book, while a recorded voice begins to read. I don’t need to tell you what book it is.

All the performers are marvelous at conveying the subtle emotional changes; they make you understand what they’re going through at every moment, even though Rogoff has threaded together so many complicated and witty and loving and heartbreaking images that it’s easy to lose your way in the piece. As I write my questions, I begin to sense some of the answers. The little girl with the golden hair is a guiding spirit, as well as an observer and a participant. These are events as she lived them and recalls them, and, in her dreams, also enters the book she is reading. That she receives her nurse’s cap is Rogoff’s way of letting us know that through all the joys and sorrows of her childhood, she will grow up and move on enriched.

A journey into darkness. Morgan Sullivan and Cadence Rotarius in Tamar Rogoff’s Grand Rounds. Photo: Theo Cote