Compagnie CNDC Angers – Robert Swinston bring three dances by Merce Cunningham to New York.

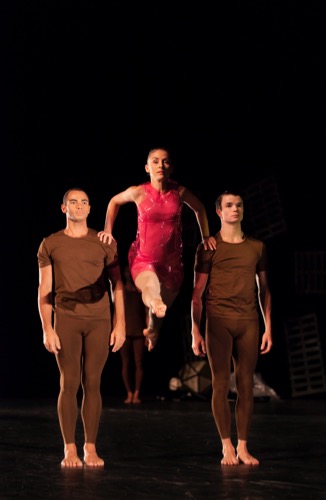

Merce Cunningham’s Place. CNDC Angers’ Anna Chirescu, lifted by Adrien Mornet (L) and Alexandre Tondolo (who did not appear at the Joyce). Photo: Charlotte Audureau

Merce Cunningham didn’t want us to try to find stories in his dances. We obeyed. But dance can hint at the essential stories that lie deep under narratives that deal with, say, characters falling in love with the wrong person or being transformed into swans. Cunningham presented us with quiet landscapes occasionally ruffled by wind, dark places where people collapsed or handled one another awkwardly, a playground for very wily adults. And more.

I brought up the above examples because the three Cunningham dances that Compagnie CNDC Angers – Robert Swinston presented at the Joyce Theater this week are Inlets 2, Place, and How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run. Swinston, who danced in the Cunningham company, assisted Cunningham during his last years, and directed the company during its final Legacy Tour (2010-2012) after the choreographer’s death, has chosen this program well. CNDC, based in France, in one of the country’s Centres Nationales de Danse Contemporaine, has a roster of only eight dancers, and the contrasting works named require that number or fewer. They are performed without intermission; only pauses give the dancers a chance to refresh themselves and the spectators an opportunity to talk.

Inlets 2 (1983) is a reconfiguration, by chance methods, of the sixty-four movements that made up Cunningham’s 1977 Inlets. It has seven dancers, rather than six, but is performed to John Cage’s original score. Cage and Cunningham met at Seattle’s Cornish School, when Cunningham was a student there and Cage was teaching, composing, and accompanying dance classes. Mark Lancaster’s blue backdrop, clear lighting, and costumes with a hint of shimmer don’t suggest a landscape in which crashing waves figure, but a backwater where light sparkles on calmer water.

Members of DNDC Angers – Robert Swinston in Merce Cunningham’s Inlets 2. (L to R): Carlo Schiavo, Flora Rogeboz, Adrien Mornet, Catarina Pernao, Anna Chirescu (partly hidden), Claire Seigle-Goujon, Lucas Viallefond.

Cage’s accompanying music reinforces that kind of lapping water in a very direct way, Gene Caprioglio, Arnold Hie, and Laura Kuhn stand behind a table on which sit their instruments; each has a huge conch shell and two smaller ones. The shells hold water, and tipping them in different rhythms creates a sense of the outdoors. At times, the musicians also blow into the shells: a hoarse, windy cry.

The choreography contrasts stillness with soaring. Alone, together, in twos or threes or fours, Anna Chirescu, Adrien Mornet, Catarina Pernao, Flora Rogeboz, Carlo Schiavo, Claire Seigle-Goujon, and Lucas Viallefond discover all sorts of ways of leaving the ground behind. They jump, leap, hop, vault from two feet to land on one and vice versa—all performed fully, but without a show of effort. Frequently, one or more stand still, moored and watchful, while others move, quick-footed, around them.

They stalk on tiptoe; they flock. You take notice of certain kinds of behavior, such as dancers crossing one leg over the other and hooking it there while sinking slightly. Or stroking one hand down one’s other arm—a formalized grooming. The men may dance at the same time, or the women, but no one handles anyone else. As with most Cunningham dances, your eyes may be caught by a movement erupting in a corner, before another activity or encounter draws your gaze elsewhere.

Merce Cunningham’s Place. CNDC Angers dancers (L to R): Claire Seigle-Goujon, Anna Chirescu, Gianni Joseph, and Lucas Viallefond. Photo: Charlotte Audureau

Place, the centerpiece of the program, offers no such peaceful vision. At the back of the stage, hang variously placed and tilted wood grills, some of them in disrepair; here and there a newspaper page dots them (Beverly Emmons designed these, plus the lighting and costumes, in 1966). The men wear earth-brown tops and tights; the women’s tinted, transparent plastic dresses glint erratically in the beams of light. At the back of the stage, two lamps (one small, one large—a little like Japanese lanterns) sit on the floor. Later, they will be lit.

Place is an early example of Cunningham casting himself as an outsider—but maybe not an outsider in the sense of an explorer confronting an alien culture; perhaps the teacher-choreographer testing ideas and trying out things with his dancers. Gianni Joseph in Cunningham’s role is alone onstage at the outset: watchful, preoccupied. He stands on one leg and holds the other bent one up close to him with both hands; the next minute—rapidly and smoothly, miraculously— he’s sitting; then he puts his hands on the floor, pushes himself up, and does it again. A second solo, a few minutes later, is even more intriguing; his hands are curled loosely into fists, and he flicks them around; after launching himself into a jump, he seems to be trying to discard his own arms.

In this dance, too, the stage picture is constantly changing, but there’s an aura of danger and disintegration. The music, Gordon Mumma’s Mesa, abets this. Mumma’a sound source was Cunningham musician David Tudor playing a bandoneon (a kind of concertina), which the composer then manipulated electronically (the process was a complex one). You might not hear the bandoneon (once I was sure I did) amid the composition’s array of sounds—some very loud and often eerily discordant.

A pool of light occasionally appears in the center of the stage, and at least twice, the performers congregate around it or rapidly circle its rim—suggesting a ritual that isn’t sustained. The eight of them handle one another a lot. Chirescu collapses, and Joseph catches her. At one point, three of the women (or maybe all four) are carried away, uncomfortably bundled up or held in other ways. Mornet enters with Rogeboz hanging from him upside down; he lowers her into a backbend and inserts himself into the arch that she’s creating. Then he picks her up again, arranges her as before, and starts to walk away with her. Just before he reaches the edge of the stage, Schiavo and Villefond take her off his hands.

Anna Chirescu and Gianni Joseph of CNDC Angers – Robert Swinston in Merce Cunningham’s Place. Photo: Charlotte Audureau

The women often seem without agency. Trios form; two men carry a woman high, then adjust as another man replaces one of them. But the duet (created for Cunningham and Carolyn Brown) has a tenderer, more companionable air. Chirescu and Joseph walk slowly together, he pressed close to her back. Together, they look skyward, as if expecting a change in the atmosphere. But they also perform over and over a passage in which he helps her to stand on one leg, then hold her while she crosses her lifted leg over and into a deep lunge; when she recovers (I forget just how), they begin again. The image created is of a laborious journey over a strangely uniform terrain. The music, which has been sounding like a buzz saw, suddenly falls silent.

The last part of the dance has other images that suggest looming danger and behavior that surfaces and dissipates. Joseph claps his hands (the leader signaling his followers, the choreographer demanding attention in a rehearsal, or just a sharp sound?). He plugs in the lamps, and then, bit by bit, pulls them stage left (they must be on a board). He sits and rests in between stints. The music builds, stops, starts again. Each time, in the silences, the some of the individuals in the cluster that’s moving slowly toward a downstage corner make periodic adjustments in relation to the others. When the four women suddenly lie prone on the floor, the men leap around them. These leaps aren’t separated by preparatory steps; the dancers spring into the air repeatedly, as if leaping were just another form of walking. It’s after this that the women recover and are carted off like bundles. Once he’s alone again, Joseph performs an extraordinary act. He steps into a clear plastic trash bag and, clutching it, falls to the floor and jolts and writhes along within it. You can’t tell whether he trying to shed it the way a caterpillar sheds its carapace or get deeper into it.

Place is one of Cunningham’s greatest works—brilliant, disturbing, conflicted. It’s like a choreographer’s nightmares or the end of a world. The CNDC performers dance it with understanding and distinction. Only one thing disturbed me: the sudden change of lighting just before the main character’s crazed struggle with the bag. The stage was suddenly transformed by what looked like a wash of yellowish light (rather like work lights). I remember the ending happening in a much darker world with only beams illuminating it. That’s in part what made it so startling, so alarming. I confirmed that impression with lighting designer Emmons. Maybe someone misinterpreted the original notes. Interestingly, Cunningham originally wanted, in Emmons’ words, “some sort of device that he could wear and set off that would envelop him in smoke.” Since the possibilities available at the time were toxic, he decided on the bag.

Adrien Mornet and Anna Chirescu in Merce Cunningham’s How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run. Photo: Charlotte Audureau

After such a cataclysmic work, How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run was probably as much a relief to the dancers as it was to us. They wear variously colored tops and dark tights; the women’s hair flies in ponytails. On one side of the stage apron, Gene Caprioglio and Kuhn sit behind a table equipped with mics, a champagne bottle, and glasses, plus the scripts from which they read anecdotes drawn from Cage’s book Silence. Each wry story must told in exactly one minute, so a few are gabbled, and others are pocked with pauses. Occasionally, at the performance I saw, the two readers talked at the same time (an option new to me).

You, the spectator, are charged with listening and/or looking. The talking and the dancing move on parallel tracks. I probably look less intently when a favorite Cage story is being read. (I especially like the one in which Cunningham’s mother is stopped for speeding and can’t find her driver’s license or the car’s registration. She finally tells the cop that she’s sorry, but she can’t spend any more time talking to him. And drives off.)

The agile dancers, with the exception of Joseph, are a little too serious for my taste. But they plunge into the activities with verve. Viallefond takes Cunningham’s part, which means that he makes solo appearances and draws your eye a lot. Holding both each other’s hands high, two women (Pernao and Chirescu, as I recall) skitter in, turning as they go. Later Pernao and Rogeboz enter in a rush, also holding both hands, but wrangling furiously without breaking their grip. Joseph appears to be having a good time hopping.

The title, How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run, gives a sense of the work’s sporty dynamic, without pinning it down. People pass one another and pass on, they kick out their legs, they collapse, and, boy, do they run. They charge in and out of encounters or stay put long enough to dance-spar with obliging friends. They wear themselves out leaping. They clump up in a group effort. But you are not watching a game. Many of the actions, directions, entrances, and exits were determined by chance procedures, so there are no goals beyond the dancers doing what they’re doing at any moment with accuracy and full spirit. And, of course, there are no winners—or rather, every one of them is a winner.

Swinston’s reconstructions for CNDC Angers deserve much praise. Cunningham left us. Long may he live.

Elegant, elegant writing about Cunningham, many thanks Deborah.