Paul Taylor American Modern Dance at Lincoln Center, March 7 through 26.

Paul Taylor’s The Open Door. (L to R): Francisco Graciano, Jamie Rae Walker, George Smallwood, Christina Lynch Markham, and Madelyn Ho. Photo: Paul B. Goode

If Paul Taylor were a visual artist we wouldn’t be so hard on him. Picasso could paint a fish plate and serve lunch on it, and no one would fault it for not being as memorable as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It could even get broken or never make it to the table. A Taylor dance involves a set, costumes, music, performers, and comes burdened with his need to produce at least one or two good new works a year. Since Taylor began choreographing in the 1950s, he has created well over a hundred dances. Some are masterpieces; others are fish plates.

His range is broad. He makes achingly beautiful lyric pieces; dark, weird ones; comedies; satires; and what might pass for revues. He can also startle you by tingeing a sunny dance with shadows or making you question just how comical something actually is. Often, he seems to view his devoted dancers as thoroughbred beauties; at other times, he dredges satanic images out of them. Sometimes he asks the designers who collaborate with him to dress them alike, members of a tribe with strict codes; at other times, he celebrates their individuality by aligning them with characters not necessarily their own. And, as the entity now dubbed Paul Taylor American Modern Dance makes clear in its three–week season at Lincoln Center, his remarkable dancers are up for anything. Tie them in knots, put them in fat suits, reduce them to groveling victims, ask them to play eccentric characters; they can manage any assignment with aplomb, and, after an intermission, be ready to deliver beauty like the very human angels that they are.

Michael Trusnovec and Laura Halzack in Paul Taylor’s Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal). Photo: Paul B. Goode

Imagine the delight of a program that begins with Taylor’s 1980 le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal). How did he ever come up with the idea of combining Vaslav Nijinsky’s 1913 ballet about a ritual sacrifice with a penny-dreadful detective story with a rehearsal for both of the above and set the result to the four-hand piano reduction of Stravinsky’s score (created for Nijinsky to use for his rehearsals and played wonderfully at Lincoln Center by Margaret Kampmeier and Blair McMillan)?

Like a good detective story, Taylor’s Sacre is plotted to convey carefully orchestrated confusion. When the Rehearsal Mistress (Christina Lynch Markham), wearing Cossack attire and held aloft, doles out paper money to three men and three women in neutral practice clothes, they could be both dancers picking up their salaries and thieves being paid off. When the Chinese mistress (Eran Bugge) of the Crook (Robert Kleinendorst) sits at her dressing table, we can see right through her mirror to the Rehearsal Mistress whose every move she is instinctively duplicating.

Designer John Rawling’s portable jail door suffices to define the cell the Detective lands in, caps turn the Crook’s henchmen into policemen, a dagger is obviously cardboard. In reference to Nijinsky’s 1912 L’Après-Midi d’un Faune, as well as to parts of the 1913 Sacre, the dancers much of the time twist their bodies against their feet to created two-dimensional silhouettes and scud across the space, knees bent, looking like cardboard figures pulled along in a slot. Taylor skillfully plays this image of automata against their more impulsive human urges—for example, in a sequence that has three men throwing three bundled-up women onto their shoulders repeatedly or whirling them over and over into off-the-ground cartwheels.

Dancing herself to death. Laura Halzack in Paul Taylor’s Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal). Photo: Paul B. Goode

Everywhere you look, something interesting in the way of choreography shows up. And it doesn’t matter in the least that you’re not always sure of motive. You see that Bugge has kidnapped the baby (an unconvincing brick of red fabric) that the Girl (Laura Halzack) and the Detective (Michael Trusnovec) have been handling fondly, and you can guess that trouble will result. The shenanigans are gorgeous and ingeniously meshed with Stravinsky’s music. The baby gets sacrificed inadvertently when the Crook’s Stooge (Jamie Lee Walker), charged with slaying it, is herself stabbed, and a dying reflex sends her own knife-holding hand up to do the job after all. Halzack is the one who kills herself to the fierce music reserved for the sacrificial dance. A lot of rehearsals end with the dancers collapsed on the floor, and a bit of self-sacrifice marks the life of every one of them.

Of the twenty-one works on view during the company’s season, some are old, some are new, some are masterworks, some are not. Four aren’t by Taylor, among them Larry Keigwin’s Rush Hour and Doug Elkins’s The Weight of Smoke; the Lyon Opera Ballet performs its production of Merce Cunningham’s Summerspace; and Paul Taylor American Modern Dance premieres Continuum by former Taylor dancer Lila York.

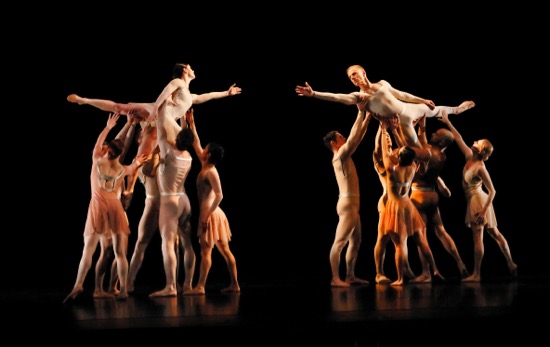

Laura Halzack and Michael Trusnovec and the cast of Lila York’s Continuum. Photo: Paul B. Goode

Since 1992, York has choreographed works for twenty-seven different companies, most of them dedicated to ballet; you can detect that influence on her, as well as the roots she developed during her twelve years performing Taylor’s choreography. Continuum is set to Max Richter’s Recomposed: The Four Seasons, performed by the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, led by Ted Sperling, with Krista Bennion Feeney the violin soloist. Passages from the four famous violin concertos written by Antonio Vivaldi in the early 18th century emerge from and slide back into contemporary pools of sound; at other times, their notes are drawn out, different textures alter them, or other textures well up between them. The juxtaposition of Vivaldi and Richter may have impelled York’s vision of furiously dancing people who glimpse drama out of the corners of their eyes.

It’s evident from the start that York is expert at manipulating groups in space. At the beginning of Continuum, the group of fourteen dancers revolves in a cluster as tightly focused as James F. Ingalls’s lighting. She may weave them into contrapuntal trios—one whirling to the floor as the other rises. Yet her intermittent duets have mysterious dramatic edge. Trusnovec writhes as if suffering in solitude, at first unaware of Halzack, who walks slowly and calmly across the front of the stage. They’re alone together, he jerking and thrown to the floor by unseen forces, she turning slowly on one leg; in the end, he falls, and she thinks about dragging him away. Another duet: To a sweet Vivaldi adagio, Sean Mahoney lifts Heather McGinley in numerous complicated ways, but he does this smoothly, almost dreamily, while constantly revolving and traveling toward stage right.

Michael Trusnovec and Laura Halzack in Lila York’s Continuum. Photo: Paul B. Goode

These people—rushing on and off the stage, forming and re-forming their patterns—wear costumes in neutral colors by Santo Loquasto—all but Bugge, who wears an orange dress. George Smallwood manipulates her (even straddling her as she rolls along the floor), but she doesn’t belong to him. She’s fleet of foot, spins rapidly across the stage, disappears, re-enters and, at one point, faces the others, who seem to drive her away. Parisa Khobdeh collapses while Bugge dances like a whirring insect. Is she the fly in the ointment or the abrasive little element that stirs up a regenerative force? York, like Taylor, doesn’t shy away from mystery. At the end, the backdrop turns golden, and the last we see of the dancers is them turning away from us to gaze toward that expanse.

I was bothered at the beginning of Continuum by the fact that the dancers were doing a great deal of gesturing with both arms, but there is much to admire about York’s work. She enlivens your eyes with the kind of explosive organized complexity that a canon or counterpoint conveys, and she requires full-throttle virtuosity from the dancers, whether they’re leaping or rolling on the floor. They reward her magnificently.

Paul Taylor’s The Open Door. (L to R): Laura Halzack, James Sansom with Christina Lynch Markham, Michael Novak with Heather McGinley, and Michael Apuzzo (hidden) with Sean Mahoney. Photo: Paul B. Goode

Of the two premieres by Taylor, Open Door is only new to New York—that is, it has had time to settle in. It’s one of a number of dances in which he cast the dancers as different character types, —for example, his 2012 House of Joy, or displayed them as performers evoking various dance styles (the 2010 Phantasmagoria). The music he chose this time almost demands a revue format; Edward Elgar’s ghost might be astonished to see selections from his Enigma Variations put to such use. This dance is no portrait gallery of guests at an Edwardian garden party, although the windows and open door of William Ivy Long’s set show strangely painted clouds and foliage. When the curtain rises, Michael Novak (billed as The Host) is rearranging ten red chairs, occasionally tossing off a hint of a dance step in the process. You can tell that it’s important to him that the seating arrangement be a perfect semi-circle.

The guests, glad to be here, are a motley gathering. Some are stereotypes. Mahoney, wearing a red velvet jacket and flourishing a cigarette, swishes around. Smallwood, walking stick in hand, fancies himself upper class. Francisco Graciano is dapper in his uniform, James Samson far sloppier in shorts and any-old sweatshirt, and Michael Apuzzo’s plaid jacket suggests a man who could win big at the track. McGinley’s summer evening gown has a disproportionately fluffy collar, while Christina Lynch Markham wears a plain blue dress that matches the bows on the pigtails of what may be her little daughter (Ho). Jamie Rae Walker is a painter and brings her palette to the party, while Halzack is encased in a fat suit, covered by a brocade gown (red pantalettes under it).

Paul Taylor’s The Open Door. Fighting: Francisco Graciano (L) and James Sansom. Seated (L to R): George Smallwood, Michael Novak, Jamie Rae Walker, and Christina Lynch Markham. Photo: Paul B. Goode

So here they all are. Expectant. The solos and encounters are the refreshments: Ho flutters around, excited and full of beans. Mahoney shows off, but is extremely gracious. Halzack sways sweetly and flutters her hands to a variation in ¾ time (she also has to be helped up after a chair collapses under her). Walker flourishes her palette and daubs the noses of a couple of guests. Graciano starts to clap for her, which leads to a fight between him and Sansom. Novak, attempting to calm the two, intervenes. Whether we see them alone, in pairs, or all on their feet at once, we eventually come to know these people; the performers are expert at defining their characters and how each reacts to the goings-on.

Taylor is the only choreographer I can think of who would end a dance the way he finishes Open Door. Novak is left alone onstage. He rearranges the chairs (a very young child in the audience giggles in delight when he, dragging a chair behind him, drops into a squat to continue his progress). He repeatedly looks toward the door and gestures as if reliving the experience. Novak performs all this with marvelous subtlety. Does he miss them already? No, more likely he’s preparing for—hoping for— the next set of guests. That may be the way Taylor himself feels when the studio door opens on a new day, and a bunch of diverse individuals walks into rehearsal full of hope.

The audience present at Taylor’s world premiere of Ports of Call did not stand and cheer. Devoted Taylor fans may hope he will re-work it or perhaps heave a sigh and bury it. However, it comes elaborately dressed and decorated, which means it cost a lot and hence may be expected to earn its keep. The first three sections are set to Jacques Ibert’s Escales—pretty, bittersweet tunes meant to evoke cities in Italy, Tunisia, and Spain. Taylor has instead dedicated them to Africa, Hawaii, and Alaska. And these are not 3-minute tour-stops like those in The Nutcracker, but sizeable visits.

Loquasto has created three handsome backdrops, at least one of which, for the Hawaiian scene, looks like a giant postcard (palms against almost garish sunset). And the choreography, spatially limited for the most part, suggests that Taylor may have wanted to convey a postcard view of these societies. That is, embrace the clichés, as if we’re tourists, and all this is being staged (or maybe filmed) for us. His artistic viewpoint varies with the climate. Six gorgeously attired men from somewhere in Africa pair up in ritual combat—first at normal speed, then slowed down. Mahoney, their leader, dies, and Michelle Fleet mourns him dramatically and at great length (lovely as she is, you want to yell, “Cut!”). In Hawaii, it’s women in grass skirts with mobile hips and dignified (even pompous) men whose flowered shirts are open to display their manly chests. On the ice in frozen Alaska, three women shiver by a fire, two of them protected by fuzzy white hoods; Trusnovec and Mahoney enter wearing gigantic earmuffs. A pair rubs noses. Two polar bears appear and show what adept dancers they are (Graciano and Apuzzo). Did Taylor intend us to see humor in the earlier vignettes too?

Ibert’s Divertissement accompanies the last section, a church wedding in an impressive setting that looks as three-dimensional as, say, a leftover from 20th-Century Fox’s old back lot. Yes, this part is supposed to be funny. The groom (Kleinendorst) is either so drunk or so scared that, as Mahoney escorts him in, he drops his hat several times in a row. Trusnovec wears his hat down over his eyes, a cowpoke avoiding glare. The bride (Halzack) is pregnant, her mother (McGinley) noncommittal. Kleinendorst makes a second entrance hauling Khobdeh by the rope that’s around her neck (his reluctant horse or. . .?). There’s quite a crowd onstage, and maybe the ceremony got overlooked; the folks sashay in a circle, form two lines for a reel, and the last thing I remember is the bride sauntering out the door alone. The tour is over. May it rest in peace.

In addition to Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal), two other memorable Taylor compositions appeared on the two programs I saw: Company B (1991) and Brandenburgs (1988). These revivals, meticulously coached by rehearsal director Bettie de Jong, show familiar aspects of Taylor’s movement style—its robust buoyancy, along with its earthiness; its lack of pretense; its free-swinging ease. We spectators know that we couldn’t get up out of our seats and join in, yet the dancers look more like us than do those in many other companies. They’re virtuosos for sure, but not averse to showing a few rough edges.

Paul Tayor’s Company B. Eran Bugge teases (L to R): Michael Apuzzo, Michael Trusnovec, Francisco Graciano, George Smallwood, Robert Kleinendorst, and Sean Mahoney. Photo: Paul B. Goode

These two works also show Taylor’s penchant for the unexpected. Company B is performed to songs of the World War II years recorded by the Andrews Sisters, and occasionally, amid the dreams and the high jinks, dancers silhouetted against the sky slowly march along the back of the stage, fall, rise, and crouch to aim imagined guns. When McGinley and Mahoney finish the final duet of the piece (“There Will Never Be Another You”), he seamlessly fits himself into the ongoing parade. It’s a joy to watch Graciano delivering the rhythmic sass of “Tico-Tico,” all the sneakers-and-bobby-socks women throwing themselves at husky Sansom in “Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, Oh!,” Kleinendorst as the rambunctious “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B,” Bugge teasing the men who ogle her in “Rum and Coca-Cola,” and, for contrast, Parisa Khobdeh dancing alone with her memories in “I Can Dream, Can’t I?”.

The flying male ensemble of Paul Taylor’s Brandenburgs: (L to R) George Smallwood, Sean Mahony, Robert Kleinendorst, Michael Apuzzo, and James Sansom. Photo: Paul B. Goode

Brandenburgs is set to two movements of J.S. Bach’s 6th Brandenburg Concerto and Brandenburg #3. The strangeness of the dance’s structure is announced at the outset; six men in sleeveless green velvet unitards banded in gold flank a bare-chested man in paler tights (Trusnovec), around whom three women are posed. There’s no jealousy among these three graces (Fleet, Khobdeh, and Bugge), and Trusnovec dances with all of them. He also watches them while they dance; for instance, he and Khobdeh look on while Bugge performs a wonderful solo wonderfully. Later he dances alone in a corner, spotlit by Jennifer Tipton; it’s as if, balancing on one leg or angling his body in slow, charged ways, he’s pondering a design and how he fits into it. The six men may help him, lifting each woman in turn and passing her to him, but, in their immaculate unison, they’re like an avenue of trees that the others are passing through. Except that they’re voyaging themselves.

I like the fact that Taylor never lists his casts in alphabetical order. Instead, their names appear in the order in which they entered his company; those who’ve been with him the longest come first. He’s a man who knows his dancers for the treasures that they are.

You say “If Paul Taylor were a visual artist …”. Well,, he is that too. Probably not as much as he is a dancer choreographer, but right now I’m looking at a PT signed sketch of a little brown dog wearing a big red bow and sitting in front of a green wreath. There is duality in the dog’s expression. Half of its face seems wild and wolfish whereas the other half is that of a friendly lap dog. If memory serves, PT sent this sketch out as his Christmas card sometime in the 20th Century.

My thanks to George Jackson. Of course, Paul Taylor is also a visual artist. Three small works by him hang on the wall of my apartment (my favorite: a clever black-and-white self portrait with a cut-off toothbrush head for a mustache is framed in a rusty horseshoe), This is a case of a writer getting carried away by her own metaphor. Still, if I put P.T. in bed (so to speak) with Picasso, I have to limit him to the field in which he’s best known. If Picasso was seen to jig in cafes, perhaps I could. . . never mind.