Richard Move and MoveOpolis! performs at New York Live Arts.

Richard Move channeling Martha Graham as Clytemnestra. Photo: JulenPhoto

I have warm, twenty-year-old memories of a cold corner in New York’s meatpacking district (you entered the funky, all red nightclub called Mother on Washington Street and exited on 14th Street). On certain weekends, lines waited to get into the latest iteration of Martha@Mother, the variety show co-produced by Richard Move and Janet Stapleton and hosted by Move looking and speaking remarkably like Martha Graham.

Picture a narrow room with maybe a dozen, ten-person rows of chairs and a bar running the length of the space from the inner door to the tiny red stage. Maybe you have a drink in your hand while you watch one of Charles Atlas’s compilations of film clips of dancing and various characters addressing someone as “Martha.” Then Martha Graham appears onstage. Omigod! Move—elegantly gowned, coiffed, and made up—is six-foot-four. His/her head almost touches what passes for a proscenium arch. And here’s the mind-bending kicker: “Martha,” with her husky, good-little-girl voice, is the evening’s compère, introducing dances by “downtown” choreographers (on one occasion, I was honored to be one of them) that are compact enough to fit on the stage. Dances of which Martha Graham herself would probably never have approved.

Move also choreographed and starred in simulacra of well-known Graham sequences (the avenging Greek choruses, the stiff, scantily clad males. . .). As word got out, he became more daring. In one memorable vignette, “Martha” interviewed Merce Cunningham onstage, gracious and dignified to a fault, but managing to convey that she had given him his artistic start by casting him in her dances (he, as I recall, got off some very clever, good-humored retorts).

After the Martha@Mother period ended, Move took variants of the show to various sites elsewhere. Especially memorable: in 2011, he as “Martha” and Lisa Kron as the New York Herald Tribune’s one-time dance critic, Walter Terry, reproduced word-for-word a public interview that had taken place at the 92nd Street YM-YWHA in 1963.

This year, from March 8 through 11, Martha appeared again in New York in a new iteration titled Martha@20, assisted—as in Martha @. . .the 1963 Interview—by former Martha Graham Dance Company members Catherine Cabeen and Katherine Crockett. The performances opened the Live Ideas Festival at New York Live Arts titled Mx’d Messages. Curated by Justin Vivian Bond, its workshops, performances, films, readings and conversations center on LGBTQI issues, but as Bond noted in a program essay, “Mx’d Messages is a celebration of the world(s) we create when we form alliances with others who live on the margins and when we develop innovative strategies for existing and thriving in the face of extremes and imposing paradigms.”

Planning for the series began during the election cycle, and now that what many of us thought couldn’t happen has happened, the Festival may, with luck, energize those who attend.

One of Atlas’s mind-boggling film compilations is playing in the lobby and in the theater. The Watusi dance from King Solomon’s Mines, hilariously bizarre footage from the late 1990’s tv series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, George De La Pena as Nijinsky going mad in the 1980 Nijinsky, Groucho Marx, Elvis, water ballet, a trained dog, and more, plus the many actors saying “Martha” in varying tones. Oh, and Martha Stewart showing us how to make things.

In Martha@20, Move walks us through bits of Martha Graham’s history in various ways, channeling her and editing her simultaneously. What’s most interesting to me is how he can stir our deeper emotions, and—although he’s profoundly respectful, even reverential, of the woman who periodically takes him over—also make us laugh. That subtle but unmistakable rolling of the eyes, the oracular pronouncements about the art of dance, the way certain words are lightly drawled out, the final consonants bitten off (Martha cherished her “t”s), and the masterfully timed pauses inevitably set us off.

Martha@20: Richard Move as Martha Graham as Mary Queen of Scots in Graham’s Episodes, Part I. Photo: JulenPhoto

She first appears to guide us through Episodes, Part I (1959), her so-called collaboration with George Balanchine to pieces by Anton Webern (in the end, her company performed the first highly dramatic part, along with one principal dancer and three others from NYCB; in his plotless, practice-clothes Part II, Balanchine created a macabre solo for one of her dancers: Paul Taylor). In this resurrection referencing kabuki performances, a goblin stagehand completely covered in black, hands Move/Martha a scepter (perhaps so we’ll know that she is about to play Mary Stuart—the luckless pretender to the English throne), then exchanges that for a tennis racket, removes a golden cloak, and, finally a stand-alone over-gown. Yes, I did say “tennis racket.” One of the most memorable things about Episodes, Part I was Graham’s symbolic staging of Mary’s battle with Queen Elizabeth for the crown; NYCB’s Sallie Wilson and Graham stood on small platforms on opposite sides of the stage and lobbed imaginary balls at each other. Having delivered some well-known Graham anecdotes and remarks, such as “the center of the stage is where I am,” Move-as-Martha swings her racket with grim, but ladylike accuracy.

Film clips of Move’s history as Martha stud her appearances in various glamorous outfits (by Pilar Limosnar). In one scene, she coaches Katherine Crockett through some of the Graham exercises performed sitting on the floor, while Aaron Copland’s music for Appalachian Spring sounds in the background. You can marvel at those contractions in the gut, those exalted releases, those swinging-around legs. In another vignette, Martha rehearses a costumed Cabeen in the vengeful dance of Medea in Cave of the Heart, calling out the movements, urging her to: “Devour! Devour! Spit it out!” as Cabeen lashes her ponytail above the little red snake of fabric that stands for her jealousy. The rope associated with Jocasta’s suicide in Night Journey appears, as does the dagger (cue the heavy chords) with which Clymenestra in the eponymous dance will stab her husband. Move does not copy passages from Graham’s works, but weaves iconic moves and devices into convincing simulations.

Never is the distinction between Move and his avatar more pungent than in the 1930 solo Lamentation. Here is the engulfing purple shroud, but with a male chest glimpsed in its opening. One resonant, if ahistorical touch: this heroine formally wipes her eyes formally while appearing to gaze into the palm of her other hand, as if observing that grief in a mirror. But comedy lurks at the edges of every image in Martha@20. When Crockett returns to deliver a microphone to Martha for the last words of the piece, she leans backward and presents it as a phallus.

Richard Move’s XXYY. (L to R): Catherine Cabeen, Richard Move, and Katherine Crockett. Photo: JulenPhoto

The audience is a knowledgeable one, ready to laugh, to murmur appreciatively, and, of course, to clap. But other responses can be heard during Move’s new XXYY—small, shocked intakes of breath, sighs. Created in collaboration with Cabeen and Crockett and conceived with artist Paolo Canevari and theatrical designer Alba Clemente (the latter also served as dramaturge), XXXY was inspired in part by Autobiography of an Androgyne by Ralph Werther (a pseudonym). This astonishing text, from which Crockett and Cabeen quote during the performance, was published in 1918 by the Medico-Legal Journal and sold only to “physicians, legislators, lawyers, psychologists and sociologists.” In those days, bisexuality was punishable by ten years in prison. Move notes in the program that Werther (also known as Jennie June) “chronicles a transsexual woman’s life in New York City at the turn of the 20th century, a life plagued by violence and discrimination” What’s also tragic is how the author—by nature a “moral” person with insuppressible urges— was forced to view him/herself. The terms that were applied to androgynes and the ways in which they could be attacked bespoke prejudice and anger. How would you feel to live your life categorized as an “invert,” a “eunuch,” a member of a “congenitally defective class,” a ‘sexual cripple?” And to have your behavior considered a “perversion,” an “aberration?” Donalee Katz’s lighting lays bars on the floor.

At the beginning and then again later, Martux_m’s original score gives way to a crackly recording of the singing of Alessandro Moretti (1858-1922), the last castrato employed by the Vatican, made toward the end of his career. The frailty of that soprano is both brave and heart-breaking.

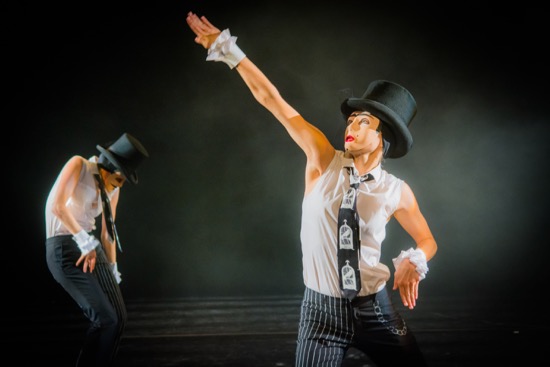

Katherine Crockett (L) and Catherine Cabeen in Richard Move’s XXYY. Photo: JulenPhoto

Clemente’s brilliant costumes query gender distinctions and male-female selves. Cabeen, Crockett, and Move wear no makeup, and, initially, their hair is concealed beneath tight, black Pierrot caps and top hats. They are also masked at first; Crockett’s mask is sad, lipsticked, Cabeen’s sports a mustache; Move’s is paler, its eyes heavier. The costumes tell stories—cuffs but no sleeves, patches of skin showing. Over the course of the work, one or the other of the performers will take off and put on a mask, change striped trousers for a skirt, remove a cap to reveal a flow of hair. The two women take off their shoes and dance barefoot; Move’s high boots stay on.

Their dancing is full of pauses; big moves print themselves on your vision. The two women women also pause, spotlit, to deliver —eloquently—portions of Werther’s reminiscences. Crockett dances alone, wonderfully sinuous in her torso; she and Cabeen move together, erotically linking (did I really see Cabeen bite Crockett’s arm, just before Crockett crawls piggyback onto her? Yes). At least once, they clutch their crotches. Move, when dancing by himself, stoops slightly—hanging his head as if shamed, or perhaps hiding (or querying?) his identity; once, the other two catch him as he’s about to fall (beaten by rough trade?), drag him along, then wrap themselves in a single piece of red fabric and exit together. At the end, Move crawls forward and, finally just stands. Behind him, the sky is blue, and birds sing.

All this is performed with the utmost clarity and a delicacy that doesn’t in the least detract from the fierce sadness of the material.

Thank you so much for this generous review of our work. Just for the record though, in the last picture from XXYY you have confused Crockett and myself. She is curled over on the L with the mustache mask and I am downstage with the extended arm and sad mask. We do switch them later in the show, so the mix up is totally understandable.

Also, it is my solo that immediately proceeds our duet and in our duet, I do bite Crockett’s arm, right before SHE crawls on MY back. The point of the duet is unity and fluidity so again the confusion is understandable.

It is certainly a compliment to be confused with Katherine Crockett, but as we both create our own work when we are not playing twins for Richard I wanted to offer this clarification.

Again thank you for your attention to this work and to all that you have done for dance through your presence and writing.

I am grateful for Catherine Cabeen’s graciously worded corrections and have made the changes to reflect the truth. The photo came to me correctly labeled, but I hadn’t realized that the women sometimes exchanged masks and thought the caption might be incorrect. Wrong. Also, time to confess: my note-taking during performance can mislead me. Here’s what I scribbled: “CC bites KC piggybacked.” You see the trap. Fellow writers beware.

Commenting on your comment on the comment Deborah–I believe Arlene Croce titled her collected dance reviews “Writing in the Dark,” which about says it all. And by the way, I enjoyed reading this highly evocative piece.