Vim Vigor Dance Company presents the New York premiere of Shannon Gillen’s FUTURE PERFECT.

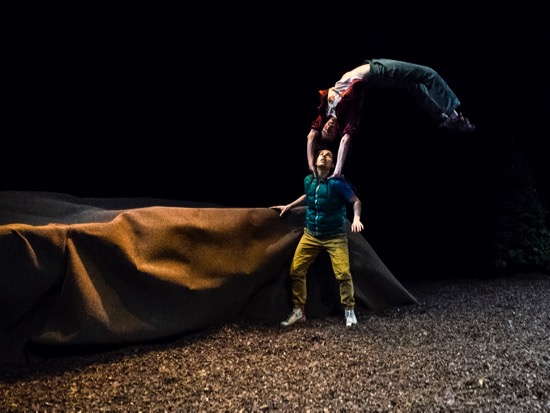

Shannon Gillen’s FUTURE PERFECT. Jason Cianciulli swings Laja Field. At back: Martin Durov and (by the “fire”) Emma Whiteley. Photo: Arnaud Falchier

The woods are full of shadows and lurking danger. We’ve known that ever since we first heard about Hansel and Gretel and Little Red Riding Hood. Too, anyone sitting in the Baruch Performing Arts Center’s black-box theater who saw Shannon Gillen’s Vim Vigor Dance Company perform her Separati last winter knows better than to believe that happy times will be celebrated in the landscape before us. In her new FUTURE PERFECT, the ground looks to be covered in tiny pieces of bark (rubber pellets). Two small evergreens are planted in it, and a pup tent sits near an unlit campfire. Behind these are two large, fake-rock outcroppings (heavy brown fabric skillfully draped over wooden platforms).

These woods are also full of mysteries and delusions. A story is being told, or is it? How much of what happens is imagined by one of the five people who have come together here? What does it mean when someone lip-synchs his or her recorded voice, rather than speaking out? Sometimes, Barbara Samuels’ lighting turns the campsite blue or red or green; is this due to atmospheric change or drug-altered perception (the program defines FUTURE PERFECT as a “psychotropic walkabout”)? Sometimes Martin Durov’s eerie score is full of crackling, grinding sounds, sometimes birds twitter or an owl hoots. Sometimes everything goes black. The title is perhaps a clue, both an ironically idyllic vision and a grammatical tense full of suspense, as in, “soon, he will have come.”

Three of these campers, wearing Joseph S. Blaha’s appropriately rough-and-tumble clothes, are frozen in a tableau when FUTURE PERFECT begins. Emma Whiteley sits by the fire; Jason Cianciulli stands to one side; Durov appears to have just entered, a log in his hands. Laja Field arrives. It is she who introduces the movement palette that dominates the piece. These dancers are also gymnasts and martial artists. They flip themselves and one another; they whirl in the air, dive to the floor, and rebound. They vault onto the rocks and somersault off through the air. They tangle in complicated ways and behave like circus acrobats on acid. What starts as a fight can become erotic, and vice versa. Is their world in flux, tilting them off balance? Are they already hallucinating (as opposed to being drunk, which, at some point, some of them become)?

Martin Durov tosses Laja Field in Shannon Gillen’s FUTURE PERFECT. Photo: Arnaud Falchier

Soon after Field’s arrival, the sound score changes, the lights approximate daylight, and the four of them converse. You gather that Field has set up camp some distance away, and that the others are friendly to her. Maybe she’d like to move her stuff closer. Why are they here, she wants to know? The two men say something about observing meteor showers and then laugh in a knowing way. People intermittently crawl into the tent, two at a time.

Gillen and dramaturge Tom Lipinski must want us to be confused and unsettled, and we are. We sit up straight, keep our ears pricked and our eyes active. I’m tempted to look behind myself, in case something or someone may be coming down the aisle.

Unreality edges in in various ways, some of them astounding, some of them terrifying. Whiteley starts digging under the larger of the rocks and backs away in horror; a human hand is poking out of the dirt. The others help, dig faster, and haul out a woman who appears to be dead. It’s uncanny the way she (Rebecca Diab) somehow slides into and then out of their grasp. She seems to revive, doesn’t, does. Who is this woman they’ve unearthed? She says she was just walking and heard their voices (did I imagine this?). The other two women fix up a sleeping place for her by the fire.

Jason Cianciulli flips off a “rock” with Laja Field’s help. Photo: Arnaud Falchier

Occasionally, these people go crazy; in their private drug-induced fits, they grab handfuls of the pellets and toss them around. Whiteley feels they should notify a park ranger about the “body,” now temporarily missing; the others resist that. Whiteley is given a map that she seems not to be sure how to use and told, “just go!” Instead , however, she brings out a shirt and hat and dresses Cianculli as a ranger.

In one bizarre encounter, three of them appear wearing dazzlingly silver hoods that cover their entire heads. They dance threateningly, then uncover to watch the resurrected Diab and Whiteley fight. In another vision, those two reappear in shabby white dresses, and Field emerges from the tent in a kind of caftan to join them in driving Cianciulli crazy. Diab’s hand gets trapped in his mouth for a few seconds. Field and Diab twist erotically together. Durov has a gun. These are like snapshots, wayward visions of individual, turbulent wildernesses. And the bodies that hurtle through the air and ricochet off surfaces must represent wayward mental states.

It’s no wonder we spectators can’t be sure if we, too, are hallucinating (how many times has Durov entered bearing wood?). Suddenly, briefly, the fir trees light up, and cheesy distorted recorded voices intone a Christmas carol. Field is pushed face down over the occasionally smoking fire, and when she, dazed, recovers and vaults onto one of the rocks, smoke starts pouring out from under her sweater. Omigod! After these self-destructive people have tangled in slow motion, under a flash of blue light, one of them advises Durov that he’s “ready.” In silence, Diab digs into the place where she was first found, and the hollow under the rock suddenly sparkles with tiny beads of light within a golden glow. Durov is advancing toward it when the theater goes black.

Gillen’s amazing dancer-actors combine their daredevil flights through the air with “what’s happening to me?” emotion. You fear for their characters’ lives, that they will forget what they should remember, and that whatever was in the crumpled beer cans by the fire and whatever they were taking in the tent will not wear off before something truly, truly horrifying happens. Or, wait, has it already happened?