The Alvin Ailey America Dance Theater at City Center, November 30-December 31.

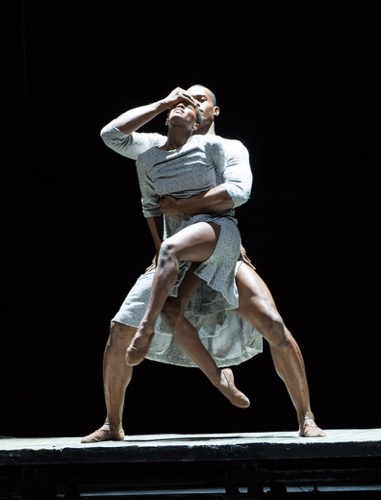

Rachel McLaren and Jamar Roberts of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Company in Johan Inger’s Walking Mad. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Not long after its beginnings in 1958, the Alvin Ailey Dance Company broke an unspoken rule for modern dance companies. Most of those had a single choreographer, who also starred in almost every work; dancers wishing to perform leading roles had to found their own groups. But Ailey created a repertory ensemble, and until his death in 1989, he commissioned new works and remounted classics of modern dance, sometimes making surprising choices. His successor as artistic director Judith Jamison continued that tradition, and Robert Battle, who succeeded her in 2011, has been following suit.

The first premiere of the company’s annual New York season came from abroad. Swedish choreographer Johan Inger created Walking Mad for Netherlands Dance Theater in 2001, while he was still a member of that company, and many other companies have since performed. Inger’s choreography, however, has not been seen much in New York, although I recall with both pleasure and confusion his 2011 Rain Dogs—made for the Basel Ballet but performed in New York by Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet in 2015, just before that company, sadly, was disbanded.

Jacquelin Harris, Glenn Allen Sims, and their shadows in Johan Inger’s Walking Mad. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Walking Mad is full of surprises, and seeming illogic is part of the pattern. It’s also intriguing, and the Ailey dancers, as is their wont, get their teeth into it. Ingber designed the scenery, and that is not surprising; he couldn’t have choreographed the piece without having the set in rehearsals. It consists of a wall that’s almost as wide as the stage and taller than the dancers. Its five doors aren’t immediately apparent; weathered vertical boards cover the whole structure. Dancers pop in and out of its doors, slam against it, and vault up to clamber over it and disappear. In addition, the wall is on wheels, so it can be pushed upstage or folded it into a V; a portion of it can be pushed over and turned into a low platform.

Eventually Maurice Ravel’s famous Bolero is heard faintly, in the distance, and it recurs intermittently before revving up in volume as its repetitive melody explodes into mayhem. Much of Walking Mad happens in silence, but chirping birds and barking dogs accompany Michael Francis McBride’s entry. Wearing a hat and a raincoat, he’s clearly a traveler in a strange land. The first person he meets is Danica Paulos, who is collecting the coats that litter the stage and bearing them away. And just before Walking Mad ends, these two will engage in a strangely poignant duet set to Arvo Pärt’s spare piano piece, Für Alina; in this coda, a coat—held out, handed over, dropped, picked up again—becomes, almost, a ritual object.

Alvin Ailey America Dance Company members Glenn Allen Sims (green), Sean Aaron Carmon (yelow), Chalvar Montero (red), Michael Francis McBride (brown), and Yannick Lebrun (blue) chasing Rachel McLaren. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Crazy revelry figures in the life of this community, as well as visual jokes (a gesturing hand at one end of the wall appears to pluck the jacket off a man standing at the other end). At one point, five of the men (Glen Allen Sims, Yannick Le Brun, Sean Aaron Carmen, Chalvar Montero, and McBride), wearing party hats, chase after Rachel McLaren, who also dons a hat to whoop and holler with them.

There are, however, tender events and violent ones. Harris tangles her limbs with Jamar Roberts, who wears a simple white dress like hers (a brief mirror effect in an open doorway suggest he’s her male alter ego). Jacquelin Harris, alone and disconsolate in the V of the wall, pinned by Erik Berglund’s lighting between her two shadows of herself, is accosted by Glenn Allen Sims and Yannick Lebrun, each of whom dances manipulatively with her, before they bat her back and forth between them. You become familiar with the sound of bodies slamming, or being slammed, against the wall. Harris alternates between allowing the men to brutalize her and attacking one or the other of them. In this passage, as in Mad Walking as a whole, the movement is loose-edged, rough, and forceful. The dancers hunker down, legs spread wide apart; they fling their arms and legs; they hurl themselves into jumps and leaps.

Johan Inger’s Walking Mad. Ailey dancers Yannick Lebrun andr Glenn Allen Sims throw Jacquelin Harris. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

As Ravel’s insistent music pushes toward its climax, the wall is pushed over from behind, and the performers—all but McBride now wearing raincoats and bowler hats—jump onto it and starts slamming out movement. McBride is stamping away in the middle of this rite, but when he falls and rolls, they step over him and keep going. As Bolero reaches its braying conclusion, the dancers, in front of the magically re-erected wall are tearing off their coats and whipping them around. As the last note sounds, they toss them into the air.

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Johan Inger’s Walking Mad. At right: Michael Francis McBride. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Just before this final orgy of dancing, McBride has performed a desperate solo; perhaps he’s beginning to doubt that he belongs here, that he wants to fit in, Now, as Pärt’s music drops its solitary notes into the silence, he and Paulos—slumped, dispirited, and tender with each other—perform their final dance with the coat. Then he rushes at the wall, climbs up to stand atop it, and falls into oblivion.

I have no idea what the terrific dancers think Walking Mad is “about” or even, for sure, what Inger intended. But they dance as if their lives depended on it.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Ailey’s Night Creature. Photo: Paul Kolnick

The performance I attended began with a restaging of Ailey’s 1974 Night Creature by associate artistic director Masazumi Chaya, It’s one of the choreographer’s best—strong in terms of spatial design and its relation to some great Duke Ellington music. As the Ellington quote that serves as a program note says, “Night creatures, unlike stars, do not come OUT at night—they come ON, each thinking that before the night is out he or she will be the star.” The dancers are all hot, and know it. They all have partners, maybe more than one. They’re slinky with their hips, challenging with their gaze, and inclined to hold up their hands like pussycat paws (not that four-legged cats actually do that). Akua Noni Parker and Vernard J. Gilmore are splendid together as the leaders of a crowd of fellow night creatures, such as Collin Heyward, who have their own agendas when not dancing as an ensemble (is Renaldo Maurice startled when Jacquelin Harris picks him up and totes him away? Not really). When her original partner isn’t around, Parker enjoys herself with others (such as Michael Jackson J.) until she’s alone and worn out. But, hey, Gilmore returns to claim her, dance, and (maybe) take her home.

Ailey thought nothing of throwing ballet steps into the mix; dancers hit high arabesques and beat their feet together in the air. Night Creature foregrounds various of the company’s talented individuals. But some of the best images are of the group. Some dancers chase each other through a thicket of arabesques. All of them end the piece leaping across the stage in a series of explosions.

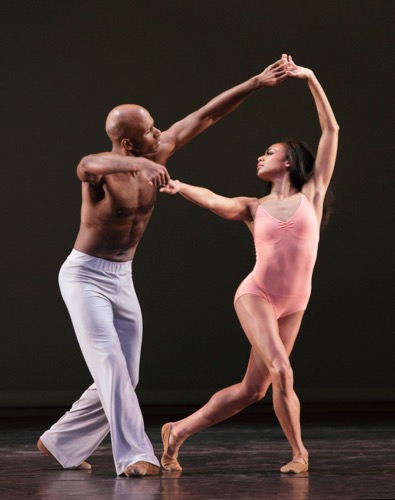

Glenn Allen Sims and Linda Celeste Sims in the pas de deux from Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain. Photo: Paul Kolnick

The program that began with Night Creature included Linda Celeste Sims and Glenn Allen Sims performing the pas de deux from Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain. They have grown into this delicate, exalted duet to Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel, since they first performed it. They’re not just sensitive to each other, they also seem more controlled—not “acting” love’s rebirth so much as feeling it through the movement and not exaggerating its effect on them.

To the audience’s delight, the evening ended with Ailey’s 1960 masterwork, Revelations. And adding to our pleasure, the music was played live by musicians and a chorus and solo singers in the pit. It also seemed to galvanize the dancers. Collin Heyward, Megan Jakel, and Fana Tesfagiorgis performed “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel” with particular fervor. With similar zeal, L. Sims and Jackson attacked the rapturous steps that paved the way for Parker to begin “Wade in the Water” over those rippling streams of blue fabric. Gilmore gave the taut half-rises and inevitable falls of the solo “I Wanna Be Ready” with fine sincerity with mtchint. Roberts, Carmen, and Monteiro lashed themselves dazzlingly through the virtuosic punishment of “Sinner Man.”

Alvin Ailey American Dance Company in Ailey’s Revelatiions. Photo: Manny Herandez

I tend to cringe a little when something in the fine duet “Fix Me, Jesus” gets applause as a stunt. Solo singers Marion Moore and Shelton Becton made the beautiful prayer sound deeply heartfelt, and with matching sincerity, Sarah Daley and Jeroboam Bozeman approached the dialogue between a sinner and a man (perhaps a minister) who supports her. I was glad that audience was silent, hanging on every move, and only twice applauding—once when she held one leg steady in the air and slowly revolved without his help, and more vociferously when she leaned slowly back against his supporting arm. (If only Daley could refrain from arching so far back! It takes her eyes off heaven feat and makes her seem to be presenting the move as a feat.)

But clapping along during the final, ebullient “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham” feels just right. We’re part of the congregation for those women in their yellow dresses with their hats and fans and those Sunday-best men. Barbara Forbes’ redesigned costumes give every lady churchgoer a rhinestone brooch (an unfortunate bit of eye-catching glitz), but the performance never loses its down-to-earth joy.

Vivid and evocative writing as usual! . Liked the “thicket of arabesques” image. I agree with you about the back bend in Fix Me Jesus — even a hint of showing off ruins the mood although heartfelt applause may be natural and spontaneous. I remember two Royal Ballet dancers being interviewed on the BBC in London after a New York trip and saying that they felt encouraged by it — and preferred it to Covent Garden audiences who waited until the end. I, on the other hand, LOVED the English audiences quiet absorption — they really seemed to be paying attention — and never more so than when you’d get a prolonged silence at the end of something tragic like a really great performance of Giselle. Also agree about the sparkling brooches — that section is so lively, so full of life — no extra sparkle needed.