Lucinda Childs Dance Company samples fifty-three years of her choreography at the Joyce, November 29-December 11.

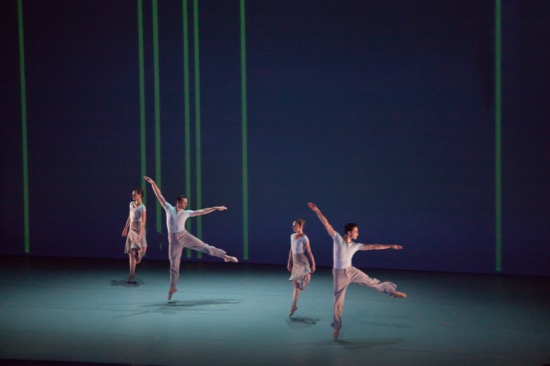

The Lucinda Childs Dance Company’s Sarah Hillmon, Anne Lewis, Katherine Helen Fisher, and Shakirah Stewart in Lollapalooza. Photo by John Sisley.

When I first saw Lucinda Childs’ choreography in the early 1970s, I knew little about Judson Dance Theater, which had presented her as a radical worthy of being linked with Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, et al. Nor was I a seasoned critic. What fascinated me then was her juxtaposition of simple, active, everyday movements (e.g.walk, run, jump, somersault, sit, lie) with immaculately designed structures.

Repetition had become an important element in her dances by then. Watching the patterns she had created, I would try to figure out their mathematics and how changes developed over time. That, I felt, was a necessary part of spectatorship when it came to Childs’ work, as it was with that of other choreographers investigating extreme amounts of repetition (notably Laura Dean and Molissa Fenley). Climax played no role that I could detect, but a certain ritualistic drama crept into her pristine pieces because the dancers weren’t automatons, but athletes who drove themselves hard, breathed and sweated and won our admiration. Especially as her dances became more complex, more arduous.

In the 1980s, Childs began to work extensively in Europe, choreographing for other companies and creating dances for operas, having created her masterwork Dance in 1979. (Dance, set to a score by Philip Glass, will be shown during the second week of her company’s season at the Joyce.) The first week is devoted to a program titled “Lucinda Childs: A Portrait (1963-2016). It begins with Childs’ solo Pastime and ends with the New York premiere of Into View.

Watching various of her twelve dancers perform eight works over an hour and 45 minutes (with a 15-minute intermission), I find myself not only trying to fathom the structures, but to notice what distinguishes one from the other. All are sensitively lit by John Torres, and the dancers in each piece wear plain, elegant clothing by Carlos Soto—differing only when the women wear skirts instead of trousers.

Lucinda Childs Dance Company’s Katherine Helen Fisher in Pastime. Photo: John Sisley

Pastime (1963) was originally a three-part solo, performed by Childs herself. Fifty-three years later, she has parceled it out to three dancers, and Torres’s spotlights emphasizes the fact that the solos “travel” across the stage, even though all are stationary. Each is built around an unusual difficult task. And all are accompanied by intermittent bursts of a score by Philip Corner that sounds like an avalanche of falling objects mixed with fast-running water.

Caitlin Scranton, in profile, balances on one leg for a surprising amount of time, extending the other like a pointed probe, swinging it from the knee down, flexing her ankle, twisting slightly to survey us. Katherine Helen Fisher reclines on her back, her shoulders and feet pressing against a gray sheath (picture a fabric bathtub). Most of the time she keeps her eyes on us, as she stretches one bare leg or bends her knee so that her beautifully pointed foot may aim for the floor outside her domain. She begins and ends in profile, but also maneuvers to face us. And most of the time, both her upper body and her legs are slightly off the floor (think stomach muscles). In the last and briefest episode, Anne Lewis, her back to us, has bent so far forward so that she looks at us through a cage of the legs and curved arms that brace her. Her final task is to stand on one leg, still doubled over, and spread her arms like wings.

Only the muted sounds of the dancers’ feet accompany the next three pieces: Katema (1978) for four women, Radial Courses (1976) for four men, and Interior Drama (1977) for five women. The first stars diagonal paths. Shakirah Stewart in a near corner and Sharon Milanese opposite her in a far one establish a pattern of walking to meet in the center of the stage, swing an arm to propel a half turn, and retreat. After this has been going on a while, with subtle changes, Katie Dorn and Sarah Hillmon stake out a path between the remaining two corners, but since the timing and the distance that the walks cover differ from the original paths, the two units do not cross each other without spectators realizing how easily they could collide.

The Lucinda Childs Dance Company’s Lonnie Poupard Jr., Matt Pardo, Vincent McCloskey, and Patrick John O’Neill in Radial Courses. Photo by John Sisley.

There’s no such hint of drama in the brilliantly designed Radial Courses. The four men are paired by size, as the women were in Katema: Lonnie Poupard, Jr. and Patrick John O’Neill (the taller two), Vincent McCloskey and Matt Pardo (the shorter ones). Their pattern is a big circle, whether they travel it clockwise or counter clockwise, and they tend to stay close together. I can’t think of the proper term for their walk; a combination of “scuttle” and “skim” might do it. They take tiny, smooth, rapid steps, maintaining their bodies as single erect units; their arms stay at their sides; they look neither to left nor right. Dressed identically in tight-fitting white leotards and white pants, they might be a cadre of wind-up toys, slightly less “human” than the dancers I recall from a 1994 revival. The pleasure of watching them comes from the ways in which their breakout phrase occurs: a little hop, kicking one leg out in front of them, followed by a low leap and more walking; individually, in pairs, or collectively, they flash that pattern in many ways.

The main issue in Interior Drama involves one unit of three tall women (Katie Dorn, Lewis, and Scranton) and two shorter ones (Milanese and Stewart). All are identically clad in white leotards and pants. The title does not refer to individual struggle, but to the way the patterns function. Facing the audience, the women establish a few moves, one of which involves bouncing lightly as they swing their legs from side to side. As the groups travel forward and back, they interweave—the two smaller women, say, backing up on individual curving paths to re-situate themselves in relation to the other three. And, at times, the whole design seems to move right or left—a surprise when you suddenly notice it.

The post-intermission dances—Concerto (1993), Lollapalooza (2010), Canto Ostinato (2015) and the 2016 Into View—reveal developments in Childs’ style. This may be due to her experiences in opera and/or to the mellowing that can attend age and experience. All four pieces are performed to recorded music at the Joyce performances: Henryk Gorecki’s “Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings” for Concerto, John Adams’s “Son of Chamber Symphony” (third movement) for Lollapalooza, Simeon ten Holt’s “Canto Ostinato” for Child’s eponymous dance, and “The Sun Roars into View” by Colin Stetson and Sarah Neufield for Into View.

And although almost all these four selections involve repeating units, they are all rich in texture. In them, lighting plays an important role, changing not only the way it hits the dancers but for the hues that the cyclorama turns. The dancers are still costumed identically by gender, but some of the outfits involve color.

The Lucinda Childs Dance Company’s Katie Dorn, Patrick John O’Neill, Sharon Milanese, Caitlin Scranton, and Anne Lewis in Concerto. Photo by John Sisley.

After 1994, Childs didn’t present a company in New York until 2000, but in Concerto, some of the elements that had defined her style were developing further. In it, seven performers come and go (in the cast I saw: Sarah Hilmon, Lewis, Milanese, Benny Oik, Poupard, Scranton, and Stewart). Their steps are light, springy, skimming. You could consider them in ballet terms: sauté, jeté, assemblé, cisonne, rond de jambe, passé, pirouette, arabesque, renversé. But that would be a mistake. Think instead of what those terms describe and then imagine the actions performed smoothly and without fanfare or extremes of height: hopping on one foot, jumping on two, leaping from one foot to the other, springing from one foot to two or from two to one, turning in various ways, and positioning the legs expansively (lifted straight behind the dancer, flicked up bent to form a diamond against the other leg.

The Lucinda Childs Dance Company’s Shakirah Stewart, Lonnie Poupard Jr., Vincent McCloskey, Sarah Hillmon, Benny Olk, and Katie Dorn in Lollapalooza. Photo by John Sisley.

In Concerto, to Gorecki’s remarkable music, when Childs introduces clear two-part or three-part counterpoint, it doesn’t require mathematical sleuthing on the part of the public. Seventeen years later in Lollapalooza, the circus sounds in Adams’ music inspire not just the perky, tilted side leaps with which the dancers frequently enter, but occasional smiles. Also a flirty palms-up sway that makes you think of old-time movie jazz. In this lively work, the four men are attired in orange and red, and the four women wear shades of yellow (one of them in pants). Here, for the first time all evening, men lift women—often a quick pick-up, whirl, and set-down that doesn’t aim for a beguiling pose. When the pairs are in a diagonal line, a lift travels down it, pair by pair. For the first time, dancers hold hands to form arches. And the lighting may put them in a sunny place or silhouette them against a blue backdrop.

Only two pairs appear in Canto Ostinato to ten Holt’s minimalist score, and the stage refers to their intersections through Torres’s lighting: one, then two, and eventually eight slender, pale green columns of light sidle from side to side across the cyclorama, bumping into one another, augmenting and diminishing. That’s not what the gray-clad dancers do. The focus is on duets: Scranton with O’Neill, Milanese with Pardo; sometimes one brief duet echoes another, sometimes they function contrapuntally. Any manipulations or assists by the men of their partners have the look of trying things out, more collaborating than domineering or showing off.

The Lucinda Childs Dance Company’s Caitlin Scranton, Patrick John O’Neill, Sharon Milanese, and Matt Pardo in “Canto Ostinato.” Photo by John Sisley.

“The Sun Roars into View,” the music for Into View, is the wildest of the evening. Composer Colin Stetson is a saxophone master and his co-composer, Sarah Neufeld, is a violinist, but what the two of them get up to together is exciting, and muted voices and other electronic effects are part of the texture of the piece. The dancers are not on a secure rhythmic loop; they slide above the sounds, dip into them, meet them in a clinch. Eleven participate in this most recent Childs work, entering and leaving, dividing and subdividing. Torres creates a tiny sun of light on the backdrop. You may see—for an instant anyway—five pairs in unison. But one image recurs amid the light-footed voyages of individuals: a man and woman meet centerstage, raise their arms and press their palms together to initiate a pact, after which the man briefly partners the woman, before they separate and join the busy traffic; before long, another pair has picked up their theme. It’s as if that interaction is a road block to be negotiated or a rest stop to be taken.

If this program is a portrait of Lucinda Childs, how does it paint her? She’s as precise as a mathematician, as fastidious about spatial design as an architect. Her charts and scores are on display this Fall in a gallery north of Paris, in an exhibit revealingly titled “Nothing Personal.” Her works are handsome (as is she) and rhythmically driving (insistent even). However, they are also cool in tone, even, at times, icy. They have a certain hauteur. If you met one on the street, you might not feel like embracing it; perhaps you’d bow or proffer a handshake. But they are also optimistic in their lightness and springiness; dark tones don’t haunt them. Occasionally, Childs surprises you with, say, a shift of dynamics. Occasionally, she reveals a trace of dry wit.

Her dances often rewind back to their initial images. We view momentum or development, I think, through the dancers. They are not inert like paints waiting on a palette. Without showing fatigue or stress, they perform what I know to be heroic feats of endurance, rhythmic acuity, and memory. You can barely detect hard breathing.

This amount of lean, immaculately engineered, repetitive patterning, however enthralling to some, is not everyone’s cup of tea. After the applause for the first half of the program had diminished, the woman behind me asked her companion what the title of this last dance was; he replied, “it’s called ‘too long.’” I’m sure he revised his opinion after seeing the less austere second half of the evening. However, “Lucinda Childs: A Portrait (1963-2016)” did at times seem long, compelling though most of it was. At the end, the audience gave the dancers a rousing ovation. Then those onstage smiled and shifted their weight and became more like most of us—we who could never do what these twelve had achieved and do it with the devotion that they bring to Childs’ formidably beautiful designs.

Thank you for this caring and all-seeing embrace of this performance.

I couldn’t possibly agree more with Jonathan Stein. Thank you so much for your highly knowledgeable perspective and the elegance of your expression of same.