Danspace Project’s Platform 16: Lost & Found revisits and examines the decades when HIV/AIDS felled so many.

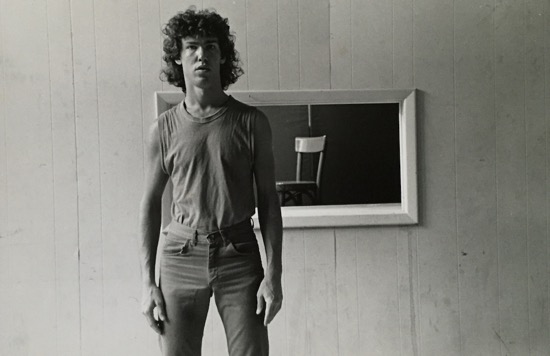

John Bernd in the 1980s, photographed by Dona Ann McAdams in front of an image of his red chair.

I look around St. Mark’s Church. It’s really filling up; people are sitting on risers well beyond the usual cut-off place. Friday, November 4th is the second night of this three-night performance: Variations on Themes from Lost and Found: Scenes from a Life and Other Works by John Bernd. The event is just one in Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost & Found, which began on October 13 and will end on November 19. Tonight’s program contains this note: “This Platform is dedicated to all those who died, and to all those living with HIV who teach us to live with grace, creativity, and courage. We mourn for those lost in hopes that their shimmering traces will be found by current and future generations.”

I look around again. There are survivors here—meaning not just those who survived the AIDS epidemic physically, but those who survived losing their friends, colleagues, and loved ones. Yet seated in the audience are also people who were infants around 1981, when the mysterious symptoms began to appear and people started dying. (By 1994, AIDS was said to be the leading cause of death among Americans ages 25 to 44. The death rate slowed down around 1997, because the FDA had approved the first protease inhibitor two years earlier.) Those who were infants or children during those decades need/want to know what they were like.

How many are familiar with John Bernd’s name—saw him dance, saw his choreography, heard the music he made, saw his drawings? He appeared on the downtown New York scene in the late 1970s and died at age 35 in 1988. I regret that I didn’t know his work better. I’ve learned much about him and others from looking at the superb catalogue of the Platform: Lost and Found: Dance, NYC, HIV/AIDS, Then and Now (editor-in-chief: Judy Hussie-Taylor; editors: Ishmael Houston-Jones, Will Rawls, and Jaime Shearn Coan); it’s available at Danspace. A valuable slimmer publication, AIDS OS Y Version 10.11.16 offers poems, memories, and artwork evoking those years of rage, confusion, and grief.

One page of the catalogue reproduces the calendar of a particular October week late in Bernd’s life, with visits and duties marked out for those who were helping him: Annie Iobst will take him to the doctor at 4 on Friday, Dona Ann McAdams will spell John W. on Saturday, Jane Comfort will visit on Sunday. Fourteen people’s phone numbers are listed in case of need. It evokes so powerfully that time in the city when none of us wanted a person we loved not to have a friend who could take laundry to a laundromat and come by and try to be encouraging. Lori Seid, stage manager of P.S. 122 back then, wrote memorably elsewhere in the catalogue about her daily visits to Bernd during his last week of life.

I saw Bernd dance at P.S. 122 in March, 1988; he died in late August. It was a duet by him and Jennifer Monson called Two on the Loose—partly improvised, I guess, since he’d been in the hospital during what was supposed to be their rehearsal period. He spoke calmly about his days as an inpatient (the lack of privacy, the violence of treatment, the food). He was no longer the sturdy, curly-haired dancer in the picture above. You could tell he was determined to survive, but the contrast between the two performers was unavoidable. In writing about the piece, I compared “Monson’s strength, rosy-cheeked health, knockabout dancing and Bernd’s paleness, seriousness, fragility.” I never mentioned AIDS, since— as I recall—he hadn’t, but I did remark that “these days” the definition of virtuosity had expanded to include a new feat called “surviving.”

Variations on Themes from Lost and Found (dress rehearsal). Charles Gowin standing in basin, Johnnie Cruise Mercer leaping. Alex Rodabaugh and Talya Epstein (in blue), and Alvaro Gonzalez washing Madison Krekel. Photo: Ian Douglas

In the section of the catalogue that’s devoted to Bernd, Jennifer Monson remembered a moment in Two on the Loose, when she dipped a washcloth into a white basin of water and washed his bony back, “our bodies humming in Carol McDowell’s lighting.” That moment is re-created at St. Marks, this time in Carol Mullins’s lighting. Madison Krekel sits in the little red chair, and Alvaro Gonzalez washes her back. Charles Gowin stands in another basin in another spotlight, slowly sponging water over himself. Meanwhile Johnnie Cruise Mercer is repeating many times a strenuous phrase of dancing. He advances along a diagonal, retreats to his starting point, begins again. Again. Again. He gives it his all every time, but you can see his fatigue growing, along with his determination not to give up.

The above details may hint at how the work was structured and co-directed by Houston-Jones (who performed in all the versions of Bernd’s Lost and Found: Scenes from a Life in the 1980s) and Miguel Gutierrez. There are no photographs of Bernd projected (you can buy the book) or of his friends. Houston-Jones and Gutierrez did not wish to present an anniversary memorial of some kind; the event is instead about remembering and evoking an artist’s many visions of his work during a time of crisis. They call the result a “re-imagining.” It’s a beautifully structured collage—devoid of sentimentality, witty, potent, and deeply moving as well as invigorating. We see phrases from dances choreographed by Bernd that have been set into unison passages and contrapuntal patterns. We hear his music recorded or sung. We hear his words recited. We see a series of projected spare black line drawings on white paper; they show a horizon, a highway passing through emptiness, and an occasional “temple” (his term)—two outlined supports with a beam laid across the top, some near the spectator, some tiny and distant.

The cast at the beginning of Variations on Themes from Lost and Found: Scenes from a Life and other works by John Bernd. (L to R): Talya Epstein, Alvaro Gonzalez, Johnnie Cruise Mercer, Alex Rodabaugh, Tony Carlson, Madison Krekel, and Charles Gowin. Photo: Ian Douglas

We are given a chance to get to inspect and identify the eloquent performers, as they walk in, wearing basic white underwear; entering one by one, they line up in front of us, and look at us for a while: Tony Carlson, Talya Epstein, Gonzalez, Gowin, Krekel , Mercer, and Rodabaugh. The work is not separated into single “numbers.” The images overlap, combine, and dissolve from one episode into another, or gradually accumulate into a pose or a passage of dancing. Nick Hallett has skillfully arranged and re-mixed some of Bernd’s musical compositions, adding recordings by others, including Prince and Lou Reed. In one bout of dancing, during which the performers gallop about, barely missing one another, it took hearing music from Aaron Copland’s score for Rodeo to make me see their pumping arm gestures as pulling on reins. And smile about that.

Tony Carlson holds Charles Gowin in Variations on Themes from Lost and Found; Scenes from a Life and other works by John Bernd. Photo: Ian Douglas

Bernd performed quite often in others’ works (including some by Meredith Monk, whom he considered a mentor) and in the Open Movement sessions at P.S. 122. Somewhere along the line, he’d studied modern dance. The movement shown in Variations on Themes. . . is full-out dancing with a loose swing to it and all manner of jumps and leaps. The performers also stomp and clap rhythms, having donned shoes to do it (this passage from Bernd’s Lost and Found (Scenes from a life), part II). It’s spirit-lifting to watch them in three-part counterpoint (maybe not Bernd’s choreographic patterning, but one whose design he’d surely have liked). They run at partners and are lifted and made to rebound back and try again. But there are also moments in which they fall or wilt or roll on the floor. Rodabaugh, suddenly naked, lies prone and motionless for a long time; later, he crawls on his belly for a long journey from one near spot to a far corner. Here and there, you see images of one person helping another, touching him or her gently, or struggling with someone. One repeated position: squared-off arms held as if someone has called, “Hands up!”

When the cast members pose, they do so casually—some standing, some sitting on the floor, as if waiting for something. Once, anchored like this, they sing syllables that sound like variations on “O-hi-hi-hi, hi-ya.” (I’m not being accurate about this, but maybe you get the picture). It makes me think of Bernd’s days with Monk. The performers build the rhythmic chant into harmonies.

Medicating as ritual. Around the blender (L to R): Alex Rodabaugh, Charles Gowin, Talya Epstein, Johnnie Cruise Mercer, Alvaro Gonzalez, Tony Carlson, and Madison Krekel. Photo: Ian Douglas

In one scene, wit and terrible pity mix. A table carrying a blender and a variety of pill bottles and stuff like parsley is wheeled into the light, and the cast members take turns tossing items of medication and food into the pitcher, while Carlson identifies each, as if he were a chef preparing some delicacy (yes, this was an event that happened daily in Bernd’s life). We laugh because they’re filling the blender impossibly full. When the lid is on, they all put their hands on it and start the motor, yelling as fiercely as if this were a tribal ritual. In the end, they tidy up, and Carlson takes a swig of the potent greenish glop as he walks away.

You can read about Bernd’s endurance, his will to live, and the grim, painful accounts by his friends in the “John Bernd Zine” within the Platform catalogue, along with words about and by many others who experienced those life-consuming decades on the Lower East Side and elsewhere. Juxtaposing that reading to glimpsing the art that Bernd created during the last seven years of his life is a stirring experience.

Remember that there are other events to come at St. Marks during the Platform: performances, conversations, talks, a vigil. Let memory serve our future.

Thank you for your thoughtful report of “Variations on Themes from Lost and Found: Scenes from a Life and Other Works by John Bernd.” I (as I always have) value your views, There was a lot to take in and I want to make a few clarifications for history’s sake.

In the reprint of the zine that appears in the catalogue Jennifer Monson misremembers her and John’s positions in the last image in “Two on the Loose.” In the video of the performance, John is washing her back, (although it may have happened the way she recalled in a rehearsal.)

Miguel (Gutierrez) copied Johns’s solo stomping pattern in boots directly from the video of “L & F pt 2” and taught it to the dancers, so it is in fact John Bernd’s choreography there.

The blender scene is from “Surviving Love and Death,” and each of the performers puts a different ingredient into the blender before they do the chant: This scene was lifted directly from the video.

As I said, there was a LOT to take in, John Bernd’s work was so varied and far-reaching that errors of memory are inevitable. (eg: Jennifer mis-remembering the back washing set-up.) Your thoughts and observations and capturing the spirit of the piece far out-weigh any minor discrepancies.