Mark Morris curates “Sounds of India” for Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival.

Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris’s Pure Dance Items. Fully visible (L to R): Rita Donahue, Noah Vinson, Nicole Sabella, Billy Smith, Domingo Estrada, Jr. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Mark Morris has made many trips to India, beginning in 1981. I’ve only gone in my dreams. My fascination with the country’s dance styles came from seeing New York performances by visiting companies, dipping into epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, treating my dance history students to videos and master classes, and taking some Bharata Natyam classes.

Morris curated the ten-day “Sounds of India” programs featured in Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival: four music programs, the Nrityagram Dance Ensemble performing in the Odissi style, and the Kerala Kalamandalam Kathakali troupe presenting The Killing of Dussasana (a wonderfully gory and heroic version of an episode in the Mahabharata. I missed seeing Nritygram this time and faced a schedule conflict when immigration problems caused the first night of the Kerala Kalamandalam to be canceled and re-scheduled.

I mention what I didn’t see because of the influence of Indian dance on the Mark Morris works that the choreographer chose to program during the “Sounds of India.” He doesn’t, in these, copy steps in the vocabulary of Indian dance, although he may allude to aspects of the styles, the forms, the rhythms, the patterning.

Stacy Martorana and Brian Lawson performing Mark Morris’s The “Tamil Film Songs in Stereo” Pas de Deux. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Two of the dances date from the 1980s, The “Tamil Film Songs in Stereo” Pas de Deux (1983) and O Rangasayee (1984). The first is a delicious comedy. The part of the title in quotes refers to a mysterious cassette tape (perhaps the audio of a scene from a movie?) that Morris picked up in India long ago. What you hear is an increasingly irritated Indian man coaching an increasingly tearful female student in a song. Morris turned it into a dance lesson. Brian Lawson gives a hilarious performance as the teacher, first seen reading a magazine while birds twitter. The student (Stacy Martorana, equally comical) is late. Adamant and impatient, he demonstrates a few big, emphatic, clearly defined steps (the singing teacher provides a warm-up scale). She follows as best she can.

The choreography itself is wonderfully screwy: now he wants her to creep along, to wiggle the hips, to explode in flowery leaps (feet flexed). She practices while he exits the stage (a bathroom break perhaps). He wears her out; the singer weeps as she chants the syllables, the dancer stumbles and grimaces. Still, she gets to wear the net skirt hanging on the barre and an absurd headdress. So I guess she’s ready for her debut.

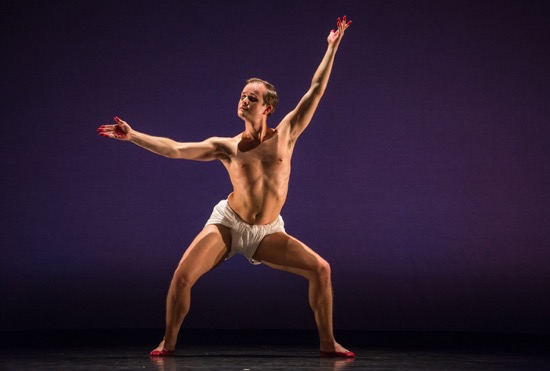

Dallas McMurray performing Mark Morris’s O Rangasayee. Photo: Stephanie Berger

O Rangasayee is a deeper experience. The music is a Carnatic song of that name by Sri Tyagaraja and performed (again on tape) by, I believe, the great M.S. Subbalakshmi and others. Morris made this twenty-plus-minute solo for himself and has revived it for Mark Morris Dance Group’s Dallas McMurray. Lois Greenfield’s iconic photos of Morris dancing O Rangasayee in 1984, dark curls flying, remind me how precise the moves have always been. Any differences between his performance and McMurray’s may be in part the difference between memory and actuality. Watching McMurray, I’m more aware of the dance not just as devotional, but as an ordeal he gladly entered upon and by which he is eventually transfigured.

McMurray, clad only in a short, draped, white garment draped around his hips, his hands and feet outlined in red, begins at the back of the stage, crouched in dim light, hearing, as we do, the light percussion of the tabla and quietly singing voices. It takes him a while to rise and straighten up. As in Indian styles, whether Bharata Natyam from the south of India or Kathak from the north, he gradually builds a phrase of movement, adds to it, creates variations of it—in this solo, that means arresting its flow in held balances, condensing it, performing it in slow motion, expanding it in space. Certain steps evoke those Indian styles too, but altered and out of context. Here are some of them: McMurray sinks into wide, bent-kneed positions; lets his head wobble slightly; presses his fingers together and arches his wrists; grasps one index finger in the other hand and wreathes his arms overhead; flexes his ankles; takes tiny steps on his heels; circles the stage, spinning as he does so. Philip Sandstrom’s lighting design subtly alters the space for him.

What begins as a dutiful personal ritual becomes ecstatic, without any loss of control or clarity. The dancer enters the dance, or perhaps it’s the other way around; through the fatigue that we see—feel—he reaches a kind of transcendence. A superb achievement for McMurray.

Lesley Garrison, with finger cymbals, performing Mark Morris’s Serenade. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Composer Lou Harrison was influenced by the music of Asia—the gamelans of Bali and Java rather than the sounds of India. The MMDG program began with a solo, Serenade (2003), set to his Serenade for Guitar (played onstage by guitarist Robert Belinić and percussionist Stefan Schatz). To the music’s five sections (“Round,” “Air,” “Infinite Canon,” “Usul,” and “Sonata”), Lesley Garrison, costumed handsomely by Isaac Mizrahi and lit by Michael Chybowski, dances with several different props that influence her moves. She begins seated and, to a simple melody, with very light drum accents, makes patterns with her arms and shoulders (some wing-like in a subtly Balinese way), and bends her torso. In the second section, she moves slowly, concentrating on the gleaming pole that she’s manipulating. Next, it’s a fan that she wields, and her moves are often staccato, like Schatz’s single aggressive rim shots, seasoned by tiny, mounted cymbals. Garrison plays finger symbols herself for “Usul” (the word refers to a rhythmic pattern used in Ottoman classical music). She’s looser for the final section—flying about, falling back, grabbing the leg she has just kicked up. Castanets join in (some of their flurries produced by backstage hands). Garrison rises charmingly to the challenges.

Rita Donahue pulling Durell R. Comedy and (hidden) Brian Lawson in Mark Morris’s Pure Dance Items. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Morris’s world premiere, Pure Dance Items, is set to music by Terry Riley, who, although his experimental roots developed in San Francisco, studied with a master of classical Indian vocal music and, with him, traveled frequently to India and played there. Six excerpts from Riley’s Salome Dances for Peace are performed by the string players of the MMDG Music Ensemble (Georgy Valtchev, Anna Luce, Jessica Troy, and Michael Haas).

Elizabethan Kurtzman has dressed the twelve dancers in sporty, outrageously vivid outfits, and at the outset they just stand facing us, glancing from side to side in unison and making designs with their arms. Take a good look; they’re a handsome bunch: Sam Black, Durell R. Comedy, Rita Donahue, Domingo Estrada, Jr., Lawson, Aaron Loux, Laurel Lynch, Martorana, Brandon Rudolph, Nicole Sabella, Billy Smith, and Noah Vinson.

With subtitles like “Fanfare in the Minimal Kingdom,” Riley’s music implies a story. The dance’s title, however, may be a reminder that in India, there’s a distinction between a “pure dance” form and one that tells a story through gesture and facial expressions. In Pure Dance Items, the sequences of dance and music are clearly demarcated, and dance and music mate clearly within them. Sometimes the dancers back up and start over; sometimes they exit. They’re not all onstage the whole time. They may point up the contrast between opening a hand into a flat palm and closing it into a fist. They may form a kind of frieze or move in a line from the front of the stage to the back. They may seem whirled by the music. Patterns pass through patterns. (I need to see it again; it’s a richer and more complex work than I’m making it sound).

Mark Morris’s Pure Dance Items. Stacy Martorana and Domingo Estrada, Jr., with Brandon Randolph leaping. Photo: Stephanie Berger

One intriguing and enigmatic device appears, disappears, and reappears throughout Pure Dance Items. During the opening passage, Black is seated on a stool, facing the audience, doing what the others do, but without rising. Intermittently, others will use that stool. Sometimes a second person stands slightly in back of the first, placing a hand on his/her shoulder; sometimes a third joins the tableau. What are they staring at? Once Smith, stands on the stool, one leg lifted in front of him, and balances there, rock-solid. (I think he looks like a cowboy.) Are the seated watchers seeing the dance behind them as if in a mirror, before they rise to join it again? Could be. Or not. Anyway, a fine new, astutely musical dance by Morris. I’ll bet it’d play well in India too.