Vail Dance Festival: Re-Mix NYC performs at City Center, November 3 through 6.

Vail Re-Mix performers in 1-2-3-4-5-6 (L to R): Lil Buck, Michelle Dorrance, Robert Fairchild, and Melissa Toogood. Photo: Erin Baiano

Damien Woetzel is celebrating his tenth year as director of Colorado’s Vail Dance Festival. And whatever you might have expected from a former principal dancer in the New York City Ballet, Vail Dance Festival” ReMix NYC is probably not it. Still, you may have had glimpses of others of Woetzel’s projects before the current City Center season. One project is to resurrect certain “lost” dances; the other is to bring together performers from different companies and disciplines. It was Woetzel who paired ballerina Wendy Whelan and postmodern dancer-choreographer Brian Brooks at Vail in 2012, with stunning results (you can see the duet in progress at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wBQTTBZ7hWE). It was Woetzel who brought jookin’ prince Lil Buck together with master cellist Yo-Yo Ma in 2011 to perform a version of The Dying Swan that the dancer had worked on in his native Memphis.

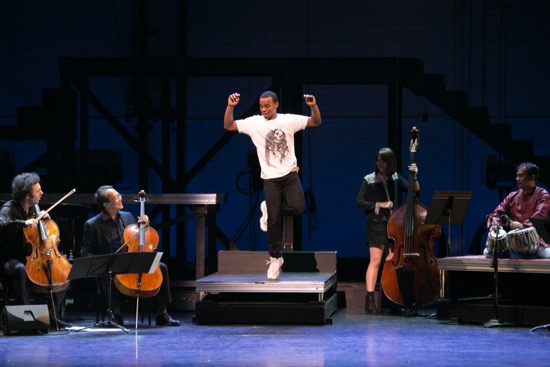

The City Center programs (I saw only the opening one) give a vivid impression of what goes on out in Colorado. Imagine beginning a performance with a production of George Balanchine’s 1928 Apollo that includes the birth of the god and the apotheosis (scenes later excised by Balanchine) and ending the evening with Lil Buck@City Center: A Jookin’ Jam Session. Imagine having two different string quartets perform separately (mostly) on stage with the dancing. Imagine Chinese sheng virtuouso Wu Tong improvising with Indian tabla master Sandeep Das.

And yet, little of this seemed contrived. Woetzel’s spoken introduction and informal program notes set the evening up as an adventure in history and cross-cultural pairings, and the City Center’s opening-night audience received it with delight Certainly 1-2-3-4-5-6 (developed by Michelle Dorrance and Woetzel) was a pièce d’occasion, but how could you not enjoy seeing wizard tapper-choreographer Dorrance joined on her mic’d platform by New York City Ballet’s Robert Fairchild, the two of them hammering out complex rhythms that riffed off those in Steve Reich’s Clapping Music. Add to that Lil Buck gliding around in his sneakers and Melissa Toogood (barefoot, as befits a Merce Cunningham dancer) getting into the act.

George Balanchine’s Apollo. Center: Robert Fairchild. Muses (L to R): Tiler Peck, Isabella Boylston (hidden). and Misa Kuranaga. Photo: Erin Baiano

Herman Cornejo of American Ballet Theatre was sidelined by injury, so Fairchild took over in Apollo, having never performed the opening scene before. Amber Neff of the New Chamber Ballet and Unity Phelan of NYCB were the handmaidens who unwrap him from the swaddling material that binds him, after Leto (Caitlyn Gilliland, last seen in Twyla Tharp’s company) agonized in childbirth atop the tall platform under which Apollo stood in darkness, waiting to be delivered.

One thing I’ve always admired about Fairchild is his focus. He’s always seeing the world he’s in onstage; in this case, he also makes us aware of the empyrean realm from which his father, Zeus, might be watching. Even though Fairchild was new to the original opening scene, he always dances as if he were discovering the movements for the first time. He emphasizes Apollo’s infantile ungainliness, making his steps a little too big, staggering slightly in some of his attempts. He investigates the lyre (looks more like a lute) that the handmaidens bring to him, seeming to listen to the sounds it might make.

Balanchine was initially enthralled by the notion of a fledgling god coming into his power and the three young muses who succor him, compete for his favor, and yield to his command. Many have noted the marvelous ballet’s analogy to his development as a choreographer. Back in 1928, he characterized Calliope as the muse of poetry and rhythm and Polyhymnia as the muse of mime, and realized that he would make use of both, but also realized that Terpsichore, muse of dance and chorus, was the one he loved most, the one who would guide his destiny.

When they enter obediently, Tiler Peck (Terpsichore), Isabella Boylston (Calliope), and Misa Kuranaga (Polyhymnia) seem uncertain as to their attitude to this god-in-training, but they come to life in their solo competitions. Kuranaga is especially charming, confident that she will win, and, of course, Peck and Fairchild perform very beautifully in the remarkable duet to the remarkable Stravinsky score that taught Balanchine so much. It’s lovely to end the ballet not with the famous sunburst of arabesques that announces Apollo’s graduation into the role of sun god, but with the four’s slow procession across the stage and up the tall staircase to Mount Olympus. His mother and her handmaidens enter and fall back in awe. And, as a footnote to this version of Apollo, think how much more Stravinsky music we get to hear, in this case played from the pit by members of the Catalyst Quartet and the FLUX Quartet, plus eight additional musicians, led by Kurt Crowley (currently the Associate Musical Director of Hamilton).

Tiler Peck and Robert Fairchild in George Balanchine’s Divertimento Brillante at Vail Dance Festival: ReMix NYC. Photo: Erin Baiano

Peck and Fairchild, re-garbed in tights and velvet jacket (him) and soft tutu (her) perform Divertimento Brillante, originally danced in Balanchine’s 1967 Glinkaiana by Patricia McBride and Edward Villella and not seen for decades. NYCB pianist Cameron Grant joins member of the Catalyst Quartet onstage. The piece sometimes sounds like party music, often with a ¾ (or 6/8?) rhythm. The prominent piano bubbles and ripples furiously at times (a challenge to which Grant rises wonderfully).

Divertimento Brillante is not a rigidly formal grand pas de deux, although the dancers must display elegant, courteous manners. It’s a vividly choreographed encounter, with the expected happily amorous embraces and lifts, but the two dancers don’t stalk on and off to announce their solo variations. She runs away after her quick-footed dance, as if she has something to do elsewhere, and he bursts on to exalt in leaps and spins; as if hearing him, she hurries back to find him gone. What the hell, she’ll circle the stage by herself until he’s ready for more fun together.

Isabella Boylston and Calvin Royal III in Christopher Wheeldon’s This Bitter Earth. Photo: Erin Baiano

Boylston and fellow ABT dancer Calvin Royal III perform a different kind of pas de deux: Christopher Wheeldon’s This Bitter Earth. (Wheeldon’s short-lived company, Morphoses, made its debut at the Vail Festival in 2007.) I say “different” not because it eschews elegance, but that it is more overtly amorous. Royal not only manipulates Boyleston fluently through some intricate lifts and supports (twice he has to duck beneath her high-aimed arabesque in order to manage her for the next maneuver), he lays his face against her, holds her close, might like to kiss her. Wheeldon has a gift for making virtuosic ballet behavior look intimate. The Catalyst Quartet ( Karla Donahew-Perez, Suliman Tekalli, Paul Laraia, and Karlos Rodriguez) plays the score by Max Richter and Clyde Otis, and Kate Davis sings the lyrics Dinah Washington made famous.

Carla Körbes performing Balanchine’s Élégie in Vail Dance Festival: ReMix NYC. Photo: Erin Baiano

Balanchine must have loved Stravinsky’s Élégie for solo viola; he set dancing to it more than three times. Carla Körbes, who retired from the Pacific Northwest Ballet this past June, dances the solo that he created for his muse, Suzanne Farrell, in 1982, not quite a year before his death. It may not be too fanciful to wonder whether he imagined it as his own lyrical epitaph and she a waiting angel. Körbes performs it in a white gown, with long flowing sleeves, her mane of hair swirling in the wake of the movement. She begins and ends kneeling, making fluid, grieving gestures—bringing her hands to her face, knotting her arms together. When she stands to dance, she seems often to be reaching out into the darkness around her. To the side, in his own light, guest artist Daniel Panner plays his viola, echoing her sorrow.

Vail Dance Festival: ReMix NYC: Sara Mearns in Alexei Ratmansky’s Fandango. At back: (L to R): Scott Borg, Elena Heiss, and Felix Fan of the FLUX Quartet. Photo: Erin Baiano

One of the high points of the opening night program was Sarah Mearns’ performance of Alexei Ratmansky’s Fandango (created for Whelan at Vail in 2010) and set to music by Luigi Boccherini that requires not just the FLUX Quartet (Tom Chiu, Conrad Harris, Felix Fan, and Panner) but guitarist Scott Borg and castanet player Elena Heiss. As Woetzel says in his program note, the atmosphere is that of a village square. Mearns, wearing a lacy costume, by William Ivey Long begins by dancing to the musicians. She also wanders behind them, greeting violinist Chiu with a pat on the shoulder, taking off her shawl and wrapping it around Heiss. She’s not just charming them; she knows that this is a collaboration and keeps that in mind. Still, she slips deeply into her dancing—tempestuous, but controlled, only subtly Spanish (like the music). She’s a marvel as she twists the choreography around herself, flings herself into a leap, and borrows a tambourine from Heiss when she wants a rhythmic boost. A force of nature for sure.

Lil Buck @ City Center: A Jookin’ Jam Session. (L to R): Eric Jacobsen, Yo-Yo Ma, Lil Buck, Kate Davis, and Sandeep Das. Photo: Erin Baiano

Did I mention that this was a very long program? Probably not. Because once the final number starts, almost no one wants to leave. The staircase for Apollo is onstage again, turned the opposite way, and Lil Buck can glide up and down its steps and onto a lower platform with the smoothness of pouring oil. He and his cousin Ron “Prime Tyme” Myles co-choreographed the work with Woetzel. There are unison passages and solo displays in which the two show their mastery at moving across the stage as if their ankles operated on ball bearings. They step on the tips of their toes, on the outsides of their feet, on the insides of their feet; one leg snakes in and out around the other. They mold the air with their hands; they ripple their arms. Now and then you see what might be a jookin’ version of a folk dance or a social dance.

The atmosphere is friendly. The guys rest, slap hands with musicians, get dreamy when the eclectic musical selections do. I’d like to have been a fly on the wall while this jam session was being organized. Kate Davis is on hand to sit at the piano and play-sing a couple of songs. Later I notice her at the back working with a bass viol. At other times, Cristina Pato plays the piano, but she also takes centerstage with her gaita (an Iberian bagpipe). Now Eric Jacobsen plays cello and Grace Park violin. And there’s Das with his tablas and Wu playing not only the powerful sheng with its multiple pipes, but also producing a haunting melody on a Chinese flute and singing in a penetrating, yearning voice. Aaron Copps’ lighting changes the atmosphere skillfully. A couple of other string players saunter onstage and, before that, slinking in as if he’s an undercover agent: Yo-Yo Ma (an opening-night-only treat). There’s a lot of smiling and hugging. A lot of friendly dueling and quiet respect. Does Ma want to play a bit of a Bach Partita? Go ahead, man! (Of course, the jam session is scripted to a degree, and the thirteen or more selections are listed in the program, but still. . . .) Close to the end, Lil Buck performs The Swan and Ma plays Saint-Saëns’ famous piece: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C9jghLeYufQ

Some evening!

Deborah: Love reading your reviews, all of them since you began! Was delighted to see that you’re being awarded a distinction for your writing on dance. So so glad and about time! Martha Hill would be proud.