The Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company presents a trilogy (through November 6th).

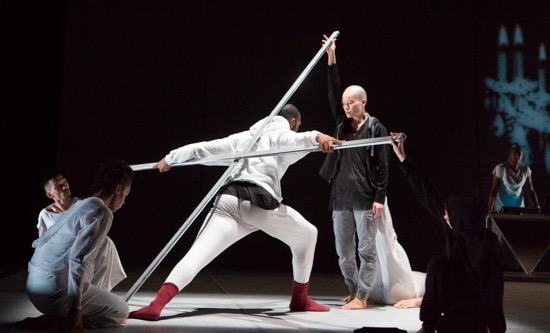

Bill T. Jones’s Lance: Pretty aka The Escape Artist. Talli Jackson (L), Cain Coleman, Jr. (R), and (identifiable front to back) I-Ling Liu, Carlo Antonio Villanueva, Antonio Brown. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Bill T. Jones has always liked to talk on stage—while dancing or when not dancing. Sometimes he wants to get across ideas too complex to be expressed in movement alone; sometimes the movements expresses what was churning beneath the words, and sometimes the words hold the movements in check. Years ago, sitting in an intimate performance place, like the old Dance Theater Workshop, I’d want to slink down in my seat, hoping he wouldn’t turn his gaze on me. But, like everyone else in the performance space, I was mesmerized by him. He was beautiful at being dangerous. Admirable for his anger.

Now the boss of New York Live Arts (the former DTW), he chose to show the first two installments of his The Analogy Trilogy in the nearby Joyce Theater. They need that distance, that aura that a proscenium arch—even one in a modest-sized house like the Joyce—provides. Both new works focus on individuals close to Jones. The first, Lance: Pretty AKA The Escape Artist, centers on Jones’s nephew, Lance T. Briggs, and the second, Dora: Tramontane, concerns the mother of his partner, Bjorn Amelan. Jones constructed the works, basing the spoken text on interviews with the two subjects.

Lance, the only one of the two pieces that I’ve seen, has a tragic story to tell, and many people contributed to bring it to life: Jones; his writing colleague and dramaturge, Adrian Silver; associate artistic director, Janet Wong; composer Nick Hallett; the musicians (recorded or live) who contributed a vivid, patchwork of song, dialogue, and instrumental passages; Sam Crawford, sound design; Björn Amelan, décor; Liz Prince, costume designer; and the wonderfully gifted performers in the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company (who are as adept at talking as he is).

The cross he bears. (L to R): Carlo Antonio Villanueva, Rena Butler, Cain Coleman, Jr., I-Ling Liu, Jenna Riegel (in black), and Antonio Brown. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

And what a life they’ve portrayed. Briggs, aka LTB: promising ballet student in San Francisco, singer, songwriter, stripper, prostitute, paid escort, drag queen, drug addict, traveler, thief, prisoner, cripple (maybe temporarily), and deportee (from London). He is writing his memoir at present. In the program for the event, Jones mentions W.G. Sebald’s The Emigrants as a trigger for him, adding that stories like LBG’s “are rooted in memory, history, and the mysterious force of personality in the face of traumatic events.” Courage and humor can be redemptive.

The piece unfurls in bursts of dancing, often followed by stop-action freezes or tableaux. Dancers intermittently hold microphones and address us directly, or converse across the stage from mic stands on either side. Voices, speaking or singing, also come from the musicians at the side of the theater (Matthew Gamble channels “Lance”). Antonio Brown not only dances, he works as DJTONYMONKEY (his own alter ego) from a console at the back of the stage. The audience hears fifteen songs (or parts of them), six by Briggs or Briggs and Hallett. These range from “This is My Life;” “Bad Boy/Having a Party;” “Work This Pussy;” and “Shame” to Schubert’s “Nachtstück;” and the centuries-old round, “Joan Come Kiss Me Now.” Percussive rhythms emphasize both dancing and drama. In Wong’s projections, Briggs’s many roles and nicknames slide on their sides down the backdrop. A sizeable cot on wheels and a large, moveable, open-sided silver cube convey—among other things—a hospital bed and a jail cell.

Lance: Pretty aka The Escape Artist. Cain Coleman, Jr.(center) and (L to R): Carlo Antonio Villanueva, Antonio Brown, Shane Larson, Talli Jackson, and I-Ling Liu. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The terrific performers wear both ordinary attire and elaborate outfits (costumes by Liz Prince). They strut their way toward the audience or fold down to the floor, as in voguing. They may be expansive, take giant steps, kick the air, or twiddle their feet together when aloft, as precisely as a ballet dancer executing entrechats. But the movement usually conveys struggle, inner pain, or bravado. Once, Talli Jackson (as Briggs) seems to be tying himself in knots. Once, Jenna Riegel throws herself into an equally disastrous solo. Dancing in this context is martialing energy, putting yourself on display, yielding to uncontrollable forces, sympathizing with others.

The choreography does not literally “express” the stories we hear. Jackson tells of how the boy Lance, selling himself on the street, attempts to reverse the usual roles by turning himself into the predator. What we then see are complicated double duets between a tall man and a smaller person (Jackson and Carlo Antonio Villanueva, Cain Coleman, Jr. and Riegel). As I recall, no dancing at all accompanies Jackson’s prideful tale of another reversal of the usual: Lance’s strip act began with him naked, gradually dressing as he danced. Jumping over and dipping under hand-held silver poles (plus the words “I kept moving) is a way of conveying the unsteadiness and impermanence of the titular hero’s life.

The two personas of Lance T. Briggs: Cain Coleman, Jr. and (aloft) Talli Jackson. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Jones and all involved juggle a host of incidents and memories of those incidents. Many voices speak for and about LTB. “Briggs” talks on a telephone with “Uncle Bill.” The precision with which the compositional elements construct, convey, and reprise aspects of Lance: Pretty AKA The Escape Artist is sometimes at odds with the narrative. It can be frustrating to wonder who is speaking for whom. It was a while before I realized that, yes, Coleman was Jackson’s alter ego, “Pretty” (part of Griggs’s jail name), and that, at times, LTB was conversing with that other self. But even after that, I wasn’t always sure who was who where at a given moment. Certain choices remained a mystery. Why was Riegel garbed throughout in all-black attire, including a hoodie that hid quite a lot of her face? Dressed like that and being the smallest person in the company, she resembles a slightly satanic imp (the kind that perches on your bed when you’re delirious). The men (including Shane Larson) figure as friends, rivals, club goers, etc. What other aspects of Briggs’s life are expressed by the two other women in the cast, Rena Butler and I-Ling Liu? Do I sense a mother? A nurse? Or does gender-at-birth play no part?

Rena Butler supported by I-Ling Liu in Bill T. Jones’s Lance: Pretty aka The Escape Artist

I want to know these individuals better, or in more depth, as they figure in Lance Brigg’s life. Those powerful, versatile performers, Jackson and Coleman, move among the others, become like them, but, for the most part, those others remain vibrant, hard-dancing shadows. That may be why about a half hour before the ninety-some-minute piece ended, I became restless. In retrospect, I think that the fluid quality of the essentially rich, carefully constructed piece may be what Jones was aiming for: experiences unsettled by memory or liquefied by drugs.