American Ballet Theatre presents ballets by Tharp, Lang, and Millepied.

American Ballet Theatre’s Isabella Boylston and Alban Lendorf in Twyla Tharp’s The Brahms-Haydn Variations. Photo: Marty Sohl

Goethe once wrote this: “Music is liquid architecture; architecture is frozen music.” For Havelock Ellis—one of the writers on the arts that Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey found inspiring early in the twentieth century—dance and architecture were the sources on which the visual arts were built. Watching one of American Ballet Theatre’s Lincoln Center programs, this dance-music-architecture trifecta chased around in my mind.

This was the program that opened with a revival of Twyla Tharp’s The Brahms-Haydn Variations (2000), continued with the world premiere of Jessica Lang’s Her Notes, and ended with ABT’s premiere of Benjamin Millepied’s Daphnis and Chloe (created for the Paris Opera Ballet in 2014).

The architecture analogy is weakest in regard to Tharp’s ballet, as staged for ABT by Susan Jones, maybe because no one stays still for long, and building-block architecture is avoided. Want an analogy? Try in-process popcorn. When, in canon, men hoist leaping women high, the image of kernels hitting a hot skillet is not entirely untoward. To the orchestral version of Johannes Brahms’s Variations on a Theme by Haydn, waves of people rush onto the stage, rush off again; symmetrical formations yield to asymmetrical ones, sometimes in surprising ways. Classicism is both honored and tweaked. Gallant classical-ballet manners prevail, but people may enter unannounced in the middle of someone else’s major moment and start their own little fire of dancing. There are often people in the background working out their relationship to Haydn, while others prefer the limelight. No tutus, of course, elegantly cut outfits by Santo Loquasto in shades of white, cream, and beige.

You can, if you like, track certain movements as they persist through the variations (holding one curved arm high is an example). Better you should learn to distinguish between the three splendid principal couples (at this performance, Isabella Boylston and Alban Lendorf, Skylar Brandt and Arron Scott, and Gillian Murphy and Marcelo Gomes). Then there are Christine Shevchenko and Joseph Gorak, Sarah Lane and Craig Salstein. In slightly smaller print: Cassandra Trenary and Blaine Hoven, Luciana Paris and Roman Zhurban. You’re always too slow on the uptake (wait! where did he come from?). The corps de ballet consists of eight men and eight women. How’s your multiplication?

Forget the popcorn and think vacuum cleaner—a powerful one that can suck dancers on and off the stage. The heroic and very smart dancers are none the worse for it; they arrive and depart in perfect formation and full of zest. Occasionally the stage is empty at the finish of a variation, and you can hardly wait to see what happens next. Murphy and Gomes perform a tender duet; tender, because amid the expected supported turns and lifts, he hugs her tight, bends her back, and lays his cheek on her breast, and because they often seem about to kiss. The two of them are there when a terrifically fast variation begins and turns them playful; she exits the stage so quickly that he’s grabbing air as he pursues her.

Gillian Murphy and cast members of Jessica Lang’s Her Notes. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

The architecture for Jessica Lang’s Her Notes comes primarily from the choreographer’s set design and Nicole Pearce’s lighting, but the music (piano soloist: Emily Wong) affects it too. This ballet for ten dancers is set to five selections from Fanny Hensel’s Das Jahr: January, February, June, December, and a postlude. Hensel was born Fanny Mendelssohn, Felix’s older sister; a highly skilled pianist like her brother, and the composer of 460 works for piano. However, having been born a woman in the early 19th century, she was from the start made aware what kind of life she was to lead. Her father decreed her role to be that a devoted wife and mother. She performed as a pianist in public only once, although music-lovers knew her worth from regular Sunday afternoon concerts in the Mendelssohn home. Her brother published some of her compositions for piano or piano and voice under his name. Fortunately, her husband, a moderately successful painter (mainly portraits) made no fuss when she began toward the end of her life to publish some of her works. He illustrated and wrote poems on the varicolored pieces of paper on which she wrote the score for Das Jahre, the year (1846) before her sudden premature death from a stroke.

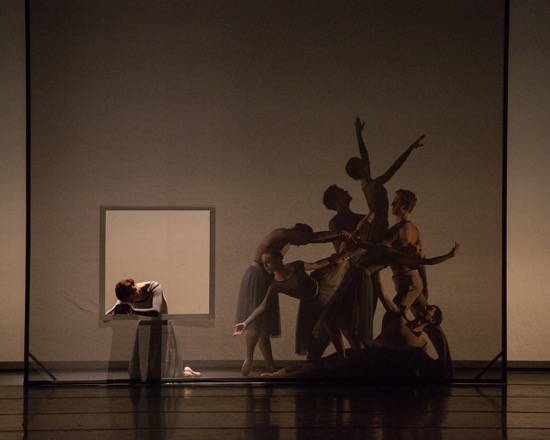

These facts are relevant, I think, to Lang’s ballet (her first for ABT, although a ballet of hers was performed by the company, and she created several for its Studio Company). At one point in Her Notes, part of the remarkable set, a scrim with a square opening like a low window (set within a wide, squared-off arch in a stage-filling backdrop), is tilted by several of the dancers into a horizontal position. Murphy, the obvious heroine of the ballet, is left standing within its opening, as if it were a confining costume, or confining customs. At another time, when the scrim is vertical, she leans out of the “window,” while in the gloom behind the scrim, seven dancers form a silhouetted sculptural tableau, with one woman, lifted, reaching upward.

Gomes is again her partner. When she leads her girlfriends into the light, and the men join them, we can note Bradon McDonald’s pale, attractive, fluid costumes. Perhaps to match Hensel’s rippling, tempestuous winter music, Lang makes lavish use of the dancers’ torsos. They seem to bend their way into and out of the steps. Pearce lights the rearmost backdrop green for hopeful “February,” in which Misty Copeland and Jeffrey Cirio dance together, with Skylar Brandt, Trenary, Cory Stearns, and Hoven as their companions. The section ends with a sly nod to female strength; the men lift their partners high, but Copeland lifts Cirio, then drops him before hastening away.

Gillian Murphy and Marcelo Gomes in Jessica Lang’s Her Notes. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

The backdrop is blue for “June,” the only summer month among the extracts from Hensel’s music, and the scrim with the window is lifted for a sweet duet between Gomes and Murphy. He also dances briefly with Devon Teuscher and Stephanie Williams, before Stearns and Hoven arrive to make companionable trios and affectionate duets with them. There’s an odd moment in which one of the women (was it Murphy?) is set down on the floor to watch, disconsolate, others dance. There’s another curious moment with Murphy and three fallen men. But when the backdrop with the square opening lifts out of sight, she’s alone with Gomes.

There are other strange images in the “December” section. The small “window” glows, and the lighting turns slightly eerie. Once we might be seeing a death and a mourner—Gomes laid out, Murphy kneeling beside him (this came and disappeared so swiftly that I could be mistaken). In this scene, the “walls” descend again, and Teuscher and Williams, two sprightly women, have a moment of girlish confidence in the Postlude before the scrim tilts, imprisoning Murphy briefly. In the end, her only prison is a spotlight, and the scrim is equivocally slanted.

I’d like to see Her Notes again. I haven’t grasped it fully. The images suggest a greatly gifted woman, her family circle, and her friends, as well as the music she is trained to play and to create and the strictures that keep her off the concert stage. The architecture moves in response to her mood.

Benjamin Millepied has always been, it seems to me, a keen architect as far as ballet is concerned. He is adept at devising clean-lined structures that stay with you as dancers move within them. In his Daphnis and Chloe, for example, there’s a passage in which men link arms at shoulder height, turning themselves into a fence; in every opening between the men, women grasp those arms and dip beneath them and back. Sometimes these structures are expressive as well.

Another architectural feature has a field day in Daphnis and Chloe, and this I admire far less. A big production for the Paris Opera obviously needs a set, and Millepied, preparing for a certain degree of abstraction in getting a story across, can’t have been expected to set his ballet in a painted grove. Instead the French artist, Daniel Buren, who is famed for his installations, has combined his interest in vertical stripes with his interest in translucent colored panes to create a series of very large suspended ones in bright hues and a variety of shapes and sizes: round, square, rectangular. These have black-and-white striped borders and, in the case of a circular yellow pane, create an optical illusion; we might be seeing a tilted circus arena with low, striped walls.

These objects appear and disappear, congregate, tilt. One of them (a projection) grows and shrinks. I couldn’t tell whether their behavior relates to elements of the ballet’s plot. And after a while, despite their visual appeal as art works, I began to see them as big, unruly animals and wished I could yell “shoo!” and have them lumber off.

Pan’s nymphs in Benjamin Millepied’s Daphnis and Chloe. Photo: Marty Sohl

This is the most ambitious work of Millepied’s that I’ve seen. It has been staged by former New York City Ballet dancers Janie Taylor and Sebastien Marcovici (the latter now a ballet master for Millepied’s L.A. Dance Project), and ABT dancers take to it with aplomb. The powerfully dramatic music, with its occasional stirring choral passages, was written by Maurice Ravel for the Daphnis and Chloe that Mikhail Fokine choreographed for Serge Diaghilev’s Les Ballets Russes in 1912. Frederick Ashton created his version for Britain’s Royal Ballet in 1951 (Millepied’a arm-linked lines I mentioned above may have been inspired by Ashton’s folk dances).

The characters are clearly defined. Daphnis (Stearns in the cast I saw) loves Chloe (Stella Abrera), but is not quite committed to her. He finds Lycenion (Trenary) very attractive, and Dorcon (Hoven), who has some kind of relationship with Lycenion, evidently craves Chloe. So does the pirate Bryaxis (James Whiteside), who has his men kidnap her.

It’s difficult for a choreographer to make clear these complications, and Millepied does it pretty well. The performers reward him. It’s a pleasant surprise to see Hoven as the mean-tempered Dorcon whip off a mean-tempered solo made up of jagged, extremely interesting steps and to enjoy Whiteside as an unshaven bully, who likes to consider women his rightful plunder. Abrera’s Chloe is a bit weepy, but she knows what man she doesn’t want and is prepared to make that clear. Stearns, as might be expected, is brave and noble, even if he is easily tempted by the sly Lycenion (well rendered with faux-naive charm by Trenary). His first solo is a beauty, with big, exalted suspensions, as if he were taking a breath of fragrant air.

What’s less clear is the atmosphere. Come on, where are we? Not in an apparent woodland where Pan makes the final decision. And not in a church whose stained glass windows are having a party. The onstage folks occasionally cluster, which tells us they are a society. We don’t need wine jugs and garlands and shepherds’ crooks, but it would be nice to have a more cohesive vision of landscape for this ancient Greek pastoral.

You wonder why the people (there’s an ensemble of eighteen all told) shun Dorcon and shove him away. Has he committed a sin beyond flirting with Chloe? It’s clear that Lycenian is his kind of girl (or may turn out to be), although he initially rebuffs her after his solitary temper fit. Suddenly, men in black appear out of nowhere (maybe pirates study to be able to do this), and carry Chloe away, beating up Daphnis when he struggles with them (one of them even spits on him after they’ve left him unconscious on the floor). Bryaxis/Whiteside eggs on the kidnapping with killer fouetté spins.

A cadre of women in white dresses arrives, and, this being a ballet, none of them notices Daphnis lying bruised and bloody until they’ve finished their lyrical dance. Daphnis is weak, but he’ll be all right. I don’t remember these nymphs intervening in the various amorous problems, and I’m sure I didn’t see their master, Pan, but Daphnis and Chloe lived happily ever after.

I write this way to emphasize a certain dramaturgical confusion, but Millepied created, as usual, some terrific passages of dancing. He’s expert now at turning a phrase of movement in interesting directions—not being unnecessarily tricky, but making changes of dynamic or shape look fluid or temperamental or celebratory—whatever is needed. And the dancers performed their roles with nuance as well as passion. And while the architecture of the plot is slightly unstable, the architecture of the dances is solid and very fine to look at.

I’m with you totally Deborah, about Daphnis and Chloe, except that I feel even more strongly that the sets are a total disaster, and have absolutely nothing to do with the choreography. The projections onto the striped curtain during the overture were especially pointless and annoying. The costumes were fine, except for the garish colors of the final celebratory dances, and the hit-you-on-the head impression when the pirates rush onstage: “Here come the bad guys – they are in black!”.

I remember vaguely Ashton’s “Daphnis” for the Royal Ballet and thought its ancient Greek landscape fine. Also that Pan is the deus ex machine who restores Chloe to Daphnis, after she gets Bryaxis drunk in order to escape? I missed the presence of Pan in Millepied’s ballet.

I also agree with you that Brahms/Haydn is too rushed to be really enjoyable. So many people! So many entrances and exits! So many lifts!

I always enjoy reading your wonderfully descriptive reviews, even of performances I haven’t seen.