Colleen Thomas Dance performs a site-specific work on Governors Island, September 16-18.

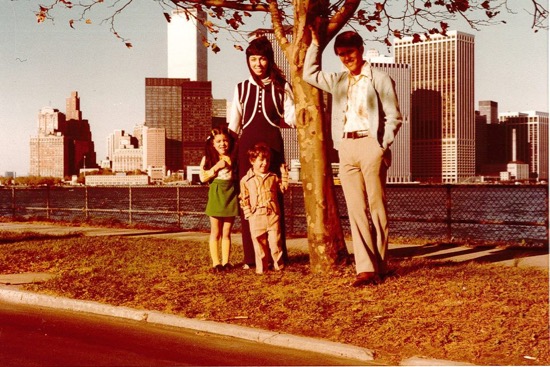

Colleen Thomas (green skirt) and her family on Governors Island in the 1970s

Visiting Governors Island for the first time (yes, really), I look at the fine old wooden houses ranged around the grassy expanse known as Nolan Park—some of them quite grand—and wish I could have grown up there. Probably not when its cannons, facing the scant 800 yards of water that separate the island from Manhattan, hammered away during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. No, I see myself there between 1966 and 1996 when it was a Coast Guard base, and officers lived in those houses with their families.

Choreographer Colleen Thomas had that privilege. Between 1973 and 1978, her father, Jim Stephens, served as a Public Affairs Officer with the Coast Guard, and she and her brother romped over that turf to play or attend school. They didn’t live in the house where she has been presenting her Welcome Home, but in a brick building behind it. So she has transplanted her childhood memories from the 1970s into a now-vacant, two-story yellow house with a front porch and a fireplace in almost every room. Home movies of family life play on a vintage yellow television set in what must have been the parlor. Films and slides also show on two monitors in the kitchen’s open fridge, and one snakes around the hall walls via a hand-held projector (video design: Jason Akira Somma). Photos hang on the walls. One of Thomas; her husband, choreographer Bill Young; and their offspring (Olivia, 10, and Dylan, 5) duplicates one from the 1970s of her parents; her brother, Dean; and her. Both images were taken in front of the same tree, with Manhattan in the background. Only now the tree trunk has almost doubled in diameter.

Three generations in Welcome Home. From the top: Kathy Stephens, Colleen Thomas, and Olivia Young. Photo: Julia Discenza

In one way or another, members of the Stephens and Young families participate in this collection of memories brought to dancing life. Dylan Young sells lemonade on the porch for 5¢ a Dixie cup. Jim Stephens hosts a display of small images upstairs in a tiny back room (once an office perhaps). And the first sight the audience sees when entering the front hall are the three females of the family sitting on the steep narrow staircase that leads to the floor above—Thomas’s mother, Kathy Stephens, at the top; Thomas halfway down; and her daughter, Olivia, near the bottom. They move in quiet unison—lifting their arms and opening them, twisting their bodies. The sweet scene gives a hint of what’s to come.

I saw Welcome Home at its final dress rehearsal, when the audience numbered only three or four, and three photographers were at work, so my experience may differ slightly from that of the spectators (twenty at a time) who will wend their way through the house during a performance. They, like us, may be handed tiny flashlights when they have to climb the narrow winding stairs from the kitchen. And they, too, will feel, I’m sure, that the fairly small rooms often seem about to burst from the energy of the dancers—rumpusing as children and teenagers, and dreaming of what it means to be a grownup.

Samantha Allen dancing in an upstairs room. Photo: Julia Discenza

This isn’t a play. No literal dramas develop. John McGrew’s music and his sound design incorporating pop music of the ‘70s and family voices help build an atmosphere. Elvis makes an appearance— not only vocally, but in the form of an almost life-sized cardboard cutout that’s pulled lovingly out of a closet by dancer Samantha Allen in a room whose floor is strewn with white underpants. Remember Peggy Lee singing Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “I enjoy being a girl”? Those lines that we hear, such as “I’m strictly a female female,” could still resonate and be argued about by Thomas and her friends more than a decade after they were written. Allen, taking off her shirt and jeans in an upstairs room to don heels, a flowery dress, a sleeveless fake fur vest, and shades, brings to mind a little girl edging toward teendom, and the baby blue plastic microphone and stand that she clutches convincingly cinch the image, while Thomas and Darrin Wright dance their rock ‘n roll hearts out.

Guys at play: Oluwdanilare (Dare) Ayorinde (L) and Pedro Osorio hoist Darrin Wright in Colleen Thomas’s Welcome Home. Photo: Julia Discenza

There are some mysteries in Welcome Home, and I think that’s a good thing. Who hasn’t looked at a long-ago family photo and wondered things like, “Who was the guy in the cap?” Or “What was Aunt Ella doing there?” In one upstairs room, Saradiane (Sadi) Mosko and Keith Johnson simmer around behind a white net sheet strung across the room. Together in the confined space, they’re alone in their dancing, their movements loose and free, yet somehow argumentative too. In a wildly impulsive acrobatic game in what must have been the dining room, Oluwdamilare (Dare) Ayorinde, Pedro Osorio, and Wright career around, while Johnson, looking intimidated, huddles on a mammoth, vividly patterned beanbag chair (fetched from the Stephens’ attic). Eventually the others are vaulting over him and knocking into him. Maybe they’re kids with energy to burn; maybe they’re young seamen—since they several times show up left-right-lefting around the house, both outside and inside. In the very dark pantry, Jessica Stroh jerks miserably (?) around on the floor, while Allen perches on a counter and watches.

School days and girl scouts are hinted at. A gathering in the dining room cleverly collages (“stirs up” might be a better verb) a host of youthful events. Look hard, and you’ll see a girl dragging on her first cigarette, while others indulge in swordplay (the weapons, like the cigarette, invisible) or explode into judo moves or fall to the floor. Wright turns his fingers into a bull’s horns, or his arms and hands into alligator jaws, and attacks (most ignore him). A later let’s-play-cowboys vignette upstairs evokes the clichés of endless movies (as when the guy presumed dead sits up and shoots the shooter). It’s admirable that none of these splendid dancers pretends to be a child or a teenager; they all simply perform whatever Thomas has designed with great skill, humor, and serious fervor.

Saradiane (Sadi) Mosko (L) and Jessica Stroh in Welcome Home. Photo: Julia Discenza

If I’ve led you to believe that there’s more pantomime than dancing in Welcome Home, that’s not true. Dance powers all the encounters and the individual explosions—flung out and fierce, say, when Ayorinde has a room to himself for a few minutes, more precise when Stroh and Mosko, legs wide apart, jog from side to side as tautly as racers waiting for the starting gun. The women practice sexy steps. Wright and Thomas pair up, jitterbug style. And, in the end, after Jim Stephens has summoned us down from the room with the Elvis cutout, the whole cast (including Bill Young) assembles in a long diagonal for a line dance before breaking into Saturday-night celebration.

Moving through the site and coming upon these boiling-up activities and more, you are always a spectator on a subtly guided tour, but history seeps in as you climb the house’s stairs, step on its polished floors, look up at the peeling paint on its walls, pause to read what’s scribbled on the hall blackboard, or notice the plethora of spider plants and the macramé hanging. The piece and the structure that houses it are like a palimpsest, but one in which the present reality and what might be behind it are both true and, in part, fiction.

The moment at which being and remembering and stepping (sort of) into someone else’s shoes hits me most powerfully occurs in one seconds-long moment. We’re in the little chamber dubbed “history room,” and Thomas’s father tells us that the building where the family actually lived can be seen out the window he points to. I walk over to the window, and there on the lawn below is Osorio. Perhaps he’s on his way to that other structure. He smiles and waves to me, and I wave back. So long, see you later. Suddenly, I’m in someone else’s life—or Thomas’s artful recollection of something that might have happened. Or of something like something that did happen. Generations ago.

The cast of Welcome Home takes a bow. (L to R): Jessica Stroh, Saradiane (Sadi) Mosko, Oluwdamilare (Dare) Ayorinde, Bill Young, Keith Johnson, Samantha Allen, Darrin Wright, Pedro Osorio, Kathy Stephens, Olivia Young, and Colleen Thomas. Photo: Julia Discenza

I would like to see this; unfortunately I’m too far away. Not only does Deborah’s review intrigue me, but I was on Governor’s Island a year ago June to see Rachel Tess’s site specific work, in a very different part of the park, namely in the Ft. Jay Magazine, where munitions were once stored. Audience was 20 people at a time, and moved around the space, sometimes led by the two dancers holding lanterns. The title of the piece is Souvenir Undone. So there are similarities between them. And many many differences I’m sure as well, as this review clearly indicates. Thank you Deborah.

Sounds like it was a very nostalgic, historical piece.. I would have loved to have seen the 3 generations of Stephens performing together!

Colleen, loved the review, so sorry I couldn’t make it there. Congratulations on your successful trip home. For a family who moved every three or four years it is wonderful when you can truly claim one as home base.