Twyla Tharp presents one new creation and two golden oldies at the Joyce.

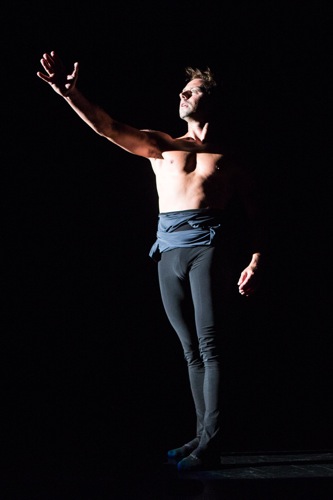

Reed Tankersley in the first half of Twyla Tharp’s Brahms Paganini. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Watching Reed Tankersley perform the long opening solo in Twyla Tharp’s 1980 Brahms Paganini confirmed my sense that Tharp considers dancers as heroes. In this work, which closes the program at the Joyce Theater billed as “Twyla Tharp and Three Dances,” Tankersley, alone onstage, performs Book I (a theme and fourteen variations) of Johannes Brahms’s Variations on a Theme By Paganini, Op. 35, for solo piano (in this case, a recording made for Tharp’s company in 1982 by Kevin McGinty).

It’s not just the sense of ordeal that colors Tankersley heroic, it’s the way Tharp constructs the rarely pausing current of dancing. The choreographic rhythms ride the music as if the performer were designing an intricate, carefully plotted journey—sometimes sauntering along a stretch of the trail, sometimes racing up a hill or launching himself off a cliff.

In deference to the music’s structure and the era in which it was composed, Tharp has created movements that keep the dancer’s feet as precise and busy as any ballet soloist’s and send his legs into clear-edged positions in the air. Yet his arms often swing free and his hips, upper body, and head enter into slippery conversations with one another. Because the music varies its theme, the choreography revisits movements in new surroundings, chopped apart, re-ordered, altered in speed, performed in retrograde, turned upside down—in other words, beset by all the strategies Tharp can come up with.

It occurs to me that if a dancer were to perform a section of this by giving every movement equal weight and performing all of them in an even, moderate tempo, we would soon tire of watching, no matter how interesting the choreography; it’d be like listening to someone delivering a speech in a monotone. Instead Tankersley sinks luxuriantly into a step, pounces on another; hovers over his dancing; dives, shrugs, wrenches, or wriggles into it; Tharp is a master of dynamics. One of her favorite tactics is to have a dancer suspend a balance on one leg for a long intake of breath and follow it up with a spatter of fast footwork. Tankersley, performing the solo splendidly, follows in the footsteps of Richard Colton and William Whitener (its original performers). Like Colton, he is a smallish, compact man, and his fluidity is a constant surprise. He dances as if he’s living a fine, but not always easy day in his life and taking pleasure where he finds it.

(L to R) Nicholas Coppula, Amy Ruggiero, and Daniel Baker in Brahms Paganini. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

For Brahms’s Book II (fourteen more variations), Tankersley yields the stage to four other terrific dancers (Daniel Baker, Nicholas Coppula, Ramona Kelley, and Amy Ruggiero), who are often paired in this section. And they are daredevils. The collisions and elaborate tangles also point up their daily heroism. The women may be swung into the air or snatched up, but they’re hardly fragile (even though the disconcerting ending has them held upside down by the men as the lights go out).

When I first wrote about Brahms Paganini in 1980, I noted an irony: “. . .it is through cooperativeness and consideration and skill, which have to figure in any dance this difficult, that this work creates an illusion of debating, fighting, yielding, winning, and turning to enter a new competition.”

There’s a mystery woman in the second half of Brahms Paganini. Kaitlin Gilliland, dressed in white (costumes by Ralph Lauren), twice enters for a few brief moments and exits into the nearby wing from which she entered. On her third visit, she stays to perform a slow solo that refers to some of the moves in Tankersley’s beautiful ordeal. I suspect that she’s no one’s ghostly love—just a strategic reminder of a strain of music that we have forgotten. It’s the sort of idea that might have occurred to Tharp’s phantom mentor, George Balanchine.

Kaitlyn Gilliland in Brahms Paganini. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The program opened with Country Dances, a 1976 work that began its life as material for cinematic trickery in Tharp’s PBS special Making Television Dance. Santo Loquasto designed the delicious costumes to look more wildly motley than anything to appear at a hoedown, but Tharp used vintage tunes recorded by The Hired Hands, The Kessinger Brothers, The Skillet Lickers, Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers, and Johnny and Albert Crockett. Fancy guitar and banjo picking, along with raucous nasal voices, rule this probably liquor-laced get-together. The songs have such names as “Rat Cheese Under the Hill” and “Cacklin’ Hen And A Rooster Too.”

John Selya catches Amy Ruggiero in Tharp’s Country Dances. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

There’s only one guy in this foursome (John Selya), and he’s full of beans, the rooster in the henhouse, ready to dance and play games with Eva Trapp, Ruggiero, and Gilliland. He’s also watchful: what’ll this woman do next (especially Gilliland, who twice runs her nose up his chest)? When those women swing their hips or fling up a leg, their skirts fly (even Ruggiero’s tiny flounce). They push each other, tangle, dive into (they hope) waiting arms, confer, sneak, stagger, and squabble. They balance, slow-motion, against a jitter of music.

The four may make me think of a cock and his cohort, but then, so do some of the moves in country dancing: the strutting, the flapping elbows, the skittering, the flurries of activity. They swing their way a grand-right-and-left and slip out of it before it’s fully hatched. One motif stands out. At various times, two will leave together, arm-in-arm or just conspiratorially close—off to have a chat or a drink. These four people give the impression that what we see onstage is their own little party, away from the main hall.

Kaitlyn Gilliland (L) and Eva Trapp confer in Country Dances. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

These days, Tharp dancers sometimes strike me as too aware of the audience, but in this piece, their camaraderie and detailed reactions to one another seem spontaneous and real in terms of the context. You can see that behavior too in a short, black-and-white video clip of the original cast (http://www.twylatharp.org/content/country-dances) Click on “video” to see Tom Rawe, Christine Uchida, Shelley Washington, and Jennifer Way in action.

If Country Dances leaves you smiling, Beethoven Opus 130 wipes that smile right off your face. This is the piece that, bookended by Country Dances and Brahms Paganini, premiered just weeks ago at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center. It left me wondering what was going on in Beethoven’s life during the year (1825) in which he was writing this great, tumultuous string quartet (ill health, deafness, and other problems plagued him, and he died two years later). Or what Tharp, who just turned 75, is brooding about in her late years. Most likely, however, she was impelled by things she hears in the music—its storms, its dissonances, its changes of tone, its challenged melodies. The lighting that Steven Terry provides is unlike Jennifer Tipton’s subtle designs for the two earlier works on the program. It changes without warning, dims, tinges everything with a sunset glow, slants in from a different direction.

Despite the piece’s title, Tharp uses only two movements of the six that comprise Beethoven’s quartet no. 13: the second (“Presto”) and the fourth (“Alla danza tedesca: allegro assai”). The composer’s Grosse Fugue, Op. 133 takes up the last fifteen minutes of her work. Grosse Fugue, Beethoven’s original ending to what was a very long quartet, pleased neither the public nor the critics, and he wrote a shorter ending, mollified by having the torrential double fugue published later with its own opus number (133). Any sweetness or peacefulness the music contains arises tentatively out of instrumental struggle and carefully plotted strife.

Kaitlyn Gilliland and Matthew Dibble in Twyla Tharp’s Beethoven Opus 130. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The movements that Tharp devised to this recording by the Talich Quartet come closer to those dances that she made for ballet companies than those that have a more rumpusy vernacular twang. In the beginning—amid the individual rushings in and out by six of the eight dancers wearing Norma Kamali’s dark-hued costumes (Baker, Kelley, Ruggiero, Trapp, Coppula, and Tankersley)—Matthew Dibble whips off multiple spins “a la seconde” and Gilliland succeeds him with a few fouettés of her own.

My musings about the music’s origins were prompted by the mysteries in this beautiful, disturbing work. Dibble becomes the protagonist, wandering in, often pausing to reach toward something unseen offstage and slightly skyward. Gilliland, wearing a long, dark, translucent gown, is taller than Dibble and can make him smile; she also seems to dominate him. Not only that, she sometimes curves her long spine and comes at him aggressively or churns the air around him with her long, long legs. Is she a muse? An elusive beloved? Coppula—having slipped out of the top half of Kamali’s ingeniously designed costume and knotted the sleeves around his waist—crawls onstage, forehead to the ground, and Gilliland steps over him in various ambiguous ways, while, alone at the back of the stage, Baker dances fiercely.

Matthew Dibble in the last moments of Beethoven Opus 130. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Coppula and Gilliland move together in suddenly bright light amid others (as I recall, Baker, Kelley, and Ruggiero) on other business. At some point, she pushes him away, Dibble arrives, again reaching toward what only he can see, and Baker pushes Gilliland offstage, leaving Dibble, a wonderfully eloquent dancer, to unspool his thoughts—slowly and intricately— in near darkness.

Sometimes various of the others also reach for what you assume is unattainable, and the piece becomes something of a puzzle. Why does Baker give Kelley a swat on the butt before leaving with her?.Why does Gilliland cover her mouth with her hands after grabbing Dibble and hurling him to the floor—is she stifling a laugh, and is this a game? In one arresting moment, Dibble, motionless and alone onstage, stares at his hands as if he’s never seen them before, slowly lifting them in front of him. Then the lighting turns the stage dangerous, and as other cross the stage and disappear, he watches them as if welcoming his phantoms, or bidding them goodbye. Yet such encounters and alliances occur within immaculate formal passages, such as one in which the other men (including Tankersley) dance in unison behind Dibble or the cast forms parallel lines. All while Beethoven storms on.

Near the end, Dibble pulls the top of his costume down and, as Coppula did earlier, crawls along. Others help him to rise before they dance out of his life. He’s left alone in a small beam of light and in silence. Is that how we all finish?

Forget that for now. Think instead of the glory of these dancers and the brilliance of this unpredictable, greatly gifted choreographer.

Wonderfully detailed review of a clearly important event. Wish I could have seen the Beethoven. I like your use of the term “heroic” . I agree — that there is something of that quality in many of her works — and it has to do with the ceaseless flow of highspeed movement absolutely packed with intricate detail. Only supermen and superwomen can perform. them. (For me it resonates with Balanchine talking about his dancers as byzantine “angels”, but not the soft, sweet cherubic kind — more like angel-warriors that are above human emotion.) Sometimes Tharp’s movement, unlike Balanchine’s, feels incredibly “driven” to me — the pressure continually building and the viewer as well as the dancer never allowed any respite. I always think her work has to be seen again and again to really catch the intricacies and subtleties of her work, and at the same time keep up to speed with the momentum. That is not quite as clear as I would like it to be, but your review was a model of clarity. . .

Thanks for this beautifully speculative account. I suspect the Beethoven looked somewhat clearer at the Joyce than it did at SPAC, where the dim lighting made some of the movement unintelligible. Although, as you say, it’s among her more purely ballet pieces, it’s more interesting than most of her other works of that sort–certainly than her other Beethoven piece, the 7th for NYCB. I found Gilliland & Dibble’s mismatch in height problematic, since it tended to muddle the tone by suggesting comedy (as in the opening movement of Balanchine’s Bourree Fantasque), although nothing comic was happening. Your suggestion that Gilliland might be a symbolic figure helps a bit, though I’m not sure it’s really the solution, Brahms Paganini is quite wonderful & I was delighted to discover it. It comes from that really great period when she’s gearing up to do The Catherine Wheel–which BP’s exuberance reminds me of.