Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s Lincoln Center season (6/8-19)

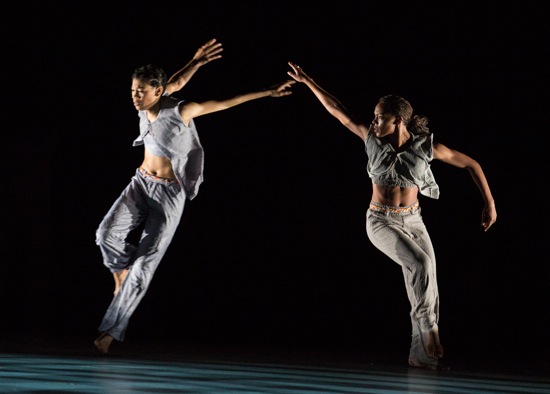

AAADT’s Ghrai DeVore (R) and Samantha Figgins in Kyle Abraham’s Untitled America: Second Movement. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

What’s going on here? I exit onto the Lincoln Center Plaza after watching “21st Century Voices” one of the five programs that make up the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s season at the former New York State Theater. Although I’ve seen plenty of spiritual aspiration and yearning toward the light, I haven’t noticed many flouncing skirts; sassy struts; men stalking women, smooth as snakes; and eye-catching displays of virtuosity. There were no tried-and-true masterworks, such as Ailey’s Revelations and Blues Suite, on this particular program. Paul Taylor’s steamy Piazzola Caldera appeared on the “Dance Trailblazers” program, along with Deep, a premiere by Mauro Bigonzetti, and Revelations.

In putting works by Ronald K. Brown, Kyle Abraham, Rennie Harris, and Robert Battle together in “21st Century Voices,” Battle, the AAADT’s adventurous artistic director Battle, and associate artistic director Mayazumi Chaya took us, the audience, into intermittently dark places where we could observe not only strikingly individual dancers living in societies that had their share of pleasure and pain, but ones who could also mass to achieve common goals. Spectators clapped and cheered, but not when a dancer’s leg shot up impossibly high.

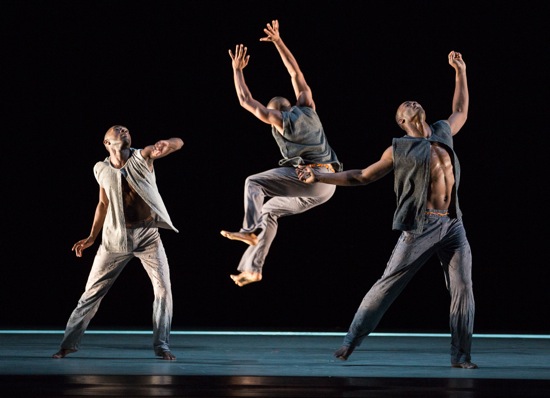

(L to R): Chalvar Monteiro, Michael Jackson, J., and Jamar Roberts. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The premiere on the program was Kyle Abraham’s Untitled America: Second Movement. The first movement of this projected trilogy premiered last year; a trio for two men and a woman, it lasted all of five minutes. The meatier new work is danced by three men and four women, while Sam Crawford’s sound design incorporates spoken words; three edgy, nervy, jangling pieces by Raime; and “No More, My Lord,” one of the black work songs recorded by Alan Lomax on one of his field trips through the American South (in it, you hear the intermittent thwack of —maybe— an axe hitting wood). The dancers (I saw Renaldo Maurice, Yannick Lebrun, Jeroboam Bozeman, Jacqueline Green, Danica Paulos, Jacquelin Harris, and Sarah Daley) enter the stage gradually from the blackness at the back (lighting by Dan Scully). Each of them reaches one palm down to touch the earth in a kind of homage. One man helps another up and then carefully lays him out on the ground.

While the dancers wander, as if in a mist, voices surface. “My sentence was 6 to 12 months.” “I was 21 years old.” Words about wife and family. Periodically three or four such sentences repeat. Loose and strong, the seven terrific performers dance, legs often set widely apart, knees most often bent. Abraham has a rich way of making movement that, however shapely, explodes from an inner heat. The choreography doesn’t acknowledge gender differences, nor do Karen Young’s costumes; men and women alike wear loose pants and vests held closed by a single button (only later in the piece, when they reappear without the vests is it obvious that the women’s breasts have additional covering).

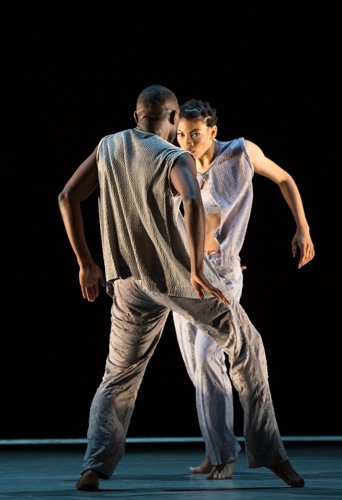

Michael Jackson, Jr. and Ghrai DeVore in Kyle Abraham’s new work. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Images of helping others vie with more violent visions (at least one of which Abraham has used these before in works for his own company). In the midst of dancing that looks like hard, vigorous work, one or more people may crash to the ground and lie there, curled on his/her side, hands seemingly cuffed together. What had begun like a bold dance move ends in catastrophic stillness, even though the fallen rise again.

We also see the dancers in twos or threes or alone. Roberts performs (magnificently) an amazing solo that seems to pit strength against powerlessness. The music ticks and clangs and simmers around them. In the end, for a few seconds, they unite in a tableau. Then, hands again behind their backs, they walk away from us into darkness as the curtain slowly, slowly, slowly descends on their world.

Daniel Harder and AAADT dancers in Robert Battle’s No Longer Silent. Photo: Paul Kolnik

The most surprising work on the program was No Longer Silent, choreographed by Battle in 2007 for Juilliard students. The title refers to the Czech composer Erwin Schuloff (1894-1942), whose cataclysmic 1925 score for a “ballettmysterium,” Ogelala (based on a legend of Pre-Colombian Mexico), was banned when the Nazis invaded his homeland. He died of tuberculosis in a concentration camp. At the Juilliard premiere, the work that Battle set to Schulhoff’s music appeared with premieres by two additional choreographers (Adam Houghland and Nicolo Fonti), set to music by two other forgotten composers of the era.

Some of Battle’s choreography harks back to the massive movement choirs of Rudolf von Laban in the period between the two world wars. A fierce overture sets the tone. In the stunning opening, the dancers, clad identically in black trousers and jackets, are divided into three contrapuntal units. They seem like a horde—more people than the actual head count of eighteen. They huddle and rush, cower and fall, hold their hands up, somersault backward, kneel and perhaps pray at the white fence at the back that resembles a ship’s railing (set by Mimi Lien). Sometimes when they run, they twist their heads to the side—an eerie effect. They lie prone, heaving their hips in the air, as if in accompaniment to brief encounters for several people or outbursts by one. They sit, both their legs and their upper bodies lifted off the floor, and turn their heads to stare at us. Their joinings and re-groupings and circlings can come to feel like waves—racing, forced into other directions, forming riptides.

Once, Nicole Pearce’s lighting creates a narrow, horizontal ribbon of light across the stage. Standing shoulder to shoulder, the performers are invisible, except for their faces—as if they’re looking at us through a long slit of a window. Battle is not telling a story, but he has captured the tempos and images of flight and repression brilliantly. Sometimes in the silences between various of the music’s thirteen sections, the hunched-over dancers’ scurrying feet are heard against the hard floor.

Ronald K. Brown’s Open Door. Center: Jacqueline Green and Yannick Lebrun. Left, front to back: Collin Heyward, Michael Francis McBride, and Jeroboam Bozeman. Right, front to back (visible): Fana Tesfagiorgis and Jacquelin Harris. Photo: Paul Kolnick

Brown’s 2015 Open Door (with choreographic assistance from Arcell Cabuag) and Harris’s 2015 Exodus share a common ingredient in different ways. The dancers in each seek, or are drawn toward a kind of enlightenment or fulfillment, and seeking a common good. Late in Exodus, as in Brown’s earlier Grace, the dancers gradually exit, and when they reappear, they are garbed in white.

This sixth work by Brown for AAADT is set to music by Luis Demetrio, Arturo O’Farrill, and Tito Puente, as recorded by Arturo O’Farrill and the Afro-Latin Jazz Orchestra. It grew out of his visits to Cuba, and you can understand its title ideologically—trips to Cuba now being easier to manage than they once were and America still (despite Trump) open to rest of the world (“your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”). You can also see that “door” literally in a gesture the dancers make of opening it. For the rest, they dig into the hot music joyfully—hips alive, eyes flashing, arms and feet working the air. In my view, Brown overuses big, swirling turns on one leg, but they do help promote the sense of varying dynamics and rhythmic complications typical of his choreography.

Open Door begins quietly with rippling piano music and (in the cast I saw), Jacqueline Green treading what seems like a precarious path across the stage, backing up a bit, and daring to continue. Once “there,” she unfolds into some big, juicy, snatchy dancing. The first performer to replace her onstage (Yannick Lebrun) repeats the movements she established, but they look different when owned by him. Yes, the stage turns into a big party—with organized show-offs for all, encounters for fewer, and passings through by others who may have hotter appointments elsewhere, yet know that, in the end, they all belong here.

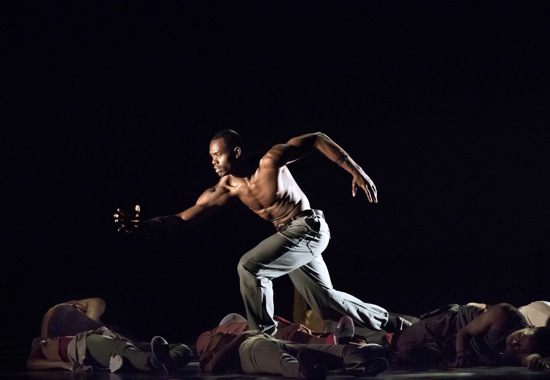

Jamar Roberts in Rennie Harris’s Exodus. Photo: Paul Kolnik

Harris arrived at where he is from his beginnings in and his enduring love for hip-hop culture. What he subsequently learned about other forms of dance broadened his perspective but didn’t change those powerful roots. When he titles his work Exodus, he’s not talking about the second book of the Bible and the expulsion from paradise; he’s talking about people moving away from “ignorance and conformity” as part of a journey toward enlightenment.

In Exodus, you see people falling and being caught, people moving wildly and being stilled, people lifting others, people kneeling. Roberts reaches out to a dejected Renaldo Maurice. But you also see all these people dancing to beat the band—their sneakered feet skittering on the floor so rapidly that you can barely see them. You relish the interplay of speed and slowdowns, the way a hop turns into a triple hop before it moves on to become something else, the interplay between sharpness and seductive rippling. The songs or song fragments speak of harmony: “You may be black, you may be white. . .” (from Jack’s House) and heaven (a fervent deconstruction of “Sweet Chariot,” with an imploring repeated “Carry me!”) But even as more and more of the dancers exchange their idiosyncratic street clothes (by Jon Taylor) for white garments and shoes, and their gestures increasingly reach upward, their feet are wedded to the ground—maybe the hard pavement we tread every day—but, with their stepping, it gets just a bit more resilient.

The AAADT’s 21st-century choreographic voices, wonderfully embodied by its dancers, are not soothing; they’re hopeful, sturdy, ebullient, willing to take risks, considerate of others. Also fierce. These days, in a cruel world, that beats being sweet and heedless and resistant to change.

I look forward, in part because of reading this review, to seeing Ronald K. Brown’s company dance in Portland next season. Also Kyle Abraham’s.

No Revelations! Unheard of. Ailey has come a long way and appears headed in a very good direction under Robert Battle. Thanks for another insightful review with implicit history lesson.

Is there any other information about this subject in other languages?

Why this site don’t have other languages?