American Ballet Theater mounts Alexei Ratmansky’s The Golden Cockerel.

It occasionally happens that a ballet from another era comes to us tangled in its own history, even as it tries to make sense of it. American Ballet Theatre’s production of The Golden Cockerel as re-imagined by Alexei Ratmansky is just such a work—gorgeous to look at, often comical, often perplexing. At the end of the 1820’s, New Yorker Washingon Irving, who’d been knocking around Europe, became entranced by Spain, especially Granada, with its Moorish culture. He wrote Tales from the Alhambra. In Russia, in 1834, Alexander Pushkin wrote a poem, “The Tale of the Golden Cockerel,” based on one of those Irving stories. In 1907, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov composed an opera in inspired by Pushkin’s poem. In 1914, Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes presented the opera as a ballet, Le Coq d’Or; the singers performed offstage, while the dancers mimed the plot and performed Mikhail Fokine’s choreography. In 2012, Ratmansky choreographed for the Royal Danish Ballet a pared-down version to an orchestral arrangement by Yannis Samprovalakis of Rimsky-Korsakov’s score.

The work deals with familiar 19th-century ballet images—a ballerina as a magical bird; a sorcerer-scientist who has created her; a royal person who makes bad judgments; a beautiful, tantalizing seductress who causes kingdoms to fall—and shapes it as an “oriental” fantasy about greed, desire, and downfall. It seems to me, however, that the plot, as it was passed down through various versions, has a fatal flaw: except for a few isolated seconds, you don’t feel sympathy or affection or grief for any of the characters who populate it. The gilded “cockerel” (a female on pointe despite the descriptor) is jerkily mechanical, seemingly without a will of her own. The Queen of Shemakhan is an enigmatic, predatory charmer. The Astrologer, who created the Cockerel to assist Tsar Dodon, who was spending too much of his time sleeping, is determined to keep for himself the Queen who has lured Dodon away from his duties and his scruples. The Tsar’s two boastful, do-nothing sons end up mistakenly skewering each other in battle, and you don’t really mind.

Duncan Lyle as the Astrologer and Skylar Brandt as the Golden Cockerel. Studio shot by Fabrizio Ferri

Occasionally, you feel the frustration of General Polkan, a buffoon of a womanizer whose military advice is seldom taken. Too, as the Tsar flounders among the pillows on his bed, seeking to grasp the Queen, who’s only a dream at that point and slides easily away, you may think, “give the poor guy a break.” (I should point out that the opera, which premiered in Moscow in 1909, was immediately banned in Russia. Given the three major defeats and many losses of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) and outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1905, a doddering Tsar wasn’t a figure likely to be tolerated onstage).

The only character I felt a few pangs for was Amelpha—billed as the Tsar’s Housekeeper, but clearly more than that. She brings the vodka when the higher-ups need to toast before battle and slings back a shot with the men. She slips behind the sleeping Tsar, lolling on his throne, and holds his head erect so that the assembled warriors won’t think badly of him. And she wails like a lover bereft when the Cockerel (whose creator, the Astrologer, the Tsar has killed,) delivers a fatal pecking to the Tsar’s head, and he falls to the floor.

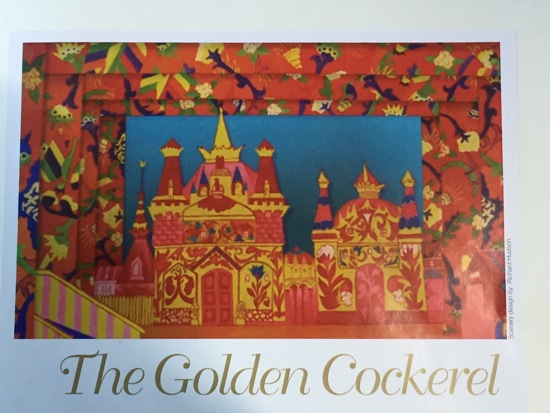

The production, as I said, is gorgeous. Richard Hudson’s set and costumes (originally for the Danes) were inspired by Natalia Goncharova’s designs for Les Ballets Russes. Red, orange, pink, yellow, and bright blue mingle in a combination of sophisticated patterning and folk sturdiness. On the backdrops, minarets crowd gigantic flowers, and the frontcloth shows the characters banqueting, with roustabouts dancing in front of them and musicians playing. There’s hardly a blank space anywhere. The peasant women’s billowing skirts are all different, all almost shockingly vivid. Brad Fields’ lighting brings all this to atmospheric life.

“What’s that I hear?” The peasant women in Act 1 of American Ballet Theatre’s The Golden Cockerel. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Ratmansky’s choreography is vivid too. Each of the princes has a competitive solo that reveals not just dancerly virtuosity, but character traits. The two men in the performance I saw, Alexandre Hammoudi and Arron Scott, managed every snotty boast and cowardly retreat with the same skill they brought to the dancing. I appreciated the small touches, such as Hammoudi’s “wait, you haven’t seen the best part yet,” as he races into some new stunt. There are lively peasant dances by the women in their red Mary Janes. Patrick Frenette, Blaine Hoven, Gabe Stone Shayer, and Simon Wexler excel at the antics required of skomorokhi who roam the country, entertaining with acrobatic or comedic feats and the sound of balalaikas.

The Queen of Shemakhan dances on pointe, of course, and Hee Seo makes every move alluring, whether she is showing off her flexible back or stepping onto pointe and then sinking sensuously into the movement. Rimsky-Korsakov’s music turns “oriental” for her, the “ Persian” handmaids (led by Christine Shevchenko) who copy her, and two male servants (Frenette and Joo Won Ahn) who lift her into beguiling poses. The Tsar forgets his dead sons to follow her into her battlefield tent and then carry her home with him.

Ratmansky gave the gray-bearded Astrologer a particular style. He swoops around, knees bent, hunched over, swiveling to make his shimmering cloak fan out around him. At the June 8th matinee, James Whiteside looked splendidly in character and enacted his lust, his power, and his guile with skill. One of the most difficult roles is that of the semi-helpless, vainglorious Tsar—wanting this, and then not wanting it, having trouble making up his mind about anything. Roman Zhurbin performed with sensitivity all Dodon’s sudden changes of mood. Sarah Lane, strutting on pointe, made the cockerel’s predatory, mechanical choreography glisten—now arching her back, now bending stiffly forward from the hips, now whirring her arms to make her wiry little wings seem to flutter.

Guest artist Gary Chryst as Tsar Dodon confronts the Peasant Women and confuses the Boyars. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Anne Holm-Peyk, who staged the ballet for ABT can be credited, along with the choreographer for bringing out the nuances of character, and stimulating the performers to be alert onstage at all times. Craig Salstein as General Polkan—padded, heavily bearded, and walking in almost a Groucho Marx waddle—seemed never at a loss for business and reactions. Catch him off to one side, going through a kind of inept juggling of the orb and the scepter, in an effort to remind the Tsar of his position and stop him from falling into the Queen’s snare.

In the performance I saw, Amelpha was played by Tatiana Ratmansky, the choreographer’s wife. She’s a bold beauty, and her acting was exemplary—truthful within the onstage fantasy. You felt that she could hold the Tsar’s kingdom together if she had to, even in her humble capacity.

Creating The Golden Cockerel for the Royal Danish Ballet, a company in which he had once performed, Ratmansky knew well how expert those dancers are at acting, and the ABT dancers rise to the challenge excellently. The large part that acting and pantomime play, especially in the long first act, may have its roots in the work’s history as an opera and an opera-ballet. The music was written to fit a plot, and it’s a plot that can’t be revealed through dancing alone. This caused some negative feelings among audience members avid to see virtuosic display, but I think those feelings were due in part to the issue of empathy. Whom could you love in this cauldron of war, rivalry, chicanery, and avarice? Where is a hero to cleave to? Where a heroine?

The Peasant Women of The Golden Cockerel clap hands and dance. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

There’s no happy ending to the story. Nor is there a tragic one. The Astrologer has demanded that the Tsar give him the Queen he believes he has captured in payment for the Cockerel. After all, the bird alerts him when enemy armies are near and (finally!) has guided him to victories that previously eluded him. That wasn’t part of the bargain, contends the Tsar. You know the outcome: two dead bodies.

The Astrologer, however, rises to deliver a gestural epilogue. He tells us that almost all the characters whose drama we’ve just watched are not real—just part of a vision he has concocted. He, however, is real—he and the Queen of Shemakhan, whom he will now pursue to the ends of the earth. As in the beginning, she floats high above his head behind a scrim. And the curtain falls. You want to applaud. You also want to say, “Wait!. . . .WHAT?!!!”

Ratmansky’s new Cockerel is the ABT work I most wanted to see–but travel plans have taken me away during its entire run. Thank you, Deborah, for such a vivid account of its pleasures & pitfalls!

I am grateful to George Dorris for the following comment and for his permission to post it:

“[D]espite what the ABT notes say, the Russian censorship came before the opera was produced, not after – which is why it wasn’t staged until after Rimsky-K’s death. There’s no reason why the Tsar’s own opera house would have staged something that was immediately censored.”