Susan Marshall, Jason Treuting, and Suzanne Bocanegra explore our perception of color.

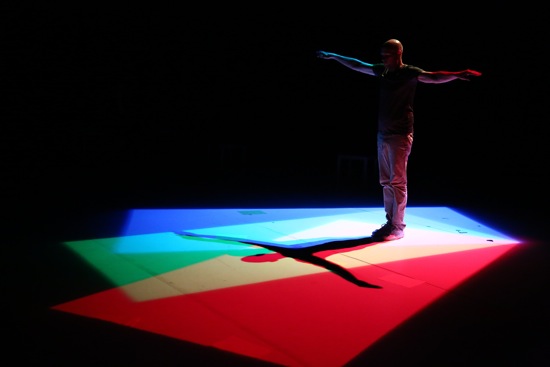

Jason Trouting orchestrating a prism in Chromatic. Photo: Paula Court

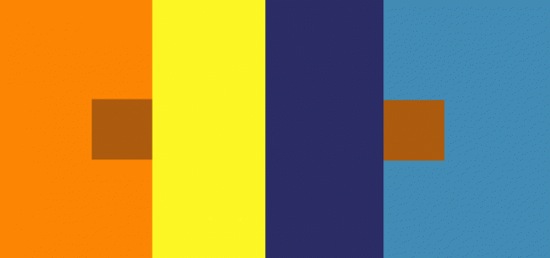

Is this the coolest ever lecture on color theory? Yes and no. It’s also a piece of theater created and performed at the Kitchen (June 23-25) by choreographer Susan Marshall, composer Jacob Treuting, and visual artist Suzanne Bocanegra. However, after seeing their Chromatic and its references to Bauhaus artist Josef Albers’ book Interaction of Color, I got very excited over the found-online vision test below.

Do the two smaller squares seem to be different in terms of color? To our eyes they do. Actually they’re the two ends of a long, slim, solid-color rectangle. The colors with which they are displayed affect how we perceive them.

Is Chromatic a dance? If Marshall’s status as a choreographer and her work’s place on the American Dance Institute’s programs at the Kitchen make it a dance, so be it. In any case, the three performers do move, pose, and make designs in space; in addition, their interactions invariably call attention to their humanness. Take one demonstration of theories relating colors to musical pitches. Marshall and Bocanegra stand side by side, holding up small, colored squares of metal. Treuting races along in front of them, striking each tile with a drumstick as he goes. A brief melody is created. If the women change places or hands, the tune changes. If they open up a larger space between them, a pause is inserted into the rhythm. But this witty musical trick has other implications; the women stand obediently and seriously, while the man displays his speed and precision. Think a magician and his female accomplices. Think a male bird flaunting his feathers.

(L to R): Jason Treuting, drumstick in hand, runs past Susan Marshall (L) and Suzanne Bocanegra and their “instruments.” Photo: Paula Court

The Kitchen’s performance space has become a vivid laboratory. Off to one side, behind a small low table holding equipment for projecting images and I’m not sure what, three heaps of clothing are lined up; one holds predominantly yellow garments, one veers into blues and lavenders, one into varieties of red. Marshall and Treuting seat themselves at a small table that holds two piles of letter-size paper. Side by side, staring straight toward us, they call to mind Grant Woods’ painting “American Gothic.” During the drill they embark on, they focus on that, but also take cues from each other. Marshall’s occasional wry smile suggests private amusement.

The papers are of various colors; the two hold them up, one at a time to show us; sometimes hers are vertical, his horizontal, or the opposite. Eventually they synchronize and also show us smaller different-colored squares against the larger sheets. With Treuting’s foot on the floor signaling changes, the paper exercise builds its variations from both performers passing sheets to the floor on one side, to lobbing them in front and behind themselves as well, to hurling them up in a storm in which we spectators get caught (I came home with two papers in shades of yellow).

Susan Marshall and Jason Treuting managing papers in Chromatic. Photo: Paula Court

Tasks acquire the rhythms of a dance. When the papers littering the floor become a hazard, Treuting and Marshall advance on them and cross the stage urging them into a pile by lashing them in synchrony with big pieces of colorless fabric.

Bocanegra enters wearing a short black dress. In a lively manner, she recounts relevant tidbits from color theory and its history and makes sure we hear about and/or see on the back wall the color wheels and charts and notations by Goethe, Albers, Hans Richter, Isaac Newton, William Morris, Mark Rothko, Rudolf Steiner, and others fascinated by color harmony. Who until now had heard of Mary Hallock-Greenewalt (1871-1950) who invented and played a color organ she named Sarabet after her mother and who called her visual music “Nourathar”?

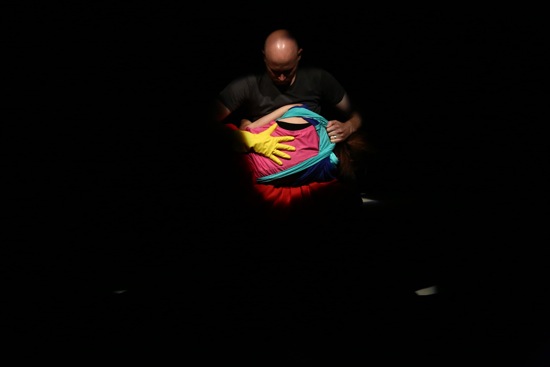

Marshall and Trauting layer on clothing from the heaps while Bocanegra holds forth; since we focus on her and what we’re seeing projected, it’s a surprise when the two start peeling off garments that hint at roles (draped in red, Treuting looks like a pontiff) in order to expose other color combinations. It takes a while to integrate our changing perceptions of this visual display with the intimate tangling that Marshall and Treuting do. She’s on his lap, curled around him so he can lift her shirt up to reveal another color, against which he places his hand, now in a bright yellow glove. Treuting’s spare, effective sound score and Eric Southern’s fastidious lighting augment every effect.

Jason Treuting’s hand against Susan Mashall’s back. Photo: Paula Court

The poses of the two performers or of all three with lifted arms may suggest diagonal beams of light, but when they arrange themselves on the table and stools, they could be a family (when Bocanegra sits, her feet don’t touch the floor, and she looks for a few seconds like a little girl). There’s drama too. Marshall lounges on the table, holding up a piece of paper. Treuting punches two holes in it with the point of a scissors; part of it is then pulled off. The process continues with him actually cutting the paper in two, while Marshall rearranges in her hand the increasingly small remaining pieces. Before long, what’s left is so tiny that you fear for her fingers. I think once more of a magic act (when he’s done, maybe he’ll open his hand and unfold the paper, and it’ll be whole again!).

In another sequence, while Treuting is crouched on the floor, Marshall repeatedly hits something on his back with a hammer. The sense that she is punishing him is twinned with a pristine, if starting effect: a sudden, loud musical clang and a change of color in the lighting.

In the end, the performers stand on edge in a row the three large panels that served as platters for the clothing. Then they leave the stage. The primary colors confront us: red, yellow, green. Wait! Changes in the lighting turn them purple, lavender, blue (can that be?), then brown, chartreuse, blue-green. They return to their first shades, then transform again. A low rumble starts up and a throbbing joins it. Red, orange, purple. Finally, the panels are back to. . .what should I call these?. . . their real (?) colors. Silence.

Will our eyes ever be the same?