Tiffany Mills premieres After the Feast at La MaMa Experimental Theater Club.

Mei Yamanaka supports Tiffany Mills in Mills’ After the Feast. At back: Kenneth Olguin. Photo: Theo Cote for La MaMa.

Tiffany Mills titled her latest work After the Feast, and the program note for its premiere during the annual La MaMa Moves! Festival asks the spectators to imagine: “an urban dystopia caused by vanishing resources.” In my mind, that includes considering the reckoning that may come as a result of our depredations on the environment. You do not attend this brave, socially-conscious dance expecting to be entertained. After the feast? Famine. And possibly worse.

Mei Yamanaka enters La MaMa’s Ellen Stewart Theater from behind the audience. She’s watchful, as if this is new terrain. Whatever it is, it’s unstable. The ground seems soft. She takes a step, hovers off-balance as long as she can and steps again.. A burst of static-enmeshed sound attacks her. Faster and faster, she staggers, until she can paste herself again the lavender-lit, beige-framed back wall designed by Dennis O’Leary-Gullo. Gradually the remaining members of Yamanaka’s tribe enter: Kyle Marshall, Jordan Morley, Kenneth Olguin, Emily Pope, and Mills herself.

Everything about After the Feast presages the end of a civilization: Jonathan Melville Pratt’s score with its moments of cataclysm, eeriness, fugitive melodies, pounding rhythms; Chris Hudac’s lighting design; and Mary Kokie McNaugher’s costumes.The six performers wear rag-tag outfits, some of which hint at mixtures from various cultures or eras—a hint of Roman armor, a Greek tunic. Torn, grubby, trailing, these pieced-together bits of clothing suggest that they’ve been worn for a long time. Pope has to manage one long mess of a sleeve that interferes with her left hand. It’s important that the audience sits on three sides of the space, and that often when the performers seem to exit, they simply walk behind one of the rows, corralling us here with them.

(L to R): Tiffany Mills, Emily Pope-Blackman, Kyle Marshall, Jordan Morley, Mei Yamanaka. Photo: Theo Cote for La MaMa

The program for this somber work lists nine short sections that bear names such as “Downpull,” “ReDevour,” and “Blood Moon.” I didn’t read them before I saw the work and can’t easily attach them to what I saw. But the message is clear, and it is saved from potential melodrama by its strong structure and the varied and nuanced performing that testifyies in part to the skill of the dramaturge, Kay Cummings (formerly my colleague at NYU-Tisch).

This group of six lives in an atmosphere of fruitless struggle. Whatever sustained them before is fragmented or not to be trusted. From time to time, a force pins them against the “wall,” where they move over and under one another as two-dimensionally as a Greek frieze, or remain motionless. They may have to be dragged back there. Only once do I see someone push against that surface. Olguin, the tallest man, behaves like a stern leader on the march, and the others fleetingly assemble to in a small horde behind him to copy his hard, fierce moves. In one of the strangest gestures, they hit their chests and forcefully swipe their hands from left to right. You can imagine they’re trying to move their hearts to a safer place. They focus intently downstage right, but seem unable to get there.

Kenneth Olguin tries to rouse Jordan Morley in

Tiffany Mills’ After the Feast. Photo: Theo Cote for La MaMa

They embrace, engage in brief combat, but most often they fall, and one of the most affecting passages is when all have collapsed but Olguin, and in the silence, he attempts to animate them. When he leaves, they begin to stir (the music roars at them). Mills looks as if she’s trying to re-learn the warlike moves. Pope is the last to rise, and you fear that she may not. Olguin returns, fiercer than ever (why did he leave, I wonder). The place they’re in is no more treacherous than their own inner devastation.

We see Pope alone, drawing something on the floor with her fingers, shaking frenziedly, being restrained by Yamanaka. Marshall enters, hooded; Morley struggles in on his knees like a penitant; Marshall picks him up and slings him to another spot on the floor. Seconds later Marshall is crawling laboriously on all fours, with Morley draped over his back. The six valiant performers pair up and dance, each of them with a hand over his/her partner’s mouth. At another moment, Marshall is standing, staring numbly into the distance, and nothing that Olguin (the only other person onstage) does can get him to move. Only later, does he go wild.

Emily Pope beleaguered in After the Feast. Photo: Theo Cote for La MaMa

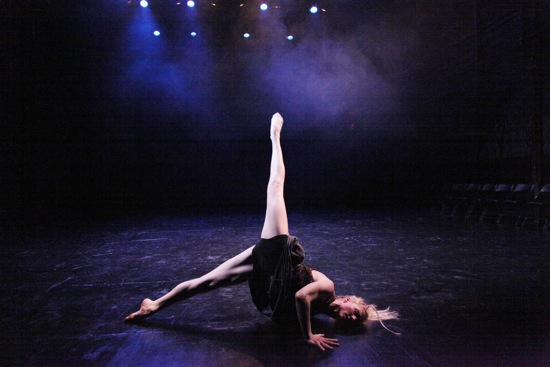

As these doomed people test the atmosphere, pause to think of their next move, learn from one another, fight, you accept their dancing as a way of life, their language. Every now and then, you see a “step”—maybe a leg raised high or a toe pointed that looks too “trained,” less urgent than it should. But when, for example, Yamanaka, braced on her two hands and one leg, waves the other leg in a circle as if she were desperately stirring the air, you don’t think about her technical prowess—only about her dilemma, even though you can’t know exactly what that is.

In the end, all collaborate in lifting Yamanaka high (she’s standing on someone’s shoulders) and walk steadily and carefully in that desirable down right direction). What lies out there? What do they hope for? I understand that at some performances, the lights go out as the group is reaching its chosen path; on other nights, Yamanaka loses her balance, and the final image is of her being caught. Either way, it’s hard to believe in a happy ending.