Rosane Chamecki and Andrea Lerner’s Eskasizer, at The Boiler February 26 through April 3.

An image from chameckilerner’s Eskasizer

Over the centuries, women’s bodies have been compared to many things. The amorous speaker in the Bible’s “Song of Songs” hymns his beloved’s breasts as being “like two young roes that are twins which feed among the lilies.” (He also likens her teeth to a flock of evenly shorn sheep). But how closely are those bodies seen by anyone but lovers and doctors? A woman needs a mirror—maybe two—to inspect her own back or look between her legs.

In their video/installation Eskasizer, The choreographers and video artists Rosane Chamecki and Andrea Lerner (partnered as chameckilerner) have created an onscreen vision of female flesh that makes you think of desert sands rippled by wind. The tension between the material and how it has been made to appear is almost shocking, yet curiously calming.

The bodies of four women dancers between neck and knee are projected on four large screens that occupy the walls of the dark, bare, high-ceilinged Brooklyn gallery called The Boiler. When I entered in darkness and sat on one of the red-brown leather beanbag chairs in the center of the space, I didn’t know beforehand that the women filmed were Gabri Christa, Hilary Clark, Jennifer Kjos, and Sally Rhodes, nor that they were at different stages of in their lives (one in her thirties, one in her forties, one in her fifties, and one in her sixties). Nor, in the gloom, did I notice standing near the entrance the Eskasizer that played a key role in the eponymous piece.

The Eskasizer, patented in the late 1950s, molded a generation or more of women, who used a passive method to tone themselves up and pare down their weight (their daughters and granddaughters would resort to more active exercise: running, taking aerobic classes. Plug the machine in, step onto its little platform, strap the wide belt around your butt or your belly or your thighs, lean slightly into it, and press the switch. That’s what those four performers did, and because they were dancers, they could also balance on one leg outside the belt and let the camera focus in close-up on their vibrating other leg.

I watched Eskasizer without all that information—not even knowing that Frank Stanley was the Director of Photography, and that Josephine Wiggs had written the spare, often meditative music that accompanied the almost 18-minute-long work. Neither was I trying to divine which woman was being featured when on which screen (no heads appear, nor arms or lower legs or feet).

The initial image clearly identifies itself as a human back between the base of the neck and the waist. It will eventually expand, filling the screen. But over the course of the piece, the images themselves do a kind of dance; perhaps two neighboring ones play simultaneously, then one may go black, and a third start up. At times, all four are filled with flesh. At times, they’re all dark. I thought I also saw a particular shot pass from one screen to another or duplicate it in perfect sync.

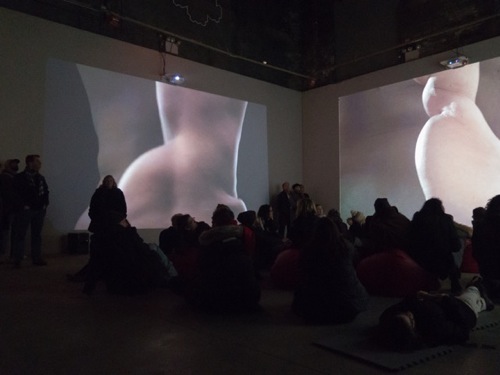

Opening night of chameckilerner’s Eskasizer at The Boiler

We rarely look at flesh magnified to that degree. Or flesh moving like that. As the camera travels closely over the bodies from neck to knee, they are being shaken by the Eskasizer’s vibrating belt. From my vantage point, as I lean back in my chair or squirm around in it, flesh becomes transformed. Waves of it form and re-form hills and valleys and narrow, shadowed crevices. I can also associate the motion with bread being kneaded without the help of hands; it seems—or is this my imagination?—to become more supple. Sometimes, blackness creeps in from one side and crowds the flesh, but more often the images fill their appointed space.

We know that the moving sculptural shapes are generated by passive women, a machine, and a camera, but nothing marks them as women (except, perhaps, the absence of major body hair in what the camera sees). No nipples appear, for instance, or obvious glimpses of the pubic area, although that occasional darkness amid the flesh suggests the presence of caves or round-edged, overhanging cliffs that cast shadows.

This is abstraction on a highly sensuous level. Our gaze roams over a landscape marked by pores, reddish spots, slight bruising, mottling, birthmarks, moles, tiny wrinkles. In at least one case, a slight fuzz of fine, almost white hair softens an outline. Some of the rippling forms are pink; others have a more golden tinge. Even if you’d read the program, you probably wouldn’t try to identify which body belonged to which female performer.

Chamecki and Lerner are always surprising me. Each of their pieces stirs up new questions. You want to ask them, how did you come to dream up Eskasizer? I forgot to put that query to Chamecki (she was gracious enough to give me a private showing, because I couldn’t make the scheduled ones). And I could have asked what the atmosphere was like when gallery had a lot of people in it. Did they roam around and talk to one another? Or were they silent during the presentation? Perhaps I was too mesmerized by chameckilerner’s amazing and beautiful installation to think of all that.

And since I am a woman and will never see the landscape of my own back, let alone trace the bones of my spine, Eskasizer struck me as both enlightening and profoundly mysterious. As well as beautiful.

Gorgeous writing, this is the flesh made word, so to speak, and I thank you for it.

Beautifully described, I share your observations, thank you Deborah. Andrea Lerner accompanied me through the mesmerizing experience on the last Saturday. a quiet meditation, thank you R&A.