John Scott and Valda Setterfield’s Lear. King Lear (Setterfield) besieged by a storm: Kevin Coquelard (L) and Marcus Bellamy. Photo: Maria Baranova

“Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks!” howls Shakespeare’s King Lear, defying the storm that crashes around him, as he wanders into outer reaches of his former kingdom. Thrust out by his two conniving daughters and their accomplices, accompanied by his faithful Fool and later by his youngest daughter, Cordelia (whom he had, in his erstwhile pride, gravely wronged), he is losing his wits.

But at New York Live Arts, in Lear by the Irish choreographer John Scott and Valda Setterfield, the king is Setterfield herself, a superb actor-dancer, and the storm is truly attacking her. Marcus Bellamy, Ryan O’Neill, and Kevin Coquelard (who at other times play the daughters) race around her, whipping long, crackling snakes of paper or tearing others into bits and pelting her with them as she huddles away from their onslaughts.

The two creators of this magnificent Lear share a common grief—the loss of parents through illness of body and/or mind. The mother or father who brought you up is now yours to plan for, yours to help, yours to comfort. Many grown children bear this burden gladly; others respond to the situation with annoyance and avoidance. Scott’s Lear makes no mention of many of the play’s characters, focusing on the prideful king and his children: the flattering, double-dealing Goneril (Bellamy) and Regan (O’Neill), and the honest Cordelia (Coquelard). Although a woman is playing a king, having the female roles played by men, as they would have been in Shakespeare’s day, gives the drama the boisterous energy of children and makes the tragedy all the more poignant.

(L to R): Marcus Bellamy, Ryan O’Neill, and Kevin Coquelard identify themselves as the daughters of Lear (Valda Setterfield). Photo: Maria Baranova

This Lear is also—via several “telephone calls” that Setterfield makes or receives— about a contemporary father and his adult offspring. We hear only the actor’s side of the conversations, which she delivers brilliantly; of course the scion in question may bring a friend to Thanksgiving dinner. He eats tofu, but not turkey? Oh. Fine. Of course. The person on the other end of the line is too busy to visit much. Nor does he/she like being called by his/her parents at 4 A.M. because a pipe has burst and they are truly terrified (Lear’s storm cleverly invoked?). Later in the performance, a standing microphone is placed before O’Neill, who announces grimly that the only possible future for his parent involves medication and being moved into a retirement home.

There is a third strand, and it is the four performers as themselves. Cordelia/Coquelard is too honest to overpraise her father the way Goneril/Bellamy has done (“I love you! I love you! I loooove you,” he shrieks, jumping up and down), and Regan/O’Neill’s colder beyond-exaggeration devotion. For a moment, Setterfield turns back into herself and urges, “Think about it, Kevin!” and (exasperatedly) “Kevin, have you read the play?” Yet after Coquelard, fumbling for words to express his feelings, erupts into furious French, he and Setterfield push their faces close together and snarl at each other— neither as themselves nor as Shakespeare’s father and daughter in dialogue, but channeling the aroused, animalistic ids of any parent and child who seriously misunderstand each other.

I cannot praise these three men too much. They invest every shift of character and style that Scott has devised with exactly the appropriate amount of power and nuances of intention. And Setterfield’s performance, is, as I have said, superb—deep and true on every level.

Lear is excellently supported by Tom Lane’s enriching and never over-bearing soundscape, and by James G. Everest’s introductory music. Eric Würtz designed the lighting and the black-and-white ambience, with signs hanging on the back wall that can be pulled down and displayed (“Ha!” say many of them). Lear’s throne is an ordinary armchair. Gabriel Berry’s costumes include a paper crown for the king—appropriate, given the fragility of his power. When the performers pull up the panels of white flooring and leave them piled any which way at the back, we can imagine Lear’s mind coming unanchored.

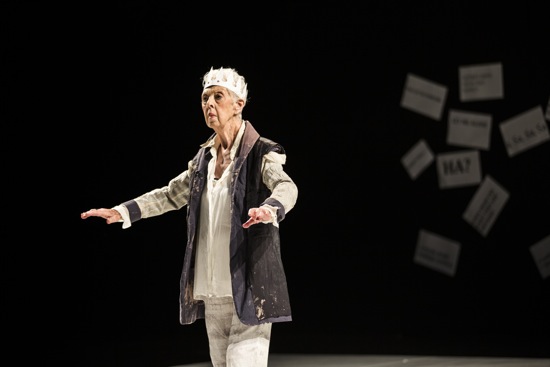

Valda Setterfield in Lear. Photo: Maria Baranova

In this atmosphere, Scott and the performers construct wonderfully revealing rhythms and movements. Setterfield begins alone, silently setting the scene with enigmatic gestures that will be repeated and transformed at various points in the action. We can imagine her acknowledging the homage of her subjects or presenting herself when she spreads her arms. Other gestures: she reaches out and, with a turn of her wrist, grasps air and brings it to her; she trembles her fingers to suggest rain falling or perhaps to flick things away. In all this, she is calm—both regal and ordinary—conveying with her shifting gaze and subtle dynamic changes the sense that she is remembering or foretelling events.

The three sisters dance brief, character-revealing solos that end with a bow to their father, but then advance on “him” in a close huddle—Bellamy and O’Neill pushing Coquelard ahead of them and all three jabbering noiselessly. Setterfield tosses out bonbons, which encourages the men to show off their jumps. But when she reaches out to them, they kiss the backs of their hands to her and turn to wiggle their butts in her direction. When she asks, “Are the horses ready?” they call out “Yee-haw!” and gallop away, as if to a cow-town saloon. They also reenter roistering— a triple image of Shakespeare’s jester, wearing hats and shaking tambourines. They’ve brought a hat and tambourine for her too, and she wonderfully shows us both the pleasure of being asked to join the “kids” and her fumbling bemusement in terms of how to go about it.

Lear (Valda Setterfield) rests, while ( to R) Kevin Coquelard, Ryan O’Neill, and Marcus Bellamy play the Fool. Photo: Maria Baranova.

It cannot be coincidence that in Lear’s remark to Goneril and Regan, “How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is/ To have a thankless child!,” the “tooth” has been changed to “tongue.” Bellamy and Ryan thrash Setterfield with words. One bit of Shakespearean text is passed from one of the three men to another a word at a time, jolting the sense out of it. Lear doesn’t at first recognize Cordelia (an especially poignant scene), and they crawl together on hands and knees like dogs needing to catch each other’s scent. But then Setterfield and Coquelard slide into other roles—a parent and a showing-off child. Watch me be a flamingo, he says, and struts for her. But when he starts careering around the space—leaping, skidding on the papers, falling, running again—she calls out “be careful!” like any worried mother or father, even though she’s entranced by his daring. Seated together on the floor, they sing, she occasionally lagging a little behind him. They read together from a piece of paper the hopeful speech that Lear delivers as the two are being hustled off to prison just before the tragedy reaches its end. Prison is not so bad, he tells her, “We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage.” And they’ll talk with other prisoners: “Who loses and who wins, who’s in, who’s out;/ And take upon ’s the mystery of things,/ As if we were God’s spies. . . .” Setterfield, as Setterfield, says that she likes that notion, and the two bundle up bunches of paper and play them as if they were tambourines.

At the end of the play, these four characters are all dead. In Lear, after more ado, the three daughters have fallen, a distant metallic, ringing sound announcing each death. But this king, who has been tenderly wrapped in paper by Cordelia, only appears to have died. Setterfield sits up with a gasp, as if too suddenly awakened, and calmly repeats those gestures of grasping something and pulling it down and making rain patter with her fingers or small things flutter away. The paper can now be torn up and the story ended.

Shakespeare ended his play with a brief speech by the Duke of Albany as he and two other lords gather the shreds of the kingdom together: “The weight of this sad time we must obey,/ Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say./ The oldest have borne most; we that are young/ Shall never see so much, nor live so long.”

With other kinds of eloquence, Scott, Setterfield, and their masterful colleagues reveal this truth and a great deal more.

Apparently, you and the New York Times’ Brian Seibert did not agree, save for the eloquence of the wonderful Valda Setterfield. One wonders (not having seen it myself) whether this is another case of NY Times manufactured venom for the sake of controversy. Or is it it simply a theater versus a dance critic? Regardless, it is great to see Ms. Setterfield carrying on with such panache.

How very interesting, both the review and this reconceiving of King Lear. I would particularly have liked to have seen the portrayal of Lear’s Fool, my favorite character in the play. Thank you Deborah, next best thing to seeing it myself, as I’ve said here many times, because it’s true.

in some productions, the Fool was doubled with Cordelia – they are never on stage together. In this Lear – the three daughters double as the Fool

I appreciate this amplification. When I mention in the first paragraph that Lear was accompanied by his Fool and later by Cordelia, I didn’t mean to imply that all three were together at the same time. Also, by using the term “jester,” I may have confused the issue of the three performers who played the daughters also playing the Fool in triplicate— i.e. “They also reenter roistering— a triple image of Shakespeare’s jester, wearing hats and shaking tambourines.” Perhaps John Scott also means to say that the daughters were pretending to be the Fool?

Interesting idea Deborah. My general idea, originally, was cheap double casting with an ambiguity of the daughters also being the fool and the actual performers: Marcus, Ryan,Kevin embodying the fool. there is something in the bluntness and clarity of the Fool that mirrors Cordelia – though the Fool gets away with it, while Cordelia suffers for being too truthful.