The Trisha Brown Dance Company presents three of Brown’s proscenium works in New York for the last time.

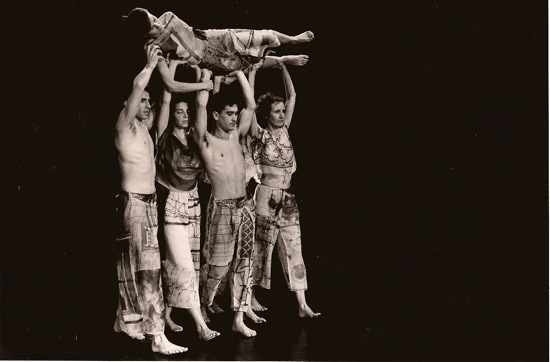

Trisha Brown’s Present Tense. (L): Stuart Shugg lifts Tara Lorenzen; (L to R): Marc Crousillat, Olsi Gkeci, and Jamie Scott hoist Leah Ives. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Goodbyes are never easy when you love someone. Or something. The Trisha Brown Dance Company’s season at the Brooklyn Academy of Music during the last few days of January represents the last time we New Yorkers will see some of Brown’s major works performed by her dancers. Just realizing that makes me wish I could embed them in my mind and engrave them onto my heart. The company’s three-year tour of “Proscenium Works, 1979-2011 is ending this February in Seattle, and artistic directors Carolyn Lucas and Diane Madden will focus on works grouped as “Trisha Brown: In Plain Site.” That means reviving Brown’s early task-related works and ones that were designed to be performed in black-box theaters or outdoor sites, plus perhaps reframing excerpts from proscenium pieces.

I never saw a Trisha Brown dance I didn’t love—the best of them thrilling. In the 1970s, I stood in the old NYU gym, to watch her Rummage Sale and Floor of the Forest—gazing at the dancers overhead, as they worked their way into garments threaded on a lattice of ropes on a wooden frame reachable only by a ladder; at the rummage sale underneath, you could buy, say, a lightly used sweater. In 1969, I lay on the floor of a gallery in the Whitney Museum, listening to Brown’s witty reminiscence/lecture, intermittently larded with the names of cities in order to help us construct a virtual map of the United States overhead. In a basement space on West Broadway, I crouched to watch her, Carmen Beuchat, and Sylvia Palacios Whitman climb stepladders, hitch themselves via ropes and pulleys to three of the inevitable pillars, and walk horizontally down them, spiraling as they went (Spiral was over when the dancers reached the floor, in maybe 20 seconds).

When Brown tired of what she dubbed Equipment Pieces, she embraced intriguing structures—such as those long sequences that accumulated gestures, one at a time (a memory job for the dancer, who had to go back to the beginning every time a new one was added). I remember when a man joined her small all-female company, and you could get slightly moist watching Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #75203 (1980). Stephen Petronio, Eva Karczag, Lisa Kraus, and Brown danced in the mist blown into the air by Fujiko Nakaya’s assembly of nozzles and the glow of Beverly Emmons’s lighting. That was in a down-at-heel, subterranean, brick-walled studio on Crosby Street.

The original cast of Set and Reset “walks” Diane Madden along a virtual wall. (L to R): Stephen Petronio, Vicky Shick, Randy Warshaw, and Trisha Brown. Photo: John Waite

It was also one of the first dances in the cycle that Brown grouped together as “Unstable Molecular Structures.” These works took her onto proscenium stages, commissioning scenery and costumes from notable artists, as well as scores that weren’t ambient noise or the sound of running water. The sensitively organized BAM programs began with Set and Reset (1983). Like molecules, it is full of slippery evasions and connections. Its structure keeps changing. Everything about it is on the move: Robert Rauschenberg’s collages of black-and-white films clips, the three structures on which they are projected, the side curtains that the dancers keep making billow as they enter and leave, their filmy costumes silk-screened with more Rauschenberg photos. In Laurie Anderson’s score, the composer’s voice (“longtime no see, long longtime no see”) emerges from the vibrant swirl of sounds.

The dancers’ legs fly effortlessly into the air; much is accomplished by the swing of a limb, a sprint, a spring. Their joints look well-oiled. As they swerve to avoid one another, or bounce off someone in their path, they still have time for cooperation. Leap, and your trajectory may be arrested in midair; topple, and you will be caught; collapse, and you will be carefully dragged offstage. A couple of dancers may travel the same path for a while, perfectly in synch. A stray individual may slip, as if by accident, into an ongoing pattern. Your spectating eyes are kept busy flipping around the stage, picking up an echoed gesture here, a divergence there, or a surprise (Olsi Gjeci, without apparent preparation, vaults over Leah Ives who has just happened to bend over. Stuart Shugg doesn’t arrive until close to the end, like a guest late to the party and eager to make up for lost time). The marvelous dancers are Cecily Campbell, Marc Crousillat, Tara Lorenzen, Jamie Scott, Shugg, Gjeci, and Ives. Crousillat is a slippery wonder in the final solo.

Jamie Scott (foreground) in a 2013 performance of Newark. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Newark/Niweorce (1987), which closes the BAM program, is the first dance in which Brown made a distinction between men’s bodies and those of women. Throughout much of this tough work, Crousillat and Gjeci plant themselves onstage, a certain distance apart, and keep forming blocky shapes, mostly in profile. At some point, they turn the whole design, facing the back of the stage as if it were their new front. Campbell, Scott, and Ives act more like free agents, silkier in their athleticism, coming and going, but occasionally fastening onto the men. Lorenzen seems a kind of hybrid, combining the “male” qualities with those of the women.

All the dancers wear identical gray unitards, and it takes Ken Tabachnik’s fine lighting to make them stand out against Donald Judd’s five vivid backdrops (two shades of red, yellow, deep blue, burnt sienna); these rise and fall at different times, changing the amount of space available to the dancers. Judd also collaborated with Peter Zummo on the spare sound score that sometimes unleashes a long, single, blaring note and sometimes falls silent.

Trisha Brown’s Present Tense. (L to R): Stuart Shugg, Tara Lorenzen, Leah Ives, and Marc Crousillat. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Sandwiched between these two masterworks at BAM is a less familiar, more recent piece of Brown’s: Present Tense. It premiered in Cannes, France, in 2003, and New Yorkers didn’t see it until 2005, when the Trisha Brown Dance Company celebrated its 35th anniversary season at Lincoln Center. In the latter years of her career, Brown occasionally set her dances to preexisting scores. John Cage’s wonderful Sonatas and Interludes accompanies Present Tense; the notes struck on a prepared piano sound as resonant as gouts of water hitting a gong. Silences fall.

The backdrop by the late artist Elizabeth Murray is a bold, hard-edged arrangement of angular and curved shapes in blue, red, and green, and Elizabeth Cannon has reimagined Murray’s original costumes in even brighter shades. Lorenzen begins Present Tense with a lively, beautifully performed solo, but before long the others arrive to get on with the principal job Brown set for them. It’s as if her early imaginative task dances have expanded into the building of witty and almost improbable sculptures and contraptions with human bodies. The performers are both jungle gyms and the kids playing on them.

Leah Ives travels along (L to R) Stuart Shugg, Marc Crousillat, Tara Lorenzen, and Olsi Gjeci. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

They dance as sleek and buoyant as seals in Jennifer Tipton’s splendid lighting, although they also occasionally sit and turn their heads sharply in a way that’s part-rabbit, part-windup toy. Ives and Campbell often work as a team. Six dancers on the run form two trios or three pairs. But bridges and tunnels are their main concern. The ways in which they link, buttress, climb, dive through, lift, and chain are fascinatingly complex or surprisingly tricky. Once Scott, on her way somewhere, runs along Ives and Campbell’s thighs as they stand bent-kneed. Another time, four of them make a “road” for a thigh-walk by Ives, with the back person running around to become the new front support.

I hope that the brilliant, ground-breaking artist Trisha Brown (now incapacitated and living in Texas) knows just how beautifully her dancers are carrying on. And that both her company and her work have a future. In addition to presenting her works in non-proscenium spaces, Madden, Lucas, and others can stage her dances for other companies, as long as enough time is allotted for them to get her distinctive style into their minds and bodies. (Good news: Stephen Petronio’s company will present Brown’s 1979 Glacial Decoy during its March season at the Joyce.) Sometimes, you have to say goodbye to some of the past in order to move forward.

Trisha Brown’s Present Tense. Leah Ives looks out between Olsi Gjeci (L) and Marc Crousillat. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Beautiful and valuable, a reverie review we can hold in our own hearts and minds, for which I for one am unspeakably and profoundly grateful.