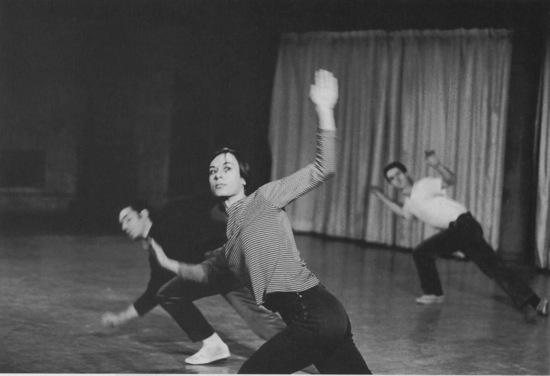

The 2016 Dance on Camera Festival.

The opening scene in Snags in Palladio by Michele Manzini

This year the Dance on Camera Festival celebrated its 44th anniversary and the 60th anniversary of Dance Films Association, which for the past 20 years has been partnering with the Film Society of Lincoln Center in presenting Dance on Camera. As usual, it was astonishing how many screenings, panels, master classes, workshops, and exhibits were fitted into venues at Lincoln Center and elsewhere between February 12th and 16th. By my count, 44 films—some long, some short—were screened. (For the record, I didn’t see the films mentioned below on the Walter Reade Theater’s big screen, but up close on my laptop.)

Dance documentaries built around a single person’s achievements willy-nilly follow a formula— a comfortable, often illuminating structure that’s shaped by the subject’s persona and the nature of his/her career. Loving to know more about people we admire, we see rarely tire of film clips of the dancer and/or choreographer captured during performance and with luck, in rehearsals. We examine childhood snapshots. He or she, shot in close-up or medium close-up, speaks to the camera and an invisible interviewer —the one making the film if the person is alive at the time. The subject may also be tracked walking along city streets or through backstage corridors or making coffee at home. Inevitably, relevant talking heads give their anecdotes and insights.

Merrill Ashley, the heroine of Ron Steinman’s The Dance Goodbye, in her prime at New York City Ballet

Ron Steinman built his The Dance Goodbye around the last moments of Merrill Ashley’s 30-year stint as a notable dancer in New York City Ballet before she retired in 1997, and he follows her transition into another career. The question posed onscreen is “What is life like for a dancer when a dancer can no longer dance?” Although Ashley ponders this for the camera, and her husband, Kibbe Fitzpatrick, mentions that she can sing (to which she retorts teasingly that she can sing about as well as he can play the piano), the answer, when it comes, is not unexpected. She currently coaches and stages Balanchine ballets for companies worldwide.

The handful of colleagues recruited to assess Ashley’s gifts are mostly male (e.g. Jacques D’Amboise, John Meehan), and they speak eloquently—although I would have liked to hear what another female dancer admired about her or learned from her. I could also wish that Steinman had shown more of that coaching that she evidently has a gift for. She herself talks frankly and modestly about her career transition and what she loved—craved—about dancing. Dancing made her feel fully alive; she likens the sensation to flying through the air as freely and naturally as a bird. But, as she says in the film, her life eventually focused too narrowly on taking care of her body and performing. We learn the details of her many injuries; we see her limping along before hip replacement improved her gait.

Merrill Ashley’s Farewell Performance at New York City Ballet

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The Last Goodbye gives us a wealth of film clips that show the gift for speed and precision that marked even Ashley’s childhood dancing. The high point is watching her in the 1978 Ballo della Regina (one of two ballets that Balanchine created with her in mind). She makes rapid, crazily tricky footwork look as natural as bird’s trilling, and the effect is electrifying. But Balanchine wanted to bring out other aspects in her dancing, and in a still photo of them standing together, she in what I took to be her costume for the Emeralds section of his Jewels (a dreamier role), he has his arm around her, perhaps demonstrating for her off-camera partner. She says in the film that in her dreams she still dances.

Yvonne Rainer, interviewed in Jack Walsh’s Feelings Are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer.

Jack Walsh took on a very different dancing subject for his Feelings Are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer. Hers is a complex career: a modern dancer becomes a vanguard choreographer, morphs into a independent filmmaker, and returns to choreography when she’s in her sixties. Rich territory to delve into for both the filmmaker and the film’s viewers. That Walsh compressed all Rainer’s accomplishments into 82 minutes is something of an accomplishment. I had to laugh, though, at one small irony. Rainer speaks of her early admiration of Martha Graham and her subsequent discomfort with Graham’s “inflated metaphors;” a few minutes earlier, this sentence appeared on the screen re her own 1966 solo, Trio A: “Dance would never be the same.”

Trio A was indeed a landmark in postmodern dance, and we see Rainer performing it in Babette Mangolte’s 1978 black-and-white film—a long trail of non-repeating moves executed with equal emphasis (or rather non-emphasis) by a dancer unable to avoid being charismatic. However, there were many other audacious works made by Rainer and her colleagues during the heyday of Judson Dance Theater, when the nature of dance itself was under scrutiny. The Feelings are Facts film also brings out her strategies for fragmenting and reconstructing narrative in the films that she began to make during the 1970s—at first as an element within a dance.

Rainer’s Trio A at Judson Church in 1966. Rainer with David Gordon (L) and Steve Paxton.

Feelings are Facts (titled after Rainer’s Feelings Are Facts: A Life (Writing Art) tells the story of her career in the two mediums through clips from her films, archival black-and-white footage, and contemporary revivals of her dances, plus new ones by the small group she calls “The Raindears.” We see Mikhail Baryshnikov working at being just one of the gang when he jump-started her return to dance in 1999 by inviting her to choreograph for his White Oak Dance Project. There’s no lack of smart, frank colleagues to speak about her work—Steve Paxton and Simone Forti from the Judson days, Emily Coates, Pat Catterson, art historian Douglas Crimp, actors Kathleen Chalfont and Joanna Merlin (both of whom were in her 1996 film Murder and Murder). Here was an artist who lived on the cutting edge, inventing new structures within which to dance, and occasionally startling even her colleagues. On the subject of Word Words, a short 1963 dance that she and Paxton each performed alone and then repeated side by side, both wearing only thongs, Paxton tells the camera, “I felt like my bones were blushing.”

In the 1960s, elitism was being questioned along with the distinctions between the arts, and one could find a New York apartment for under $20 a month. Rainer reminisces about the fertile atmosphere of the Cedar Tavern, where poets, musicians, and visual artists congregated in during that decade. And she speaks without rancor of her California childhood and parents who farmed her and her brother out to foster homes during a period when her mother couldn’t cope with caring for them. A brilliant thinker, occasionally wry about her own works and the rationale behind them, Rainer is her own best commentator. It is to Walsh’s credit that he gave us ample time to listen to her, as well as to glimpse her artistic accomplishments in both dance and film.

Enter the Faun by Tamar Rogoff and Daisy Wright (director and editor) is a different sort of documentary—one that takes the viewer along on an extraordinary journey by two unlikely colleagues, Rogoff and Gregg Mozgala—a journey that culminated in Rogoff’s 2009 dance theater work, Diagnosis of a Faun (a radical deconstruction of Vaslav Nijinsky’s 1912 ballet L’après-midi d’un faune) featuring Mozgala.

Rogoff, a venturesome, deep-thinking New York choreographer, is the daughter of a doctor and, as she says in the film, art and medicine mixed in the family household, where free calendars came in the mail with copies of great art on one side and instructions on how to inject an arthritic knee on the other. Mozgala, an actor, was born with cerebral palsy. Rogoff, who had already thought intensively about body intelligence, saw him in a production of Romeo and Juliet and somehow the faun as Nijinsky portrayed him invaded her mind. Enter the Faun details the process with which the two worked together, charting month two, month four, etc. and then counting down over the nine months that culminate in the performances at LaMama.

Gregg Mozgala and Emily Pope Blackman in Tamar Rogoff and Daisy Wright’s film Enter the Faun

Mozgala’s struggle with his body over those months is intense, and painful both physically and psychologically. He has developed a way of walking that’s almost a swagger; walking on tiptoe, his knees and feet turned in, he lurches along a sidewalk with big, fast steps. And he candidly, without mincing words, reveals his frustrations and his doubts to the camera and to Rogoff, who—calm and soft-voiced—asks the right questions and knows when to be silent. These two smart people easily goad each other into laughter.

Wright often has the camera move close to the subjects, picking up on the intimacy with which choreography and therapy progress. We see mainly the upper bodies of Mozgala and Emily Pope-Blackman (who appears in the performance as “Dr. B.”), as the two work to accommodate to each other’s moves in an ongoing flow of call and response (this is very hard for Mozgala, who has issues about touching and being touched “I have no fucking idea what I’m doing,” he says in a voiceover). Once, when Rogoff is crouching on the floor, her hands on Mozgala’s ankles and feet, the camera shoots the process in extreme close-up, with her head framed by his calves. In one process aimed at helping Mozgala to release some of the constant tension he maintains throughout his body, the two slowly roll together over the floor; Rogoff’s voice and the pressure of her hands and body insists here, suggests there, as she senses where he is holding, when he is letting go. The camera, moving in close, wants us to look for—maybe to see—changes.

And we see a lot. When Mozgala stands in profile, and Rogoff asks him quietly to “soften the ribs in front,” the small, but vital adjustment in his posture that this induces seems momentous. There’s a truly earth-shaking moment during the fourth month: Mozgala’s heels touch the floor for the first time in his life (!). Those feet that he has thought of as “dead appendages” can slowly walk along the floor and feel its surface (“My feet,” he says, “are going to take over the world.”)

In this film, some of the voices belong to the other performers who appeared in Diagnosis of a Faun: Pope-Blackman, Lucie Baker, and Dr. Donald Kollisch (who plays an orthopedic surgeon). But another speaker is an impressed neuroscientist, and still another is a gold-medalist in paralympics, who was deeply moved by what he saw in an open rehearsal. Enter the Faun takes viewers into the first rehearsals at LaMama and shows some clips of Diagnosis of a Faun in performance during its 2009 season there. Back then, I found it an amazing work of art (Here’s a glimpse of both the film and the performance): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NVEx715FfcU).

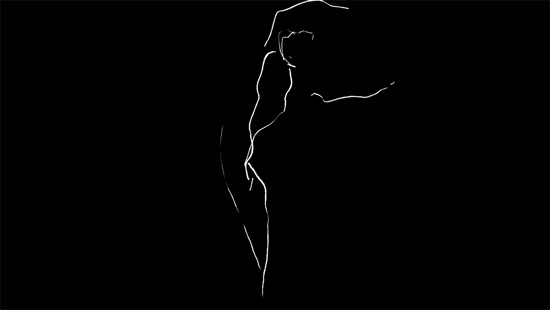

Study #1, a film by Gregory Bennett and Jennifer Nikolai.

Among the films on view during Dance on Camera are twenty-four short experimental ones (all under ten minutes, and many less than half that long) that explore the many possible relationships between film and dance. In this year’s two programs, you can experience not only filmmakers working with traditional techniques, such as cut, fade, and dissolve, but ones who are also probing more recent technology— motion capture, for one. Some of these film artists are out to create beauty; others are intrigued by film’s natural ability to suggest mystery (What are we not seeing? Is this a dream? Is that red spot his blood. . .or hers?). At times, visual trickery becomes the main subject.

Danny Gardner (L) and Geoffrey Goldberg in Gardner’s A Tap Dance in a Circle

Danny Gardner’s charming 3-minute A Tap Dance in a Circle is at the low-tech end of this year’s lineup. The camera follows in a single take a man in a park (Geoffrey Goldberg) and a “Tap Stalker” (Gardner) who lures him into his routine. The high-tech end might be New Zealander Gregory Bennett’s 4-minute Study #1, in which dancer Jennifer Nikolai, via motion capture, becomes a storm of curving white lines on a black background, only fleetingly identifiable as a moving human being as she seemingly attacks and melds with herself.

Somewhere in between these extremes, one might fit The Song of GuQin—Chinese Ink by Alex Wu (Zhen Wu) of China. Via Chroma-keying, The cinematographer has inserted one or two figures performing movements drawn from classical Chinese dance into ink-wash drawings that allude to the ancient landscapes we know through art. In these landscapes, smoke can billow, cranes can fly, fish can leap from a blue sea. And embedded in them, tiny figures at first, a man and a woman dance separately; eventually they meet, now definitely human and in love. In one entrancing poetic sequence, the camera scrolls down from the clouds and birds, past a tiny house, and discovers the two of them together on a bridge.

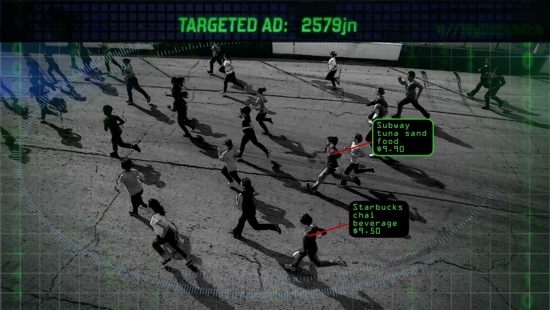

Mitchell Rose’s Targeted Advertising

In film, it’s easy to make dancers part of a larger design—one that might not fit on a stage or be seen to advantage on it. Mitchell Rose’s Targeted Advertising (4 minutes) makes witty use of a horde of dancers drawn from two participating dance departments and set into patterns by Susan Hadley, who, like Rose, teaches at Ohio State. We see them as small figures running, while labels attach themselves periodically to them. Targetted advertising in its most absurdly literal form. A man flees. Is it “Viagra” that’s pursuing him?

Jody Oberfelder’s Dance of the Neurons at warp speed.

Interested in brain-body connections, choreographer Jody Oberfelder, with Eric Siegel, created the clever Dance of the Neurons with twenty-four dancers standing in for those infinitesimal units. Wearing colored t-shirts, they seem to clamber up a wall and disappear out the top of the screen, but their gradually speeding-up chains are actually achieved through an overhead shot of them crawling on the floor. A shot of linked groups of four struggling dissolves into one of a big clump holding hands and swaying. This depiction of the birth of neurons is assisted by symphonic music that both heralds it as a cosmic process and hints at irony.

Galen Bremer’s know you: Emma Hoette and Zoe Rabinowitz

Enigma abounds even in the intimately scaled know you by Galen Bremer. We certainly don’t get to know the two women (Emma Hoette and Zoe Rabinowitz) wearing beige overcoats, who walk around and along an enigmatic outdoor sculpture somewhat like a bridge and a doorway. To a sustained tone with underlying beats, the women pace. Usually we see them from the rear or focus on their identically shod feet. They dance a bit. One falls back and disappears. . .caught by the invisible other? Are they friends, or is one a doppelganger?

Homei Toyoka in Sebastian Gimmel’s Approaching the Puddle

In Approaching the Puddle, by Germany’s Sebastian Gimmel (9 minutes), the everyday and the mysterious mix eccentrically and, in some way rhythmically. A young woman (Homai Toyoda), dressed for rain in a hooded coat and yellow boots, stands in a deserted area in an alley or parking area among city buildings. She’s attracted to a tiny puddle in a hollow spot of gravel. She scrapes a foot along the gravel, making a sound; she turns her feet in and out. Gimmel mixes longish shots with closeups, as Toyoda jumps over one puddle and finds another. That’s when we see that there are many such puddles here. One of the camera’s tricks is to let the subject move out of the frame, then find her elsewhere. Numerous cuts add to the eeriness of the work, as Toyoda tries out big, rough-edged dance moves with the impulsiveness of a child playing alone. Then (surprise!), she is dragged away by invisible hands and reappears prone several feet off the ground above the little water hole, spinning. You can’t, I guess, trust a puddle.

Belle Sodhachivy Chumwan in Chris Rogy’s SajakThor

Sometimes there’s more fantasy than you can grasp or follow, but you can admire such ravishing images as one of a woman in a slim red gown ascending the steps leading to a Palladian villa; the yards-long skirt that trails yards behind her as the camera watches her from behind can make you think of blood (Michele Manzini of Italy’s 6-minute drama of thresholds and women half-seen: Snags in Palladio). You can be entranced by a beautiful Cambodian dancer, Belle Sodhachivy Chumwan, in SajakThor dreamily embodying with her supple fingers and fluid gestures an apsara, one of Hinduism’s dancing deities, even though her ritual for peace is sometimes viewed at awkward angles and with often jarring cuts by filmmaker Chris Rogy.

A number of the films tell stories—fantastic or nightmarish ones—with varying degrees of success. And a bit of mystery motivates many supposedly straightforward ones. A smiling couple (Carlos Gonzalez and Tina Vazquez) check into a tropical inn in Marta Renzi’s Honeymoon (6 minutes), bearing a copy of the Kama Sutra with them. Although they consult it, this film is no sex manual illustrated. The camera scans the two reticently as items of clothing fall to the floor, and, although their bodies slip together in erotic ways, Honeymoon alludes to sex through dancing—intimate, complicated, pleasurable, and unselfconscious. A shower is turned on. Cut to the pair dressed as they look out the window. Laughing, they open the door and go out into. . .snow! Is this a gentle hint at climate change, or just a sweet joke? In any case, only film can give you a jolt like this.

A still from Marta Renzi’s Honeymoon