A company from London and one from Seattle visit NYC.

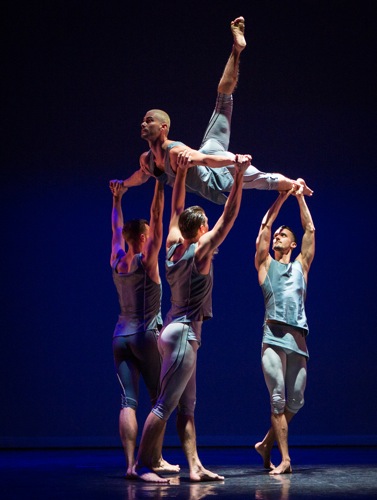

Andrea Carruccio of BalletBoyz® aloft in Christopher Wheeldon’s Mesmerics. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

History often appears less as a straight line than a looping, occasionally tangling collection of threads. Before Michael Nunn and William Trevitt founded Ballet Boyz in 2000, they were principal dancers with Britain’s Royal Ballet. That’s also the year that Christopher Wheeldon, formerly in that company, stopped dancing in the New York City Ballet to pursue choreography. Eight years ago, Wheeldon founded his own company, Morphoses, and Ballet Boyz appeared at Jacob’s Pillow as a trio (Trevitt, Nunn, and Oxana Panchenko). Now the correct name is BalletBoyz®, and during its season at New York’s Joyce Theater, its ten men perform Wheeldon’s revised Mesmerics, which in 2003, was a dance commissioned by the Joyce for the three men and two women when Ballet Boyz called itself George Piper Dances.

The image that BalletBoyz® presents is less about ballet in its most classical sense than about boyz. And, whether you spell that with a z or an s, the guys in question are men and extremely strong, nimble, personable ones. This impression is knocked home by the projected information about the company—film clips of rehearsals and other related events, remarks by dancers, etc. —that prefaces each dance.

Alexander Whitley’s The Murmuring: (L to R) Jordan Robson, Flavien Esmieu, Harry Price, Matthew Sandiford, Matthew Rees, Marc Galvez, Edward Pearce, Andrea Carrucciu. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The Joyce program opens with Alexander Whitley’s The Murmuring, set to the so-titled ominous electronic sounds of music by the London-based duo Raime, and lighting designer Jackie Shemesh first reveals the scene in a beam of light, with smoke seeping onto the stage.

Whitley has said that he was influenced by murmurations of starlings—their flocking and wheeling, settling and squabbling. And the most vivid recurring image in the dance is one in which the men cluster and—hanging onto one another—reform that nucleus in various ways. In one instance, Matthew Sandiford anchors its core; around him, the others smoothly duck under and climb over their colleagues’ clasped hands.

Whitley pursues his theme of joining and separating throughout The Murmuring. Near the beginning, it’s Edward Pearce who pulls away from the group. Two men pick up his big, smooth, energetic moves before he rejoins the others. Like gang members, the guys are always alert to what’s going on. When not dancing, they’re watching those who are. And, like starlings, they’re scrappy and bold, whether they’re wheeling in a loose formation or showing their winging style. Sometimes they wrench their bodies into motion; sometimes they reel away from an unseen gale. They often fall, roll, and launch themselves into motion again. They spin, lift one another, wrestle. Marc Galvez battles the air in a solo.

Marc Galvez in Alexander Whitley’s The Murmuring. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

If the dance feels long, spinning its wheels toward the end, it’s not the fault of the performers (the other fine ones are Andrea Carrucciu, Simone Donati, Flavien Esmieu, Bradley Waller, Harry Price, Matthew Rees, and Jordan Robson).

After intermission, the onstage projection says, “Welcome back” and shows us Wheeldon rehearsing the men in Mesmerics. We’re told that this ballet has no story. But the choreography, set to five pieces by Philip Glass, tells its own story—one of structure, spatial design, and rhythm, which Wheeldon handles with almost intoxicating deftness. And lighting designer Natasha Chivers is complicit in this. In the beginning, Sandiford moves alone in a pool of blue light. Behind him, in another, more dimly lit pool, another man copies him. Although Sandiford acquires a partner, the other does not, yet he nevertheless embraces and manipulates air in synchrony with Sandiford, until he is replaced by a pair in another pool. Eventually there are three couples, each anchored in its own space and the choreography has progressed from focusing on the men’s twisting, curving torsos and arm gestures; now their legs have freedom to lift and kick out. Glass’s “Mishima,” “Company,” “String Quartet #5” (an excerpt?), and “The Secret Agent”—all dissimilar and all separated by silences—key subtle changes in the dance.

Matthew Sandiford (foreground) and Flavien Esmieu in Christopher Wheeldon’s Mesmerics. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The ways in which Wheeldon empties and fills the stage never seem unhurried. The men, wearing tights and smartly cut vests by Amanda Barrow, fit into and out of patterns—now four of them run in a circle; now four appear in a corner, acquire a fifth, and travel sideways; now they leap; now three or more collaborate to “fly” another man. The solo cello refrain in Glass’s “The Secret Agent,” sounds almost Bachian. In this last section, Sandiford rolls onto the stage, whipping one arm around, and the stage’s back curtains part to reveal three silhouetted figures. Dancers begin running in and out, assembling and disassembling: Carruccio suddenly alone, then to trios forming, then four men meshing their arms and bodies as if they were cranks and levers. Then Carruccio alone again in the light and the space, balancing in one leg, the other lifted in an arabesque like a beacon.

George Balanchine, a sublime classicist, didn’t spend much time thinking what defined a ballet. He understood the classical tradition so well that he could twist it, invert it, and send it flying at astonishing speeds. The all-Balanchine program presented at City Center by the Seattle-based Pacific Northwest Ballet, directed by onetime New York City Ballet principal dancer Peter Boal, vividly shows what those who frequent the NYCB know: the music that inspired Balanchine whispered to him of chandeliers and elegantly prepared-for pirouettes or knotty liaisons and briefly turned-in feet—all to be passed through his contemporary sensibility.

Pacific Northwest Ballet soloists Leta Biasucci and Benjamin Griffiths in George Balanchine’s Square Dance. Photo © Lindsay Thomas

PNB performed in a theater where many of us first saw NYCB. City Center’s big, but not huge theater and moderate-sized stage promotes a kind of intimacy. The orchestra pit doesn’t keep the first row of audience at much of a distance. So it’s exhilarating to see at fairly close range the vigor, finesse, and high spirits with which this west-coast company performs three Balanchine ballets: Square Dance (1957), Prodigal Son (1929), and Stravinsky Violin Concerto (1972

At its premiere by NYCB on this very stage, Square Dance charmed audiences by an unexpected cross-cultural novelty. The dancers stepped out to music by Antonio Vivaldi and Arcangelo Corelli, both born in the latter half of the 17th century. But their patterns were (supposedly) being summoned up by a square dance caller at the back of the stage. Some may remember his ingenuity in, say, rhyming “quick” with “here comes Nick” (principal dancer Nicholas Magallanes). In 1976, Balanchine redesigned the ballet, doing away with the caller and relegating the onstage musicians to the pit.

George Balanchine’s Square Dance. (L to R): Cecilia Iliesu, Ezra Thomson, Price Suddarth, Angelica Generosa, Leah Merchant, and

Matthew Renko. Photo: © Lindsay Thomas

Wearing white or pale practice clothes, the PNB dancers fairly tear into Square Dance, as staged by Boal. Balanchine’s choreography is ebullient—full of aerial steps like entrechats and gargouillades, and the six men and six women execute them pristinely as well as vigorously and with high good humor. The string players conducted by Allan Dameron seem hardly busier than the dancers’ criss-crossing, beating-together feet, and the sweet music never stops promoting harmony in daring. The dancers are not saying—as they often seem to in canonical ballets—“watch what I’m about to do;” they say “I’m having a wonderful time tonight,” as if the difficult steps were just part of a lively conversation.

The choreography also alludes to the fact that not only does square dancing involve couples, but that during a square dance, the women and men frequently receive separate commands (e.g. “Ladies to the center and back to the bar. Gents to the center and form a star”). Which means that half the dancers may have brief waiting times, while the other half watches. In many of the ensemble passages, Balanchine plumbs this structural idea in his own way, and the resultant image is of a high-spirited but polite group of six couples in which the men stay still to appreciate their partners’ forays and vice versa.

One of those couples heads the dance party, and Leta Biasucci danced charmingly on opening night. Her partner, Benjamin Griffiths, supported her admirably, but seemed a little restrained (perhaps opening-night tension), his gaze not fully engaged with hers. He came into his own, however, in a final solo that bespeaks loneliness and a touch of regret.

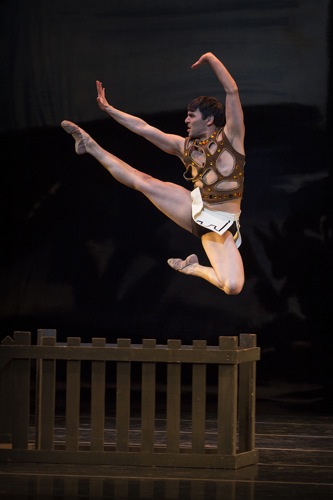

Jonathan Porretta in George Balanchine’s Prodigal Son, choreography by George Balanchine Photo © Lindsay Thomas

Boal, who was himself brilliant in Prodigal Son, staged this revival too. And his direction brings out the rough energy of the modernist ballet. Ballet? Hardly a step of it appears in the classical lexicon, and the pas de deux between the runaway youth and the predatory Siren subverts the usual supportive maneuvers in order to emphasize her cruelty and his awkwardness (she sits on his head for heaven’s sake).

The young Balanchine produced this biblical tale for Les Ballets Russes in the spring of 1929, three months before its founder-director Serge Diaghilev died. Like all Diaghilev ballets, it involved a librettist (Boris Kochno), a collaborating composer (Sergei Prokofiev), and designs by a noted painter (Georges Rouault). So I’m not certain who came up with some of the ideas—such as the single wooden structure that serves as banquet table, fence, pillar, slippery slope, and boat. Another brilliant strategy was to distill all the temptations and problems that the adventurous son encountered in the biblical tale into the machinations of single, powerful vamp of a woman and the squad she commands. Boal’s direction cleverly emphasizes not just the freaky nature of these nine guys, with their bald pates and identical tunics, but their bizarre unison moves. They jump bigger and harder than the men in other casts that I’ve seen and land with their knees more bent and their feet wider apart, which somehow makes them look both lustier and more morally deformed.

Pacific Northwest Ballet’s l Lesley Rausch as The Siren triumphs over Jonathan Porretta as The Prodigal Son in Balanchine’s 1929 work. Photo © Lindsay Thomas.

At the opening-night performance, The Son was sensitively portrayed by Jonathan Porretta, who brought more than his strength and splendid high jumps to the role. Sturdy and round-faced, he made the character seem younger and more vulnerable than, for example, Edward Villella, who memorably danced it like an angry, daring teenager. Lesley Rausch was scheduled to play the Siren on the second night, but had to take over from Laura Tisserand on the first. She appeared at that performance to have some difficulty with the long red cape that must be pulled between her legs and wrapped around one arm before she can strut, and she seemed more to be staring angrily at the audience than gazing coolly into the distance as she embraced Porretta the way a spider might constrict its prey.

Boal’s direction brings out the best in a cast that includes Chelsea Adomaitis and Cecilia Iliesiu as the Prodigal son’s mild-mannered sisters, Otto Neubert as his father, and Kyle Davis and Ezra Thomson as the friends who are so easily drawn into the Siren’s gang of “Drinking Companions.” I must, however, rail against the new costume for Porretta; the leather harness has become a gold-sequined one. Rouault and his colleagues must be pirouetting in their graves.

In Stravinsky Violin Concerto, the dancers again wear practice clothes, but in this ballet, which premiered during the remarkable NYCB Stravinsky Festival honoring the composer (and Balanchine’s friend) who had died in 1971. His 1931 Concerto in D for Violin and Orchestra, with its zesty parts and its beautiful, singing dissonances spoke to Balanchine of angularity. Emil de Cou conducted the excellent Pacific Northwest Ballet Orchestra for this as well as for Prodigal Son (Allen Dameron led the musicians for Square Dance).

Jerome Tisserand and Lesley Rausch of Pacific Northwest Ballet in George Balanchine’s Stravinsky Violin Concerto. Photo: © Lindsay Thomas.

It has always fascinated me that Balanchine chose to bring out contrasts and similarities in the groups that succeed each other onstage during the first movement—flashing their legs around, turning their knees in and out, flexing their ankles, and swinging their hips in response to the jazzy undertones of the score. The first horizontal lineup consists of a woman (Rausch) with four men flanking her. Then Noelani Pantastco appears in the same formation with four other men. Four women escort Jerome Tisserand , and more more bring on Seth Orza. Then each accomplished leading performer appears alone with dancers of his/her own gender. For each presentation in this series of introductions, Balanchine comes up with variants of the frisky steps, playing games with what we see. Is the soloist a jewel in a setting, or a person with his/her friends. How much does gender matter?

It matters, of course, in the two ensuing duets—both wonderfully ingenious, both stretching the concept of an intimate encounter between a man and a woman in pointe shoes into something strange —sometimes tender, but also investigative and challenging. In this staging by Paul Boos and Colleen Neary, Rausch and Tisserand, Pantastico and Orza excellently bring out the relationships that Balanchine articulated. Tisserand is more the attentive male, helping Rausch to look strong and beautiful in ways both traditional and unusual. There’s more struggle between Pantastico and Orza, but no antipathy; it’s simply a matter of how two dissimilar bodies/people find common ground.

I regret that I was unable to see PNB’s other City Center program consisting of recent and new works by David Dawson, William Forsythe, and Crystal Pite. It’s a company worth knowing well and seeing often.

I recently saw PNB dance Jean-Christophe Maillot’s Romeo et Juliette in Seattle, and while I’m not entirely keen on his highly intellectualized take on the ill-starred couple, I thought of what you said in a review of a much earlier performance by PNB at City Center, in the late Nineties, “I had forgotten what it is to fall in love with a ballet company.” We are extremely lucky to have them in the region for which they are named and I’m hoping to get up to Seattle more often. But sequins, on the costume of the Prodigal Son? What ARE they thinking. Thanks for vivid writing about both performances, comme toujours.