The Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company performs at the Joyce Theater through February 14.

Members of the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company, plus guest artists Alwin Nikolais’ Crucible. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The man sitting behind me at the Joyce Theater was enthralled by the Alwin Nikolais Celebration. He mentioned a possible connection to Blue Man Group, and dancegoers over the years have seen Nikolais’ influence on Pilobolus, Momix, and the Swiss Group Mummenschanz. But Nikolais (who died in 1993) was a unique master magician with color, light, sound, props, figure-altering costumes, choreography, and those dancers who were both part of his palette and the individuals who brought the landscape to life.

At the Joyce, the performers are members of the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company of Salt Lake City, the group chosen in 2002 to preserve and perform Nikolais’ works. That choice was made by choreographer-dancer Murray Louis, director of the Nikolais/Louis Foundation. And many of those in the audience Tuesday night were mourning Louis’ death on February 1 at the age of 89. He should have been there to see the Utah dancers do his onetime partner and mentor proud in dances coached by the now sole artistic director of Nik’s works, Alberto del Saz. His spirit certainly lives on in the choreography that he had been part of, beginning in the early 1950s.

It has always seemed pertinent to me to remember that Nikolais began his artistic career as a puppeteer. And that’s not just because he used to sit in the glass booth above the audience at the former Henry Street Playhouse, playing the musique concrète that he composed on a tape recorder and summoning up the play of lights and slide projections on his choreography—the controlling mastermind. But Louis was his muse and partner, and the uncanny physical dexterity that he possessed had an impact on the company’s style. In addition to possessing the necessary skills for a modern dancer (leaps, falls, turns, etc.), he could fine-tune his body to create a small ripple here, a twitch there, a flip of the hand, a small dance of the knees. He created his own fluent rhythmic narrative. And sometimes you could see the puppet quality in him—not just in his jaunty, sometimes impish, persona, but in the way one leg could fly up with no apparent effort, the looseness in his hip joints, the way the lift of an elbow could instigate the follow-up of a wrist.

“When he is around,” Nikolais wrote (in a 1971 issue of Dance Perspectives), “Death hides. . . .He shakes passivity—he shames stasis—he berates contentment. When he leaves—there still trembles a rattled vacuum.”

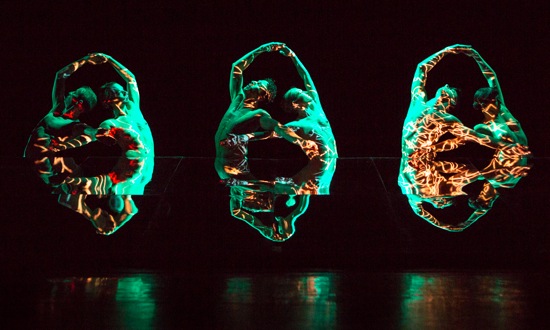

The Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company in Alwin Nikolais’ Crucible. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Nikolais abhorred hearing people call his work “dehumanized.” His philosophy, he wrote, simply involved “man being a fellow traveler within the total universal mechanism rather than the god from which all things flowed.” And one of the pleasures of seeing his dances again at the Joyce comes from the fact that it is ultimately human agency (i.e. the dancers) that creates the illusions; no computer-generated trickery is involved. For instance, in Crucible (1985), it doesn’t take a spectator long to realize that the nearly stage-width, slanted mirror “wall” behind which the dancers (wearing only flesh-colored jockstraps) work are what has concealed their legs and duplicated their upper bodies and arms where their legs ought to be.

At first, in rosy light, we see only their arms, with their hands playing at being predatory mouths. Small hands nest in bigger ones and are occasionally swallowed. In another section, we see only their doubled legs kicking. In another, their buttocks first arise like hippos surfacing from a pond. Sometimes, bending and arching, they can make you think of seahorses maneuvering through a pond. Ultimate, they become a group, with faces and urges.

The music for this, as for all the other works, provides various kinds of rhythmic, burbling beats with other sounds winding in and out or popping up as punctuation or cues to movements (I confess to not being a fan of Nik’s music, but its frequent air of a carousel calliope running amok suits the playfulness and wit of some of his images).

Three disguised dancers in Alwin Nikolais’ Gallery. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The 1978 Gallery, which ends the program, is one of a number of Nikolais works that end in disaster (storms of fabric collapsing onto the dancers, structures crumbling, strings being cut). In this case, the title refers to a shooting gallery in a fairground. The dancers are again concealed behind a wall. Duck down, and they disappear, only to pop up again as a row of green-lit heads with glowing red eyes (black unitards and hoods make the rest of them invisible). When one or more of them is shot (“bang!” goes the music), the picture changes, but they keep flipping back into view; sometimes, they’re not human heads but green disks with red centers or black-and-white pinwheels that the dancers hold up. Given the audience-performers orientation, we have been turned into the shooters aiming for a prize.

Clowns in Alwin Nikolais’ Gallery: Bashaun Mitchell and Juan Carlos Claudio. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

There are jokey moments. Juan Carlos Claudio and Bashaun Williams—masked as clowns, their bodies concealed within silky rectangles (black in back to make them look insubstantial)—nudge each other into floating side to side; one dancer, the last standing in a sequence, thumbs his nose in either direction; several of the others mime killing one another. However, there’s something sinister about our role in relation to the unseen mechanism that’s operating this “machine.” At times, the masked dancers stare toward us almost tauntingly. In the end (by the skillful use of pieces of black tape), both the disks and the masks appear to have pieces shot out of them, and those severely damaged heads are the last thing we see.

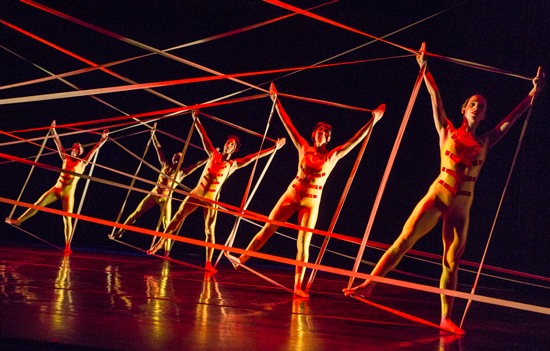

The earliest work on the program is Tensile Involvement (1955), a marvel under five minutes in length. In it, the dancers are fully visible as nimble manipulators, each of the eight controlling two elastic strands that are anchored high in the various wings of the stage. As they race on and off, lean, bend, kneel, stretch up, or change their grip, they create a gigantic, constantly reforming cat’s cradle. Using both hands and both feet, they build frames around themselves with the lower parts of the strands and tilt from side to side. Whoosh! The lighting turns blue, as they lie on their backs and reduce the size of the frames. On occasion, a couple of soloists leap into the mix (Yebel Gallegos and Bradley Beakes); once Gallegos grabs all the ribbons so that they briefly fan out around his waist. You can only imagine what the dancers have to do in their moments offstage to keep the geometrical design alive.

Alwin Nikolais’ Tensile Involvement: L to R) Aaron Wood, Bashaun Williams, Juan Carlos Claudio, Lehua Estrada, and Mary Lynn Graves. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Mechanical Organ (1980), the most recent dance on the program, is, like many Nikolais works, in suite form. Six sequences show aspects of the idea. The dancers are not disguised. They wear the unitards designed by Nikolais and Frank Garcia, and, at first paired up on three benches as male-female couples, they mime dependency and physical chit-chat. In another section, Beakes and Bashaun Williams take turns using each other as implements in balancing acts that can make a spectator’s abs ache in sympathy. Melissa Rochelle Younker delivers some fascinating moves that are both flexible and awry in “Doll with a Broken Head,” and Gallegos and Mary Lynn Graves dance at gleeful cross-purposes and inevitable agreement in “Two Not Yet Together.”

Nikolais’ dream worlds are both as dazzling and jangly as a carnival and precisely designed with a masterly hand. He must have wanted to delight us, that’s clear. But he also reminds us—often satirically— that ideals may topple and bright colors fade. Coming down from a high? Watch that you don’t belly-flop.

Alwin Nikolais’ Tensile Involvement: (L to R) Katherine W. Hunter, Melissa Rochelle Younker, ?, Alexandra Jane Bradshaw, and Bashaun Williams. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

You honor the choreographer, the dancers and the readers with this post, Deborah. Lovely, funny, eloquent, vivid writing, many thanks.

Thanks for doing justice to the memory of this great artist.

A dance concert can’t show the other important aspect of Nikolais: the fact that he was arguably the greatest theorist and pedagogue of dance, certainly the greatest theorist who also left a large body of wonderful work.

Deborah; Thank you for this writing on Ririe-Woodbury’s performance. Exhilarating to read you and see/feel

the resonance and weave of early choreographers through the present day dancers, and audience members. So good in so many directions. Bravo to all.

I enjoyed, very much, your review of Nikolais revivals. It reminded me of when, in the mid 1970s, I was teaching in New York for Robert Joffrey and several of the Nikolais Co. Dancers came to my classes. They were very good, hard working and obviously inspired dancers. I always tried to see my professional students in performance in order to know what was, at the time, most needed and pertinent for them in class. When I saw the company perform, the spectacle as a whole was intriguing, often ingenious, but I couldn’t see what the dancers were doing, from the point of view of a teacher, as so much (certainly leg and footwork) was hidden because of costumes, lighting etc. So I asked a couple of the dancers to show me what was going on that I couldn’t see. I was amazed when they showed me so much that had been totally obscured. Some really good, interesting things to see or do. I wondered, but didn’t ask, if the dancers were aware of it.

.

Dear Deborah,

Thank you for your long and detailed review of the Nikolais concert. Your writing has lasted at least as long as our company (52 years). You have been an astounding voice for sometimes esoteric modern dance. Your insights and explanations help to educate the audience and is an important part of the field of dance. I have delighted in your impressions and gladly welcome your vivid language. This is a most welcomed review. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Shirley Ririe Co-founder of Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company.

Dear Deborah,

It is so nice that I chose the moment after Shirley Ririe had written to you to also reply to you. I was simply thrilled with your review as well, and want to second every word she that wrote. You are an incredible word-smith and have an amazingly evocative style of writing about such an ephemeral art form. The field is indebted to you for your long history of involvement in dance and in writing about the dance.. It is so amazing that Shirley and I and the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company were given the gift of preserving and performing Alwin Nikolais’s works . It has been a very personal way for me to somehow give back to that extraordinary artist a tribute of love for all that he gave to me……the opportunity for audiences everywhere to be able to see his works. The pleasure of working with both Murray Louis and Alberto del Saz on this monumental project has been enriching, delightful and life changing, and I am also very sad that Murray wasn’t there to see the performance.

On a personal note, I saw you for a moment in the lobby speaking to someone before the show, and decided not to interrupt you to say “Hello”. Wish I had. Many, many thanks for such a delicious review.