Big Dance Theater and Noche Flamenca dissect and reconnect narratives.

Tymberly Canale in Big Dance Theater’s Summer Forever. Photo: Paula Court

Once upon a time, dances told their stories the way fairytales and plays did|; they began at the beginning, charted the conflicts that led to a climax, and slid into a denouement. Martha Graham with her Cubist deconstructions of space and time was among the first choreographers to alter the expected narrative flow. After postmodernism worked its wiles on dance, devices of remembering the past, projecting the future, comparing evidently dissimilar works, breaking the fourth wall, and using text and media became common practice. Who could predict what could illumine what?

Big Dance Theater is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year with a two-week season at The Kitchen. Sifting through my memories of the extraordinary dance-theater works created by its artistic directors, Annie-B Parson and Paul Lazar, one element that stands out is the unlikely juxtapositions they visit upon literary works, films, history, dance, and political events. The results are fascinating— neither jolting nor pretentious, and they leave you no time to be puzzled. Afterward, you may wonder, say, how Parson and Lazar came to mingle Richard Nixon’s private Oval Office tapes with accounts of 19th-century “wild child” Kaspar Hauser and archival filmed images of a great kabuki artist. (Plan B, 2004). Or what prompted them to rub together the films Dr. Zhivago and Terms of Endearment, plus the 1970s zeitgeist in Alan Smithee Directed this Play (2014). Yet that friction creates sparks that, in the end, illuminate their sources.

It’s always entrancing to watch the company’s gifted performers—some of whom have been a part of Big Dance Theater for a decade or more—field movement, words, props, and costume changes amid film clips, and scenic elements; they can slip into a character, out of it, and into another with almost shocking dexterity.

I must confess that I would have loved to see a new evening-long work to celebrate BDT’s 25th year, and Big Dance: Short Form (Stick, Sled, Slippers, Hearth, Bundle, Ball) is a collection of six short works, or excerpts from works—a serious (if also giddy) way of revisiting the company’s past, its range, and its priorities. Too, who doesn’t love an intermission that turns into a party with beer, snacks, and games for the audience? Want to play ping-pong? Stick your head through one of the holes in a painted cardboard amusement-park family? Lazar, wearing a wig that could have belonged to an 18th-century gentleman, strolls around conversing with folks over a microphone. A gracious drag queen whose name I didn’t catch plays hostess.

Lazar’s voice-overs provides brief information about each piece’s history, while cast members in puffy white jackets move scenery and clean up. Tei Blow, Joe Levasseur, and Oana Botez provided a score, lighting, and costumes respectively—all terrific.

I must have needed an intellectual warm-up, because I didn’t quite catch what Summer Forever was about, except that the wonderful Tymberly Canale dances with a portable electric log fire nearby and hangs her coat smugly on a hook that doesn’t exist—not noticing when the coat falls to the floor. She ponders a stick. The voice of Cynthia Hopkins (often a vivid BDT performer) mentions a village and a date (did I hear 1590, the year of a terrible earthquake in Austria?), the voices jabbering in the music turn strangely evil, and Canale, after stepping out in some vigorous dancing, finishes in a chair, with a scream, a bit of talking, and a collapse backward.

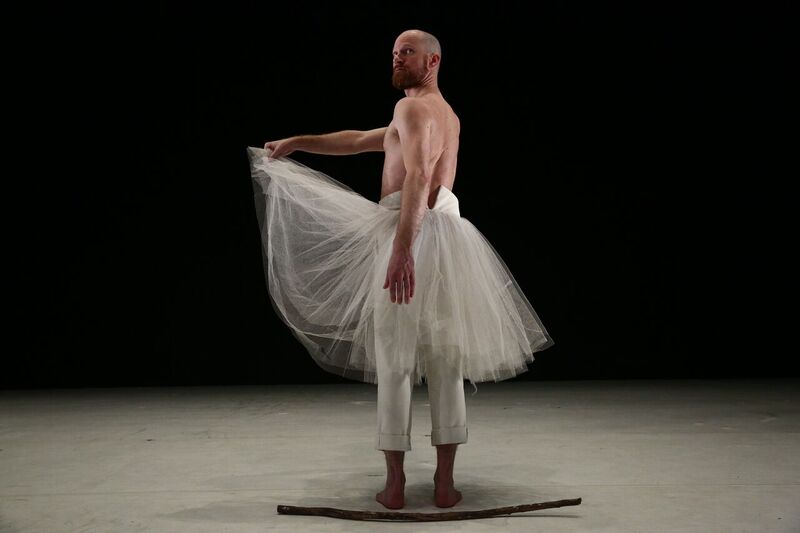

Aaron Mattocks of Big Dance Theater in Short Ride Out (3): He Rides Out. Photo: Paula Court

Aaron Mattocks dances Short Ride Out (3): He Rides Out, a solo inspired by Stravinsky’s Concerto for Two Pianos (Parson choreographed Short Ride Out (2) for ballerina Wendy Whelan, which may be why Mattock’s dons a long white tutu part way through). Mattocks is splendid in the big-dancing solo—vigorous, fierce, and urgent most of the time, yet once grabbing the stick that Canale had used and briefly hobbling like an old man. The only flaw is that this “short” dance feels long.

Parson and Lazar come up with some fascinatingly recondite sources. Who but Parson would create a duet called Resplendent Shimmering Topaz Waterfall based on page 79 of Costume in Face that the program describes as “notebook notations of work by Tatsumi Hijikata transcribed by his disciples?” Who but she would sleuth out references to dancing lessons in Samuel Pepys’ diaries and be inspired to make another duet, The Art of Dancing?

The first duet reinvents the strange, primal images given birth by the founder of Japan’s rebellious postwar dance form, butoh. It’s a mystifying little scene, an interpretation of a text perhaps epitomized by those four words. The stage is dominated by a tin tub, into which a suspended bag of ice melts, one rhythmic drop at a time. Lazar wears rather splendid rags and undergoes a series of states of mind—now strong, now tottering, travelling almost not at all, and letting his face reflect discomfiting emotional shifts. Canale, disguised by a pseudo-Japanese wig, performs various services, slipping the stick into his hand when he needs a crutch; but goes beyond the usual kabuki stage-manager job when Lazar repeatedly staggers backward and needs catching.

Elizabeth DeMent and Mattocks perform The Art of Dancing wearing big curly wigs and shimmering gold pants. Their moves suggest, without copying, the elaborate court dance forms of the 17th century, but the two also mime writing on the floor and flourish booklets containing Pepys’ words. The choice of that text and Mattocks’ occasional delivery of them are deliciously witty. His wife wants dancing lessons. Pepys, looking in on one, tries some steps and is hooked—also rather proud of his burgeoning skill. When his wife wants another month of lessons with Mr. Pemberley (twice a day even!), he confesses to a smidgeon of jealousy. Mattocks plays this beautifully—almost giddily enthusiastic about dancing but a bit slow to get what we are already laughing about. Both dancers end up piping happily on recorders and vogueing as they carry the fireplaces away.

Goats (L to R): Elizabeth DeMent, Aaron Mattocks, andJennifer Liu. At back: Tymberly Canale. Photo: Paula Court

Goats, the most substantial piece on the program, reminds us of what clever fun BDT can wreak on a text—in this case, Johanna Spyri’s saccharine 1881 children’s classic, Heidi. The heroine not only triumphs over orphan-hood in the Alps with a grouchy grandfather, she turns him into a nice guy, romps on the hills with the goatherd, and helps sickly wheelchair-bound Clara to walk again. Prayer is a valued strategy.

The BDT performers have a wonderful time with Goats, and Botez’s layered versions of peasant attire are outrageous. Sweet voices tra-la-la on a scratchy record. Spoken words convey minimal details of the plot. But, true to this company’s own way of layering, DeMent not only plays the invalid Clara, she uses quite another voice and a mastery of the uses and variants of the verb “fuck” when she plays the epically temperamental and frustrated director of an upcoming performance of Heidi. She berates the four others (Canale, Mattocks, Jennie Liu, and Enrico D. Way), who spend a lot of time looking puzzled by her confusing commands and negative blare, although sometimes, they form a ring and do happy dances when playing Heidi and her mountain friends. That is, when they’re not doubling as the characters in the story. One minute, Mattocks is the grandfather, then he’s a stoic actor, then a pal, or maybe a goat. Goats is both silly and clever, staged with fine timing and a lot of brio.

Happy Anniversary, Big Dance Theater! I raise a glass/cup/flagon/wineskin to thank you for past pleasures and look forward to your next big endeavor. How about a sacred legend of India and a bicycle race meeting up? (just kidding. . . I think).

Soledad Barrio in Noche Flamenca’s Antigona. Photo: Chris Bennion.

Sophocles wrote his tragedy Antigone around 441 B.C. In 1942, the French playwright Jean Anouillh wrote an Antigone that didn’t premiere until 1944 because of censorship. A heroine, who defied the unjust and dictatorial ruler who refused burial to her brother, who had fought against him? Not acceptable in occupied France. Martín Santangelo, the artistic director of Noche Flamenca, was impressed by the Living Theatre’s Antigone and spurred on by the suspension of Spanish Judge Balthazar Garzon for his efforts to honor publicly those who had fought against dictator Francisco Franco and to allow families to rebury relatives flung into mass graves.

In his Antigona, Santangelo, like Sophocles, relies on a chorus and a chorus leader who foretell the future and relate the past, but this chorus is flexible—sometimes only three women (Elisabet Torras, Laura Peralta, and Xianix Barrera), but at times swelled by other actor-dancers in the drama. The cast is headed by Santangelo’s wife, the great flamenco dancer Soldedad Barrio, and everyone dances, except for the splendid musicians (Eugenio Iglesias and Salva de Maria, guitars; David Rodriguez, percussion box; Hamed Traore, electric guitar and bass) and the singers of flamenco’s cante jondo, or cante andaluz: Manuel Gago, Pepe El Bocadillo, and Emilio Florido (the Master of Ceremonies). Dancing expresses passion, rage, indecision; it replaces the knives of a duel; it treads the road that leads to death.

Here too, dissimilar elements slide against each other: the classical and the colloquial, Spanish and English, spoken text and written text. Performers may discard one identity and adopt another. But dancing and music bind everything together.

The dark tide of tragedy. Noche Flamenca’s Antigona. Photo: Chris Bannion

The setting is the remarkable interior of the West Park Presbyterian Theater on West 86th Street, where Noche Flamenca presented Antigona for a month last summer and will perform it through January 23. The action takes place on the ample platform before the dais where the altar stands and the low balcony behind that. Santangelo’s direction and Barrio’s choreography unloose a stunning prologue. Between the two recesses that hold the organ pipes, a storm of gray silk (shaken by almost invisible hands) flows onto the stage, disgorging a seething stew of masked figures (that the masks, made by Sydney Moffat, are on the tops of their heads gives them a particularly eerie look). The silk also creates a striking tableau near the end, when Torras, Peralta, and Barrera, like the three Fates, stand behind it with their backs to us, only their unloosened hair visible).

Selected text in English is projected on an overhead screen (Santangelo’s Spanish version is based on the English translation of Sophocles’ play by Dudley Fitts and Robert Fitzgerald). The words are spoken, or sung by Gago, Perez Vega, or Florido in flamenco style, with its harsh cries, its ragged-edged tones, its elaborate trilling and quivering melismas. The heroine’s travails seem dragged from deep in the singer’s guts.

Soledad Barrio as Antigona, with (L to R) Elisabet Torres, Xianix Barrera, Marina Elana, Laura Peralta, and Ray F. Davis (in an earlier cast) as Hades. Photo: Zarmik Moqtaderi

The traditional and the contemporary blend in various ways. The cast assembles in a semi-circle as in a cuadro flamenco, and as Florido introduces each character (“Meet the family”), a performer may take center stage for a recap of his/her history, a brief individual flourish, and to join in a lusty ensemble dance. Oedipus (Carlos Perez Vega); his wife and mother Jocasta (Barrera); their daughters, Ismene (Marina Elana) and Antigona (Barrio); their sons Eteocles (Robert Wilson) and Polyneices (Carlos Menchaca); Creonte (Gago); his wife, Eurydice (Torras); Haeman, his son and Antigona’s beloved (Juan Ogalla); Tiresias (El Bocadillo). All are onstage in one way or another much of the time, whether dancing, singing, speaking, gesturing or crying out. So, after several farcically quick deaths by way of background, guitarist de Maria shouts, “Hold your horses people, so much grief! Let us dance and sing before the tragedy begins!” And eventually they do—screaming words like “sangre!” over and over while lights turn the stage red.

The poetic text is countered by occasional contemporary talk. This Ismene is not the gentle sister of Sophocles’ tragedy. Elana plays her (in part) as an antagonist to Antigona, channeling a Valley girl as she sits and files her nails, while bringing us up to date (“ Hi everyone. I am Ismene.”) More intriguingly, the battle-to-the-death by the brothers, Polyneices and Eteocles is presented as a dance-off, with Menchaca whipping off turns and creating a fusillade with his feet, and Wilson, whose background is in hip-hop, interpolating arm and torso ripples plus one-armed handstands. To accompany this, Traore wields his instrument with a rock guitarist’s rhythmic fervor.

There are occasional confusing moments. Barrio takes off her shoes and is drawn away on a long piece of fabric symbolizing the river Acheron but, no, she hasn’t yet committed suicide. That comes later. Creonte, whose character is linked with that of a vainglorious dictator, such as Franco, wears a matador’s hat at his inauguration, which is punctuated by attacks between a bullfighter (Menchaca) and a bull (Elana using a stool for horns). Still the theatrical excitement and passion that Antigone’s marvelously skilled, whole-hearted performers ignite onstage and among the spectators is thrilling. The music—bulerias, tangos, soleares, seguiriyas—and the rhythmic clapping that drives it deepen the darkening moods and fuel the dancing.

Soledad Barrio and Juan Ogalla in Antigona. Photo: Zarmik Moqtaderi

Barrio is at the heart of the drama and the show. She rarely speaks, but her acting is sensitive and nuanced, and her dancing magnificently reveals sorrow, frustration, grief, and conflicting desires. She steps challengingly into them, whirls in their winds, stamps them with her feet as if they were flaming up around her. Dancing is a peril that she wraps around herself and flings away, like the shawl that a Spanish dancer often wields. This Antigone is a strong woman who risked all and faced down a regime because burying her brother was a moral imperative. Her longest solo is before the cave where she is to be entombed alive and where she hangs herself. Barrio’s powerful body, her fiercely concentrated face, and her feet beating out a complexity of rhythms tell us how arduous this journey into death must be. Yet there are moments of joy when she and Haemon dance together one last time (he has been unable to save her); the accompanying lyrics come from Sophocles’s “Ode to Love.” And here Ogalla has his finest moment as an impassioned and skillful master of the nuances of flamenco.

Santangelo and his colleagues have put together a remarkable show. Antigona reminds us in the most poetic of ways how necessary it is to speak out against injustice, whatever the risk.