Ann Liv Young’s Elektra at New York Live Arts, January 20-30

Ann Liv Young’s Elektra. Foreground: Marissa Mickelberg. At back (L to R): Lovey Ailish Guerrero, Vanessa Soudan, Daniel Borg, and Nessa Norich. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The chronically grumpy comedian W.C. Fields advised fellow actors never to work with children or animals if they wanted the audience’s attention full-time. He knew what he was talking about, but Ann Liv Young is a creatively flagrant disregarder of many conventions. During her new Elektra at New York Live Arts, my gaze occasionally wandered to Young’s pretty eight-year-old, Lovey Ailish Guerrero, sitting watchfully at the back of the action. Even more often, I looked at Daisy, a piglet, whenever her handler (Marissa Mickelberg) deposited her in the circular performing arena surrounded by a two-foot-high wire fence and backed by a semi-circle of six glittery white drapes (artistic collaborator: Annie Dorsen). Tail wagging, Daisy rooted around in the sand that filled the giant pen as if she were hunting truffles, her snout turning quite white from her efforts. Her occasional snorts, grunts, and squeals provided a nice obbligato to the speeches and the singing, plus the recorded pop songs in Michael A. Guerrero’s sound design.

Amid the obstreperous, transgressive, carefully orchestrated craziness of Young’s Elektra (vividly lit by Lauren Libretti), you might view Daisy as digging for relics from the battlefield of Troy, while the members of the ill-fated House of Atreus squabble, kill, seduce, and die. Do not, by the way, think you can easily follow the characters depicted in myth and Greek tragedy: Elektra (Young); her mother Clytemnestra (Bailey Catherine Nolan); her brother Orestes (Charley Parden); her sister Chrysothemis (Vanessa Soudan); and the ghost of her sacrificed sister, Iphigenia (little Lovey). These extravagantly dramatic performers are wading in a postmodern marsh, within which contemporary issues twist and swim their way through history, music, and literature. Parts of Sophocles’ text are heard, but words from Tracey Thorn’s “Oh, the Divorces!” might well fit Agamemnon’s fatal affair with Cassandra, whom he brings home from Troy (“Who’s been caught/ Out in somebody’s bed?).

Elektra Cabaret. Foreground (L to R): Marissa Mickelberg, Ann Liv Young, Nessa Norich, Lovey Ailish Guerrero. At back (L to R): Bailey Catherine Nolan, Daniel Borg, Vanessa Soudan. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

It’s a part of the plan that an array of extremely interesting little objects accrued by the company is on view in the lobby. And for sale. My companion bargains with the salesperson with the white-painted face, and in seconds, a tiny brooch of fake diamonds has been re-purposed on her neck scarf. Just so, the performers—in addition to being “themselves” (swigging water, sitting and watching, addressing us, etc.)—redesign their appointed roles and maybe those of avatars in a handier past than ancient Greece.

Even the intermission between Elektra and Young’s earlier Elekra Cabaret offers an over-the-top assaultive performance. Those who lingered in the lobby missed be-wigged and sex-hungry spiritualist (Nessa Norich) and her baffled stooge (Daniel Borg), holding the limp ribbons with which he’s been whipping the air.

“Over the top” is where Young likes to roam. You can’t help but be enthralled with how far she’s prepared to go and the whopping imagination she brings to her stew of adultery, murder, incest, and sacrificed women. At first, it seems as if the post-intermission part of the evening repeats much of what you’ve understood from the first part, even though it’s more circus-y and brings out other aspects of the characters (now wearing outfits made of blue denim). But how can you not respond to such moments as Guerrero getting down to belt out Eminen’s “Monster” song with her mom, or Mickelson (now dowdy, without makeup, and wearing a straggly blond wig) pleasuring herself as she delivers a speech, while standing partially concealed behind the seated Parden, who slowly and rather quietly wilts under the pressure of her other hand on his head.

Ann Liv Young’s Elektra. Vanessa Soudan (on chair), Ann Liv Young, and (at back) Charley Parden. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

There is dancing in Elektra. Young and Soudan, both wearing black, form a mini chorus line and do severe precision stuff. Nolan in her bulky, yellowed satin gown (ca. 1910) joins them. They assume ballroom stances (while Harry Belafonte’s mellifluous voice sings “Day-O”). They lash their hair furiously around. They also sing. The two “sisters” also at some point join in some stylish moves; linked together on the floor, they split their legs to reveal what we’ve understood from the start: no underwear. Somewhat later, Soudan and Nolan exhibit killer patty-cake—as swift with their hands as Young is with her mouth when she stands and delivers what could be three pages of text at warp speed. Parden flexes his muscles and shows his hip action explosively. Near the end of the Elektra Cabaret part, everyone’s furiously doing his/her own thing.

The recklessness of some scenes can hit you in the gut. The fearless Soudan attempts to pose on a chair (or is that not what she was trying to do?). Whatever her motive, she repeatedly falls or flies off it, knocking the chair down in the process and having to set it up so again. In what I take to be Elektra’s attempts to persuade Orestes to kill their mother, Young keeps clamping herself onto Parden, wrapping her legs around him in unlikely ways, and hanging on until he, swaggering doggedly around, makes that almost impossible (or accedes to her demand). For this, “Alabama Bound” yields to tinkly piano sounds.

In another early scene, Soudan violently attacks Young who’s been sitting at the back holding an erect baguette. One swipe by Soudan, and the bread is cut in half. Determined to demolish the loaf (whatever it represents) and rid the family of it, she wrestles with the resisting Young, clawing clumps of bread out of her mouth and scattering them. By the time the two have dropped that and moved on to some other pursuit, Soudan’s dress is tattered and hanging off her.

Charley Parden as Orestes copes wit his sister Elektra (Ann Liv Young). Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The props don’t have an easy life. Nolan punishes a dead branch decked with small white rags. In Elektra Cabaret, Soudan, utterly transformed into a “shy” and grimacing version of Chrysothemis, beats a fallen bicycle to death with a pogo stick. Blood makes an appearance in a tableau near the end of the first part of the show. A sword is plunged into Clytemnestra; a blackout; a scream. When the lights come on, there she is supine and half-upended; her legs are braced against Orestes’ chest, a cloth covers her upper body, and blood runs down the slant of her torso (linking beheading with the menstrual cycle?); her son holds her head aloft; her daughters crouch beside her.

So much to look at, to parse, to react to. So many fears (assault weapons, loss of beauty, betrayal, relationships gone tragically awry). Elektra has something in common with the display in the lobby: The beautiful and the garish, the superficial and the deep, the here-and- now and relics of the past butt into each other, wreaking havoc as they go.

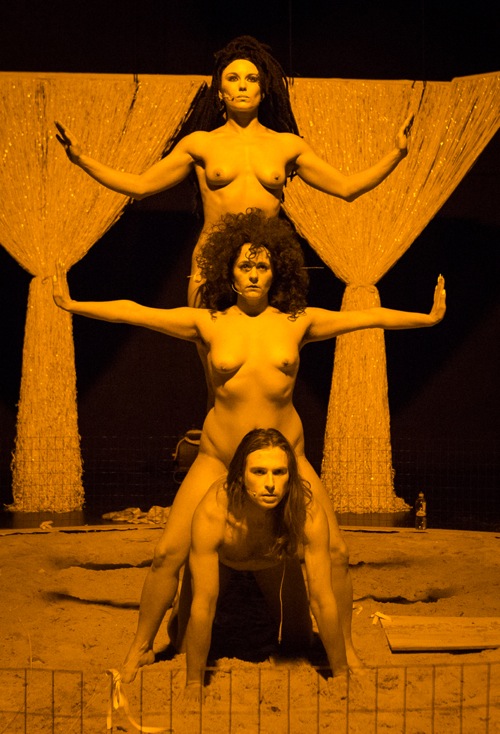

Top to bottom: Vanessa Soudan, Bailey Catherine Nolan, and Charley Parden in Elektra. Yi-Chun Wu