Jawole Willa Jo Zollar’s Urban Bush Women celebrates its 30th Anniversary.

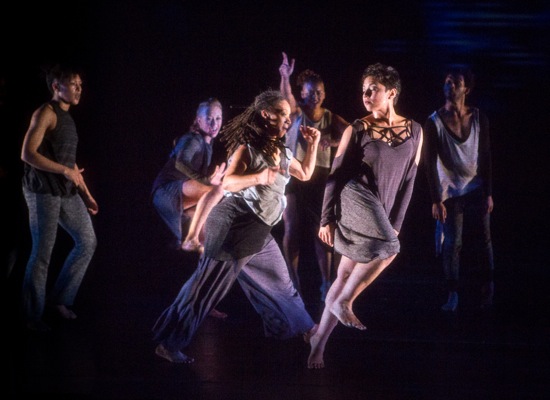

“Side B: Freed(om)” of Urban Bush Women’s Walking with ‘Trane. Foreground: Amanda Castro. At back (L to R): Stephanie Mas, Love Muwwakkil, Du’Bois A’Keen. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

How time dawdles when you’re young! At six years old, looking back on what it meant to be three? That was ages and ages ago. After you pass sixty, you may find yourself thinking that an event took place just a few years back, when it happened two decades earlier. Luckily, progress and change help fasten you to accurate counting.

What promoted the above musing was the 30th anniversary season of New York’s Urban Bush Women at the BAM Harvey. I saw the company founded by Jawole Willa Jo Zollar at LaMama in 1985 and was struck by the lack of artifice in the performing, no matter how dramatic the subject, and those six African American women including Zollar could cut loose vocally as well as physically.

A scene in her River Songs has stayed with me for three decades; I’ve mentioned it several times before, so greatly did I cherish its theatrical daring, its simplicity, and the succinctness with which it conveyed so much. Here’s what I wrote in the Village Voice in 1965:

“A girl (Karla McFarlane) curls in the crook of another woman’s leg while the woman (Robin Wilson) works on her hair. ‘Ne, ne,’ she chants dreamily, while her comb digs into the scalp, hard. The “child” screws up her face and body with the pain; then, as the mother rubs soothing ointment into the sore places, she relaxes back against that supporting knee, is almost asleep by the time the hair is pinned back up and the headscarf is tied on. They walk off with their arms around each other.”

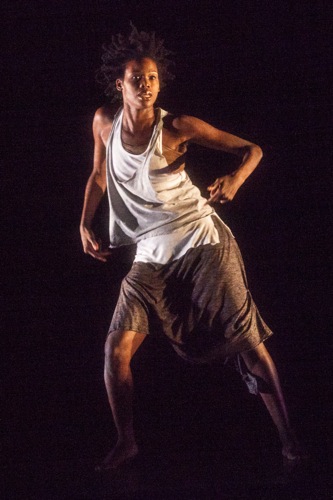

Tendayi Kuumba in Urban Bush Women’s Walking with ‘Trane. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Urban Bush Women has remained a small company, and its repertory has continued to focus, for the most part, on African American themes and concerns. Other choreographers, such as Nora Chipaumire, Camille A. Brown, and the late Blondell Cummings have contributed new or existing works to UBW’s programs. The scenic elements and costumes are now more ambitious, but the dancers are as strong and forthright and go-for-broke intense as those dancers of thirty-plus years ago; finely trained and accomplished as they are, they still seem to value wildness and naturalness over sleekness and glamor, and the choreography made for them brings that out. They may be as powerful as the superdancers of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, but they downplay their virtuosity—or rather, translate it differently.

The new piece that celebrates UBW’s 30th anniversary is Walking With ‘Trane, and the title shows Zollar’s affection for the music of the innovative jazz great, John Coltrane. Philip White and George O. Caldwell, the two composers whose contributions animate the dance, are not playing music associated with Coltrane; they have digested his influences, his spirit, and the traditions he drew on in their own ways.

Chanon Judson in “Side A” of Walking with ‘Trane. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Walking With ‘Trane is divided into two halves, “Side A: Just a Closer Walk with ‘Trane” and “Side B: Freed(om)”—calling to mind the 78 and 33 1/3 RPM records on which Coltrane’s music was heard in the 1950s and 1960s. The choreography for both sections is by Zollar and Samantha Speis in collaboration with the dancers, but the costumes differ. For “Side A,” Helen L. Simmons-Collen’s monochromatic costumes—street clothes with the give-and-take of dance attire—personalize the cast members.

White’s composition for vocals, saxophone, bass, keyboard, and drums, plus electronic manipulation begins with a humming sound and burgeons into a beautifully controlled composition that also allows wildness to erupt and is willing to fall silent. The big opening dance solo performed by Chanon Judson lays out all the elements that UBW values. It’s get-down dancing that hints at African roots, but tall, lanky Judson’s legs fly through space, while her body undulates, her shoulders and head roll, and her sinuous arms curl around the air or pat it down. This is dynamically rich stuff: she can focus on small moves as well as bigger, more volatile ones. She may accent her rhythms with a big jump or two or by slapping the floor with her feet. But never does she show you a preparation for a major move or throw away what might be considered a minor one. Her body sings with the music without copying every move it makes.

Urban Bush Women in “Side A” of Walking with ‘Trane. (L to R): Courtney J. Cook, Stephanie Mas, Samantha Speis, Tendayi Kuumba, Amanda Castro, and Du’Bois A’Keen. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

What develops is kind of a dance party without party-time behavior. The other dancers enter gradually as watchers and joiners; they’re developing something together. Here come Love Muwwakkil, Amanda Castro, Tendayi Kuumba, Stephanie Mas. Pretty soon appear Courtney J. Cook (a tall one), Du’Bois A’Keen (An Urban Bush man, who knew?), and finally Speis. I like the way they can all be different at the same time or, as the piece progresses, surprise you by falling into unison without dropping a stitch.

The atmosphere is not without its perils. Russell Sandifer (lighting design) and Wendell Harrington (video design) create very real-looking images of roiling black clouds, which resolve not into a clear sky, but into a projection of vertical blue panels. All kinds of life exist in this changeable world with its echoes of blues, bebop, and more. One minute the dancers are striking poses and holding them for a second; the next minute, they’re walking slowly along bent over, as if they’d become their own grandmas. They watch Speis as she dances in a corner, her feet skittering in place and drumming the floor when she sits. If she gets too close to the others, they lean away from her.

Performers recline to take in the view, sway, move in desultory ways, stagger. Three gather upstage, feinting and responding. Two get on their phones (“Why don’t you answer when I call?”). All eight of these terrifically gifted performers seem at home in the shifting atmosphere of music and light; they respond to climate changes with flow, the way you’d reach a hand for a dishtowel when someone offers you a wet plate and still keep the conversation going.

Tendayi Kuumba (L) and Du’Bois A’Keen in “Side B: Freed(om).” Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Caldwell’s music for “Side B: Freed(om)” was inspired by Coltrane’s 1965 recording, A Love Supreme, and it’s Caldwell himself, who appears in a white suit, sits down at an onstage piano, and cuts loose. He’s an amazing musician whose nimble fingers are as much a part of what you want to watch as the dancers are.

Now most of the projections are less abstract. They show vertical red shapes that together suggest a theater curtain, then a big theater with rows of balconies, silhouetted musicians, a slide of Coltrane’s face. Later the lighting will create pools to trap the dancers and make them shine brighter.

On the run (L to R): Tendayi Kuumba, Amanda Castro, and Du’Bois A’Keen in Urban Bush Women’s Walking with ‘Trane. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Bright they are. They’ve been able to spruce themselves up during intermission, and Simmons-Collen’s “Side Two” costumes are very smart combinations of white, red, and black. They seem to be almost always on the run, sometimes in a pack, but encounters and solo turns are a big part of the choreography. Unison doesn’t hold them for long; they bust out of it. They spar, they cluster, they scrimmage, they gather and breathe together. Sometimes, they just want to look on while Caldwell performs his intricate, driving magic on the piano. At the end, after a high pitch of craziness in both music and movement, everything rises to a level of blissful stability. That’s when the curtain falls.

Best thoughts and images you have for urban dance!!!