The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater opens its City Center run, December 2 through January 3.

During the curtain call at City Center that followed the world premiere of Robert Battle’s Awakening, the twelve members of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater joined the audience in clapping enthusiastically for him. Sweaty, their faces alight, their hands slamming together, they showed their support and their affection. This was the first new dance made for the AAADT by its artistic director.

Since Battle took that position four years ago, he has shown that he understands both what’s best to preserve of the company’s heritage and what new blood to bring in. He’s challenging the dancers—among the world’s best—as well as broadening the audience’s perception of the company. This season, among the two dozen dances on view, there are additional world premieres—by Kyle Abraham and Ronald K. Brown, choreographers who’ve created pieces to the repertory before, plus Paul Taylor’s Piazzola Caldera and a new production of Ailey’s 1958 Blues Suite (a dance that appeared at the very first performance at the 92nd Street Y of Ailey’s then small pick-up group). Rennie Harris’s Exodus, which premiered during the June season, is also on the schedule.

Robert Battle’s Awakening. (L to R): Samuel Lee Roberts, Elisa Clark, Jacquelin Harris (in front), Demetia Hopkins-Greene, Yannick Lebrun, Rachael McLaren, Belen Pereyra, Daniel Harder, Jacqueline Green (in front), Kanji Segawa, Michael Francis McBride. Photo: Paul Kolnik

Awakening begins promisingly. Excitingly. In darkness streaked with light, individual dancers race past in various directions. All eighteen are dressed identically (by Jon Taylor) in white pants and tops. The first selection of music is a recording of John Mackey’s 2007 Turning. Written for a wind orchestra plus percussion, it’s cataclysmic: screaming brasses, crashing melees followed by abrupt silences. The running dancers gradually fall into contrapuntal patterns, some of which evoke veering around city corners and following narrow streets; a line of several dancers may run onto the stage and almost immediately twist to run off it, their feet actually skidding a bit as they make the turn. Amid the music’s blare and clamor, they finally (and briefly) form a line that stretches from the front to the back along a side edge of the stage.

But chaos is always threatening, even though some of the passages are repeated intermittently. A couple of times, for instance, the dancers, form a clump and look upward, as if for a sign; they start to unwind the cluster, only to break away—thrusting, running, spinning. Sometimes they rise from their knees leaving a single dancer briefly prone. Sometimes they flutter or shake as if the earth under their feet were punishing them. One man (Jamar Roberts) proves to be a leader of some kind.

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Robert Battle’s Awakening, Jamar Roberts center. Photo: Paul Kolnik

“The Attention of Souls,” the third movement of Makey’s Wine-Dark Sea: Symphony for Band (2014) succeeds Turning, and it is lighter in tone (although still fierce); the higher wind instruments, almost perky, argue with deeper more dissonant voices, and, in the end, what might be a sweet melody is buried by a climactic explosion, out of which only a few quiet tones survive. Lighting designer Al Crawford has created a backdrop in which rows of tiny white points of light appear, multiply, diminish, reconfigure, and flash, perhaps to convey an atmosphere that I can’t fathom. Once, dimmer irregular ones appear at the top, suggesting something akin to a night sky.

Battle eschews literal drama in favor of telling structures, and he deploys his marvelous, driven cast skillfully in small groups and tumultuous ensembles. I missed getting a gradual sense of the awakening that the title encapsulates, a transition from chaos and uncertainty to. . .what? I’m not sure. (At the end of Awakening, Roberts has collapsed and crawled toward a corner; the others circle him, reach toward him.) Perhaps as the work develops through performance, Battle and the dancers will clarify its journey of shifting moods and qualities.

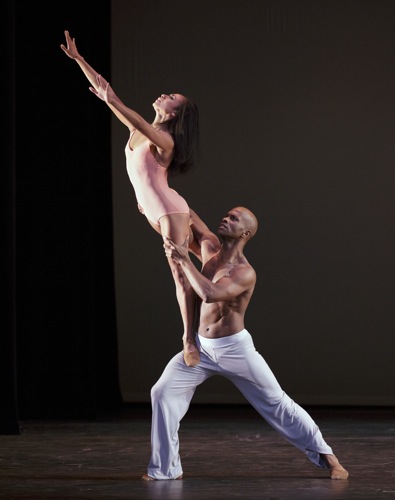

Linda Celeste Sims and Glenn Allen Sims in the pas de deux from Christopher Wheeldon’s After The Rain. Photo: Paul Kolnik

Battle has brought into the AAADT pieces made for other companies and dancers. One of these, programmed the night Awakening debuted, was the beautiful duet from Christopher Wheeldon’s, After the Rain, which was created in 2005 for Wendy Whelan and Jock Soto. The ethereality of the music, Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel, corresponded to Whelan’s lightness and simplicity. Soto seemed to be trying to hold an innocent spirit. Subsequent casts naturally bring their own personas to it. Among the Ailey couples, Linda Celeste Sims, beautiful and devoted as she is, makes the woman’s role earthier and more dramatic; this is in part because she uses her extraordinarily flexible spine to arch further into many of the movements. So the duet looks somehow more effortful, despite the attentiveness and simpler demeanor of her excellent partner-husband, Glenn Allen Sims.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Talley Beatty’s Toccata. (L to R): Sarah Daley, Samuel Lee Roberts, Linda Celeste Sims, Matthew Rushing, Hope Boykin, Michael Francis McBride, and Demetia Hopkins-Greene.

Photo: Paul Kolnik

This particular program opened with Toccata (excerpted from Talley Beatty’s 1964 Come and Get the Beauty of It Hot). Beatty (1923-1995) was himself a marvelous dancer and could be a demanding choreographer (tyrannical, said dancers who worked with him in the 1950s). He knew show business, nightclubs, jazz, Afro-Caribbean, and modern dance traditions and deployed them all in forging a black identity in contemporary dance. The AAADT has shined up the choreography and downplayed gender by dressing all sixteen dancers in white tank tops, black pants or tights, and black jazz shoes (costumes by Matthew Cameron). The piece is stylish, clean as a whistle, and effervescent in its energy—a show-bizzy opener.

Toccata takes its name from a piece by Lalo Shifrin, here heard in a terrific recording by Dizzy Gillespie and his Orchestra, and Beatty’s choreography offers hip-swinging steps, high kicks with the foot flexed, sailing turns in attitude, and flying lifts. Here three treasured dancers (L.C. Sims, Hope Boykin, and guest artist Matthew Rushing) take center for a while, and four men show off. Most of the time, the dancers face the audience and show us their ebullience and their pleasure in churning up this dance.

The evening ends with. . .wait for it. . .Revelations. This was one of several performances during the first week of the company’s winter season when the traditional religious songs were performed live, giving the dancers an extra lift. How many times I’ve seen this dance, loved it, and despaired for it since its birth in the 1960s! We rightly adore it, but spectators also adore showing that they’re primed to applaud at the certain moments, even if that’s not appropriate for the graver parts of this exuberantly spiritual masterwork. Why oh why, I mutter to myself, must Sarah Daley turn a rapt fall-back against Yannick Lebrun’s supporting arm into a backbend that rouses the audience to clap?

But I’m as thrilled as anyone by the desperate virtuosity of Collin Heyward, Sean Aaron Carmon, and Chalvar Monteiro as they flee the wrath of God in “Sinner Man,” wishing only that they could always make their multiple spins look like tornados of the soul. And I admire greatly G.A. Sims’s taut restraint in the floor-bound solo “I Wanna Be Ready.” Ailey may have taken those moves that test the performer’s stomach muscles from the Lester Horton technique he was bred in, but done simply and with eloquence, they suggest a man wishing to lift as much of himself as possible off the floor and closer to heaven.

Take a look at the late Dudley Williams performing this solo in 1986, and you’ll see what I mean:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3bADQzyg00g

As the fan-wielding women in their Sunday-go-to-meeting yellow dresses and floppy hats assemble—ready to praise God and chat with their neighbors—I flash back to Williams, who died in last June. He had a long, rich career performing wonderfully for Martha Graham, Beatty, Ailey, and, in recent years for Paradigm, a company formed by him, Carmen De Lavallade, and Gus Solomons jr. He was a treasured dancer in AAADT for 42 years, and later, at various galas and special occasions, he could be found onstage in Revelations’ finale, “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham,” usually centerstage among the men. Trim as always, he was so incisive, so cool, so anchored in the music that he made the other guys—all of them superb dancers—look just a little bit sloppy.

Oh those dancers! How many times have they made the finest works in the repertory glow and resonate and the less good ones acquire a vigor and sincerity that all but veil their flaws? Don’t even bother trying to count. These men and women communicate an appetite for dancing, and we go home replete.

;