Twyla Tharp ends her 50th Anniversary Tour in New York City.

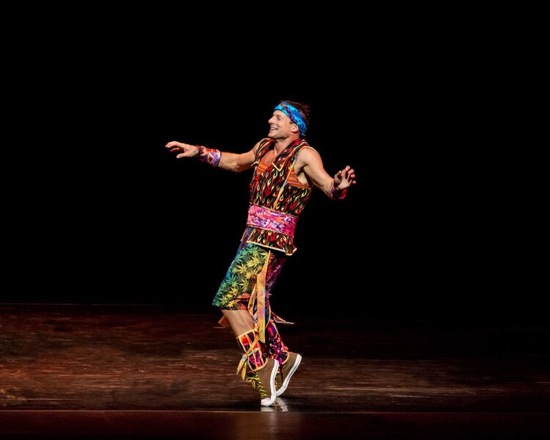

Is that a familiar leg? (L to R): Ron Todorowski, Amy Ruggiero, and John Selya in Twyla Tharp’s Yowzie. Photo: Ruven Afanador

Twyla Tharp premiered her first work, Tank Dive, on April 29, 1965, in room 1604 of Hunter College’s Art Department (where she was not a student). It was the only dance on the program and lasted four minutes, which she considered to be the longest amount of time she thought she could fill to perfection. Besides, she noted in a 1976 interview, the event was free. Who would have dared complain?

This year Tharp celebrates her 50th anniversary as a choreographer. Over the years since 1965, she has—like one of her heroes, George Balanchine—not only made dances for her own company, as well as for others; she choreographed Broadway musicals; and worked in film and television. During the early part of her career, she could be identified as an obstreperous postmodernist breaking the mold of conventional structure, and if you didn’t like what she made, that was not a problem she cared to address. Her onstage manner and that of her dancers was severe. Eventually, she decided that communicating “something to everybody” (her words) could be rewarding; eventually her dancers smiled occasionally.

Some of my many favorites among her pieces are those in which she pondered, questioned, and explored what ballet, popular dance, and modern dance might have in common and the ways in which they differed. I think back on her The Bix Pieces (1972), with its lecture-demonstration component; Deuce Coupe (1973), in which, initially, her dancers and members of the Joffrey Ballet shared the stage; and Push Comes to Shove (1976), which dissected the virtuosity of the recently defected Mikhail Baryshnikov and taught him how getting down could hobnob with bolting into the air and spinning indefinitely. In the culminating work in this group, the brilliant In the Upper Room (1986), set to a score by Philip Glass, two “teams” (one wearing sneakers, the women in the other sporting red pointe shoes) showed their stuff, met, mingled, and danced their way to heaven.

The permutations of the style that she developed in work after work could result in fierceness, as they did in the battle scene she created to Billy Joel’s “Saigon Song” in her greatest musical, Movin’ Out. And near-vaudevillian wit and comedy infused other creations. Her approach to lyricism could, without sentimentality, break your heart. You see these qualities and more in the two new works that make up the bulk of the program that she and a company of terrific dancers put together some months ago. Its tour ends with a brief New York season, presented by the Joyce Theater at the former New York State Theater.

In both Preludes and Fugues and Yowzie, as well as in First Fanfare and Second Fanfare, which precede each of these, you see a tribe of extraordinary dancers, who give every step, every prodigious burst into the air, every fusillade of rapid footwork the air of ease. No big-deal preparation, no watch-me-now presentation. Tharp veteran John Selya can launch himself from a stroll into an uncanny twisting leap with the nonchalance of a man switching on the morning coffeemaker. These dancers have impressive and impressively variegated backgrounds; some have danced with major ballet companies, others come from modern dance, still others have Broadway credits. All of them can do almost anything—from Selya and Rika Okamoto (once in Martha Graham’s company) to Reed Tankersley, who graduated from Juilliard in 2014.

First Fanfare brings the dancers on and off the stage in a series of amicable sorties. The recorded music, John Zorn’s “Antiphonal Fanfare for the Great Hall,” blasted out by seven members of the Practical Trumpet Society, summons them in batches. Tharp is introducing us to the dancers, as well as preparing us for the works to come. So Matthew Dibble and Nicholas Coppula, the first to take the stage, later reprise their first material and add a battery of fouettés, whipping that outstretched leg around to froth the air (I’ve forgotten whether they both did this echt-ballet feat or only one of them). On the less elegant side, Daniel Baker wrenches his body around and skids across the floor. Tankersley sports like a bumblebee around two tall, long-legged beauties you might recall from the New York City Ballet (Kaitlyn Gilliland and Savannah Lowery). All the dancers show us their speedy, pointy footwork, as well as their shrugs, collapses, and “what’s that all about?” gazes.

Tharp has offered a terse introduction to the program: “Simply put, Preludes and Fugues is the world as it ought to be, Yowzie as it is. The Fanfares celebrate both.” I’ll stave off arguing with this for later. She mined the 48 preludes and fugues that make up J.S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, Books I and II and chose a reasonable number (more preludes than fugues), shifting the order as she pleased from recordings by David Korevaar and by Angela Hewitt. Bach composed these pieces as exercises for fingers in all the major and minor keys, but what exercises! Tharp sees dancers as heroes, their discipline and skills and trust of one another standing for an ideal world. She and Johann Sebastian are well matched.

Twyla Tharp’s Preludes and Fugues. L to R: Daniel Baker, Amy Ruggiero, Nicholas Coppula, and Eva Trapp. Photo: Ruven Afanador

The choreography for Preludes and Fugues doesn’t announce itself, however, as idyllic or “beautiful” all the time. Nor is it “storyless”(a term Balanchine preferred to “abstract”) as, say, In the Upper Room is. It can be bold, sweet-natured, smooth, bouncy, witty, rowdy, dramatic, often at practically the same time. And all of it displays Tharp’s remarkable gift for varying dynamics; she captures marvelously the shifting speeds, directions and emphases that mark our lives. Her musicality is fine-tuned to musical structure, but she’s not wedded to the rhythms— pouncing on them occasionally, marking their high points, but often dipping into them the way you might dip into a stream when you walk along its banks, sensing its changes in flow.

The first of many sections in Preludes and Fugues is a duet for Selya and Savannah Lowery. Lighting designer James F. Ingalls gives them a bit of blue, and they behave like a couple of people alone and tender in a ballroom. Often holding each other in the traditional grip, they swirl in the music in ways both fluid and complex, mixing in a whiff of a tango here, a polka there, with a non-waltz waltz as a touchstone. In contrast, the second section, a duet for Dibble and Amy Ruggiero is rapid enough to render them giddy; a flurry of lifts, and they’re away.

Some of the moves are eccentric. Tankersley lowers Ramona Kelley to a prone position one jerk at a time, and men sling women around in ways that can be peculiar as well as breathtaking and intimate. There are a few allusions to courtly behavior (Baker kisses Okamoto’s hand, although neither of them makes a big deal of it). Human urges enter the picture. Now it’s Ron Todorowski who’s smitten with Lowry and Gilliland, who stalk in at one point, and he can’t make up his mind between these goddesses. They’ll have none of him, even though he kneels and opens his mouth in a silent howl; he exits shuddering and twitching.

Twyla Tharp’s Preludes and Fugues. L to R: Daniel Baker, Amy Ruggiero, Rika Okamoto, Matthew Dibble, Ron Todorowski, Savannah Lowery, Kaitlyn Gilliland, John Selya, Nicholas Coppula, Ramona Kelley, Eva Trapp, Reed Tankersley. Photo: Sharen Bradford – The Dancing Image

In Preludes and Fugues, Tharp, as is her wont, often presents an image of a busy society, with trios or quartets or duos engaged in different simultaneous activity. That this density looks energized instead of confusing may be attributed to her masterly choreographic skills. Discussing her Brahms-Haydn in a 2001 interview, she pointed out that “there is a true support system between the foreground, the middle ground, and the background” and added that it took her twelve years to learn how to manage triple counterpoint like that. She also expertly sneaks unison out of complexity. Suddenly in Preludes and Fugues, four dancers stand shoulder-to-shoulder. Suddenly all the men are together facing all the women, and you can take in the full range of muted colors in Santo Loquasto’s semi-Grecian dresses. And suddenly, near the end, to that prelude of Bach’s that Charles Gounod poached as the underpinnings for his “Ave Maria,” all twelve dancers are in a circle, spinning in place and spinning around it, their palms pressing down on the air.

Preludes and Fugues finishes back where it began, with Selya and Lowery, alone together with the night and the music.

O.K. so I don’t quite see this amazing piece as presenting the world as it ought to be. And I don’t see Yowzie as the world as it is. The latter is a gutsy, bawdy, beautifully organized vaudeville of behavior that’s delivered with heightened theatricality. I get what Tharp is driving at, but if this represents the world as it is, we’d all die young, drained by our efforts.

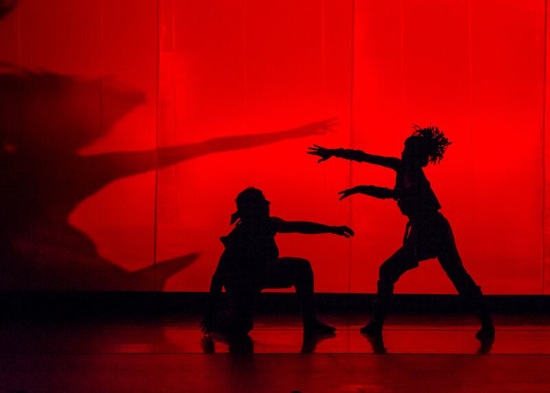

An image from Second Fanfare: Matthew Dibble and Rika Okamoto. Photo: Sharen Bradford – The Dancing Image

After the intermission, she warms us up with Second Fanfare, which she set to Zorn’s “In Excelsis,” performed by the American Brass Quintet. The dancers appear in rowdy silhouettes against a glowing red curtain, and loom behind it as giant shadows. It’s a shock when they appear in Yowzie wearing astoundingly gaudy costumes by Loquasto that give a new slant to the term Broadway applies to its chorus dancers: gypsies.

Tharp has learned much from her work in musical theater, and these dancers know how to time a glance, make a shrug count, do a double take, play drunk, exit with an implied wink. They’re not playing to the audience in predictable ways, but they are drawing on theatrical traditions. And they have characters to play and stories to tell. The music takes us back to another era. Three of the seven recorded selections played by Henry Butler/Steve Bernstein and the Hot 9 are by Jelly Roll Morton; one, “Viper’s Drag,” is by Fats Waller, and Wesley Wilson wrote “Gimme a Pigfoot.” Butler contributed the remaining two selections.

Tharp’s Yowzie. In front, upended: Rika Okamoto. L to R: Kaitlyn Gilliland, Amy Ruggiero, Matthew Dibble, John Selya, and Ron Todorowski. Photo: Sharen Bradford – The Dancing Image

Talking about this 50th Anniversary tour, Tharp mentioned that she incorporated bits of material from earlier dances in Preludes and Fugues. I couldn’t identify these, but I did see Okamoto in Yowzie doing a superb imitation of Tharp’s drunk solo in Eight Jelly Rolls (1971), while a solemn chorus parades behind her in a kind of dead march, just as it did in that epic early work. Later, I spot her wandering through the throng with the ape-like waddle I associate with Deuce Coupe and the Beach Boys’ song “Alley Oop,” which figured in it.

However Okamoto, unlike Tharp in 1971, has company on her bar crawl. Dibble, her partner, is initially as unsteady on his feet as she is, and a bit unsure as to his sexual preferences. Selya (wonderfully deep-down jazzy) and Todorowski (terrific in his rubbery aplomb) are a threesome with their sharp-witted gal-pal Ruggiero. Todorowski sinks into a split; Selya is shocked and awed. But the two men air swishiness as well as good-natured lustiness, and they corral Dibble, who eventually finds his way back to Okamoto with no hard feelings on anyone’s part.

I couldn’t hear what Selya was yelling into a pretend microphone at one point, but I could admire Dibble’s being fabulously stable in a balance on one toe that his temporarily unstable character probably had to be drunk to even attempt. The dancers have a ball in Yowzie, even the relatively sane Coppula, Tankersley, and Eva Trapp, as well as Kelley and Baker. Gilliland and Lowery swan around in big hats, evidently slumming. Everyone dances like crazy and handles everyone else with an athletic zest that borders on risk.

If Tharp has decided that entertaining an audience is part of what she wants to do, she certainly succeeded in Yowzie, but if you wanted to see it as something deeper, you could imagine a happy-ending Orpheus-Eurydice tale with the roles reversed, starring the marvelous Okamoto and Dibble. The Fates, or maybe the Furies? Selya, Todorowski, and Ruggiero win those roles hands down. Since in Tharp’s mind, hell is probably a dance she couldn’t pull off, she undoubtedly achieved heaven with this one.

Thanks Deborah. An illuminating review of a show that I in fact have already reviewed in Portland. I’m glad to know what I missed, which is quite a lot in Preludes and Fugues due to lousy sight lines in the venue.