Sylvie Guillem dances into retirement.

Force of Nature. That’s the title of a documentary about the career of the formidable French dancer, Sylvie Guillem (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QmMaNQBED8Q). You can see her at 19, when she was promoted to the rank of étoile in the Paris Opera Ballet by its then director Rudolf Nureyev. She is startling as a ballerina. Although her long neck, proud little head, slim body, long legs, and beautifully arched feet are not uncommon, her flexibility is. Guillem began her career as a gymnast, and discovered ballet almost by accident.

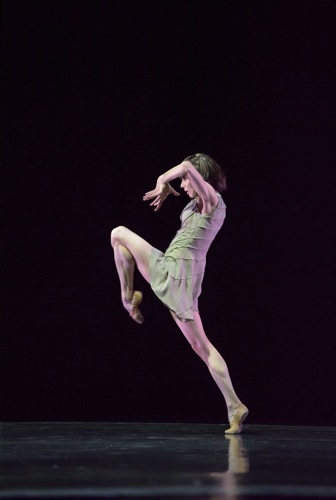

That early training shows. Watching her in some early films and seeing her at 50, performing onstage at City Center in her Sylvie Guillem: Life in Progress, you could believe that her hips are engineered differently from those of other dancers. She may lift a leg to the side with no apparent effort; it floats up and, just when you’d expect it to arrive at a reasonable height, she slips it into overdrive, and there it is, past high noon. When she leaps sideways, her legs split almost as soon as she takes off. The effect is both thrilling and slightly vulgar, but her cool presentation (or dramatic involvement, depending on the dance) downplays both.

For most of her career—at the Paris Opera, in Britain’s Royal Ballet, and as a guest artist with other companies—Guillem has chosen her roles carefully. And over the years, she has embarked on projects as diverse as staging a new version of Giselle for the Finnish National Ballet and the Ballet of La Scala and performing two solos from the 1920s by Germany’s pioneer of modern dance, Mary Wigman. Like Wendy Whelan, who began to work with choreographers in contemporary dance as she withdrew from her roles as a principal dancer with New York City Ballet, Guillem has commissioned for her current program works by four highly individual European dancemakers: Akram Khan, William Forsythe, Russell Maliphant, and Mats Ek—all of whom require flexibility of both mind and body. She wants, she says, to be “émerveillé” by the work she undertakes—amazed, made to marvel. The choreographers of the three dances featuring her were clearly émerveillés by her; wanting both to honor her and to challenge her gently, none produced a masterpiece. Perhaps that was to be expected.

Sylvie Guillem: Life in Progress constitutes her farewell tour. On December 30, 2015, in Japan, she will perform for the last time. If you insist on seeing her as a ballerina, go online; she will not venture into that world again. In fact, Khan’s Technê begins by making us unsure whether she is even human. Alies Sluiter’s score begins tremulously with light rattling sounds, birds, growing thunder, a developing melody, but remains mysterious, even as it becomes more forcefully rhythmic. The musicians and co-composers sit at the back: percussionist Prathap Ramachandra, Grace Savage beatboxing, and Sluiter playing violin, viola, and laptop. A leafless tree made of silver wire gleams in the dim lighting by Adam Carrée and Lucy Carter.

Guillem—wearing a stylish, skimpy costume by Kimie Nakano— enters on all fours. She creeps along in a squat and operates from that position for a surprisingly long time. She’s wearing a wig of chopped-off dark hair that hides her face much of the time. You become hyper-aware of her elbows and knees—how bent they are, how pointed. She could be a grasshopper. She travels rapidly across the front of the stage, still in a squat (no hands) and bouréeing, her feet fairly twinkling. She actually spins on one toe in that position to end in a deep lunge.

The title, Technê, is from the Greek, a program note explains, and means “knowledge based in practice: the human ability to make and perform.” Perhaps the tree is the Tree of Knowledge. Guillem touches it once and makes incantatory gestures toward it with her hands, flutters her mobile fingers, and, behold, the tree slowly begins to rotate. I’m not sure this empowers her; in the end she’s again walking in a squat. Humbled? Reduced? Not sure.

Guillem dances in only three of the four dances programmed. Two men, Brigel Gjoka and Riley Watts, both of whom were associated with The Forsythe Company before it closed, perform Forsythe’s Duo2015, a new version of the choreographer’s 1996 Duo. I read the program note after the event, and it makes my head ache. Did I really see “a clock composed of two dancers?” Was I able to understand that I was watching dancers “register time in a spiraling way, make it visible, thinking about how it fits into the space?” Readers, I fell down on the job.

What I did observe was two extremely interesting, quite endearing men moving primarily in a small area of space at the front and center of the stage, pinned there by Tanja Rühl’s lighting. Whatever the process by which the dance was constructed, the result is a particular kind of rhythm—the kind we associate with an intricate task that requires two people. This isn’t heavy lifting; it means trying to make moves that fit together; one dancer may start something that the other responds to. They watch each other carefully, and occasionally stare at something above their heads. Watts often slides his eyes sideways, as if he needs to be aware of something beyond the space the two inhabit.

Sometimes Willems’s score falls silent; sometimes it accosts the men. They are expert Forsythians, able to set parts of the body in silky contention with one another. Their spines are super-flexible, eel-like. Watts is a contortionist as well, and the choreography makes use of his ball-bearing joints. The dancers’ very strangeness elicits laughter and the occasional gasp. If you saw them moving like this on the street, you’d want to give them a wide berth. But they carry on, their demanding collaborative job, which is not without humor or contentiousness. Duo seems long at times; you keep expecting to end, but it re-energizes itself and forges ahead.

Maliphant’s Here and After also begins by pinning two dancers in a small, downstage space area. This time, they are women—Guillem and Emanuela Montanari. Michael Hull’s lighting patterns their pale orange outfits (by Stevie Stewart) with irregular rust-colored stripes. Andy Cowton’s music creates an enigmatic atmosphere that begins sparsely, with electronic crickets and a single sustained tone; low rumbles, the sound of breathing, heavy beats, a muffled voice, and yodels work their way in. (Re the yodeling and the title: Guillem has a home in the Alps.)

The women bring to mind Siamese twins, even though they’re not joined at the hip. Their mission seems to be to create pleasing designs together, to hold hands, to lean apart and counter-balance each other. When they separate, it’s to retreat to the back of the stage, come forward, retreat again, etc. Playfulness enters the picture as the dance expands to affirm friendship and collegiality.

Of all the program notes that the choreographers have contributed, I prefer the one that Ek has affixed to his 2011 Bye: “A woman enters a room. After a while she is ready to leave it. Ready to join others.” That pretty much sums up the solo—the most complex work on the program— leaving you free to discover for yourself the resonances that vibrate together in it. The music that accompanies Bye, the second half (Arietta) of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, Op. 111, gives the dance gravitas. Since Guillem is retiring from dance; what better accompaniment than the great composer’s last sonata for piano? The music, however, eventually turns frisky, its syncopations imparting an air of embryonic jazz.

Elias Benxon’s intermittent film images confirm the stage as an artistic playground that Guillem is preparing to leave. In an opening in the rear curtains, stands a doorframe within which a life-sized, black-and-white image of Guillem stands contemplating the stage, a bit hesitant about entering. Suddenly, her flesh-and-blood hands appear over the top of the frame she’s attempting to climb. At various times in the dance, she will step into the frame’s side, her reaching leg becoming monochromatic before it pulls the rest of her temporarily into grayness.

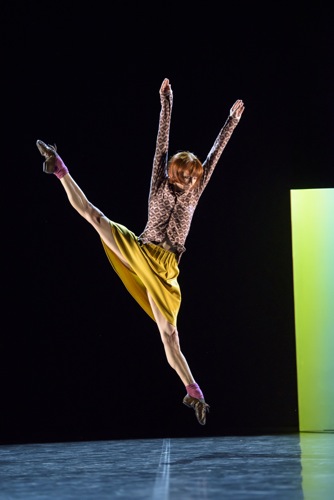

Perhaps to counter the colorlessness that represents a world not yet fully inhabited, costume designer Katrin Brännström has dressed Guillem in vivid colors: a bright yellow skirt, purple socks, a patterned brown shirts, a green sweater. Her red hair, short in front and tied into a ponytail at the back, adds to the effect. Still, she looks like an orphan in the theatrical space lit by Erik Berglund.

Over the course of Bye, Guillem refers to a dancer’s daily practice, as well as (perhaps) to stages in her career. She takes off the sweater, removes her shoes and socks, and wiggles toes that appear as flexible as all her other joints. She gives us more visions of those startling, almost prehensile legs, those feet a young ballet student would die for. She leaps, she romps around her world; she knocks on invisible doors.

The end involves more trickery, some of it puzzling—such her silent scream, followed by an overhead shot of her onstage sprawled on a green mat (or screen), which is transported to the space beyond the door. More powerful is the preceding black-and-white film image of a man looking around searchingly; not seeing Guillem’s three-dimensional self on the stage, he walks away. Soon he returns, and others join him—adults and children. She slips through the portal, and as the virtual group walks away from the stage, she becomes a member of it. In that parallel world, you can hardly find Sylvie Guillem the ballerina. And that’s how she wants it.

The silent scream has become the cliche to end all cliches (sorry, can’t do diatonics in this format) and I don’t regret not seeing yet another one. Instead, I will cling to the memory of Guillem in a Royal Ballet performance of “In the middle somewhat elevated” and wish her merde and godspeed at whatever she wants to do next. Thanks Deborah for the customary vivid writing.

Beautiful writing as always. The long clip of Sylvie really helped to appreciate this dancer’s life, and though I’ll never get to see Sylvie, with your writing I feel enhanced by her part of dance.

For about 20 years I spent half the year in my NYC apartment and getting to see lots of dance. Often I got to see some of the performances you covered, and always enjoyed reading your take on them. Very often your keen eye and pen presented aspects I did not fully understand or appreciate, and wanted to experience again as if with your guidance.

Sadly we had to sell our NYC apartment, and now spend almost all year in Boise, Idaho. And though Trey McIntyre has left, we have some dance groups getting stronger and better and I sometimes imagine what you might have observed in their efforts. I’m sure you would be generous and supportive, even though you are so used to the finest dance performances so routinely.

Greetings Deborah,

Once again you have allowed me, with your writing, to feel as though I sat with you seeing Sylvie Guillem perform.

When I first saw her as a young dancer she seemed like a cartoon with every part of her, those hyperextended legs, super high extensions and astonishing feet so exaggerated and seemingly asking to be exploited if in the wrong hands ( and I can think of a few of those).

Over the years my admiration of her has grown as I have seen her develop as an artist and, especially, avoid my expected exploitation of her physical gifts.

Brava to not only a fine artist but an intelligent, honest woman.