New York City Ballet presents its 2015 fall gala, “From the Runway to the Stage.”

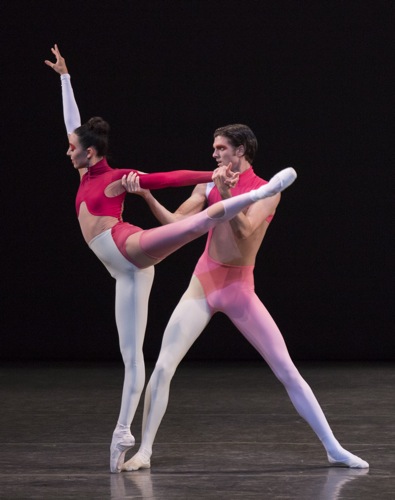

Georgina Pazcoguin Georgina Pazcoguin and Meagan Mann in Justin Peck’s New Blood. Photo: Paul Kolnik

For the fourth year in a row, the New York City Ballet has devoted its fall gala to fashion, a custom started by the vice-chairman of the NYCB board, Sarah Jessica Parker. Pairing celebrated couturiers with choreographers is a scheme that lures audiences with money to spend, as well as gowns to wear to the gala that compete with the onstage costumes. This year’s gala raised close to 2.7 million dollars, which may not seem like a princely sum to today’s billionaires, but it contributes considerably to keeping a dance company on its feet, so to speak.

Moving through the crowded Promenade before the performance was itself a ballet. Quite a few women wore slim-cut ball gowns with trains and swam through the mob like mermaids, sure that the currents they stirred up would keep the rest of us stepping carefully as we slipped through the knots of chatting people. One friend and colleague stepped on a passing wake of fabric, was thrown forward, yet managed to stay upright (although she spilled her champagne on another woman’s shimmering dress). Witnesses applauded her grace, she reported.

As usual, a short film preceded the evening. Designers talking, dancers draped in fabric, choreographers scrutinizing the result, and through it all costume supervisor Marc Happel and his assistants trying to make everything work— that is, making sure the dancers could move. At one stage in the process, cast members of Troy Schumacher’s new ballet kept their faces calm while trying on outfits designed by Marta Marques and Paulo Almeida of Marques’Almeida; it was Happel who pointed out that long strings trailing off the costumes and along the floor really would not work.

This year’s gala featured premieres by four choreographers (all men, but I won’t carry on about that here): Myles Thatcher, Robert Binet, Justin Peck, and Schumacher. A revival of Peter Martins’s 2003 Thou Swell got new costumes too. I found Thatcher’s Polaris and Peck’s New Blood to be the most compelling of the new ballets, but all four are polished, fairly adventurous, and show off their dancers in becoming ways. The choreographers worked with small, unevenly numbered casts, downplayed or avoided traditional gender pairing, and preferred asymmetrical patterns. All of which is refreshing.

Myles Thatcher’s Polaris. (L to R): Ghaleb Kayali, Emilie Gerrity, Craig Hall, Ashly Isaacs, Andrew Scordato (hidden), Daniel Applebaum, and Taylor Stanley.

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Zuhair Murad designed the simple, becoming costumes for Polaris (he also provided Sarah Jessica Parker’s silvery party dress). Four of the ballet’s five men wear tights and vests in shades of blue, while two of its three women (Emilie Gerrity and Ashley Isaacs) are clad in knee-length, sleeveless, pale blue dresses with subtle lacy patterns and tiny sparkles strewn here and there. Tiler Peck’s dress is paler still, and Craig Hall, her sometime partner, wears white.

Thatcher, a dancer in the San Francisco Ballet’s corps, has choreographed for the SFB and the Joffrey Ballet. Last year, he was mentored by Alexei Ratmansky in the Rolex Mentor and Protegée Arts Initiative; it’s clear that he learned a lot.

Polaris, set to the Allegramente from William Walton’s Piano Quartet in D Minor, suggests in its patterns the North Star at the tip of the Little Dipper’s handle, around which the other constellations appear to move. In human terms, Peck is both part of the group and separated from it. She often stands alone, staring into distant space, or watching her colleagues dance or run past her. Thatcher makes the space alive and keeps our eyes busy. In one wonderful passage, Hall, the two other women, Daniel Applebaum. Ghaleb Kayali, Andrew Scordato, and Taylor Stanley form a chain, each laying a hand on the shoulder of the person in front of him or her. Within that chain they move, changing places, creating a flow, and as they do so, the last man reaches out a scoops Peck into the chain. When they swirl into another more complex formation, she’s at its heart, but after a few seconds, she ducks out of it and, while they freeze, dances around them with a beautiful air of discovery, then resumes her place in the group, which instantly spurts apart into new patterns.

Robert Binet is a choreographic associate in the National Ballet Ballet of Canada and has created works for several other companies. If he had a mentor, it was John Neumeier (Binet choreographed a full-evening work for the second company of the Hamburg Ballet, where Neumeier is artistic director and chief choreographer). The Blue of Distance is set to two lovely, impressionistic Ravel piano pieces (finely played by Elaine Chelton)— the first, Oiseaux Tristes, with its deep, somber chords and high, fitful flutterings evoking the birds of its title, and Une Barque sur l’Océan, which ripples and rocks its way in and out of turbulence. In speaking of her costume designs, Hanako Maeda of ADEAM, related the men’s royal blue unitards and the women’s strange blue fish-scale bodices and foamy skirts to water.

The Blue of Distance is performed by Sterling Hyltin, Rebecca Krohn, Sara Mearns, Tyler Angle, Harrison Ball, Preston Chamblee, and Gonzalo Garcia; six of them at times form pairs. A duet for Mearns and Angle to Oiseaux Tristes is dreamy, and her marvelous arms flutter like wings. There are some fine moments and a pervading sense of yearning, of reaching (especially from Mearns and from Ball), but I can’t find the ballet’s center—the force that holds it together.

New York City Ballet dancers in Troy Schumacher’s Common Ground ((L to R): Anthony Huxley, Alexa Maxwell, Teresa Reichlen, Joseph Gordon, and Russell Janzen. Photo: Paul Kolnik

Any center to Schumacher’s Common Ground is stated most strongly by Ellis Luwig-Leon’s excellent commissioned score and playfully sabotaged by Marques and Almeida’s vivid, distracting costumes. Is that bundle of flying red fabric Amar Ramasar? Wait till he slows down and I’ll tell you. Will that floating blue panel on Teresa Reichlen’s mostly green and blue whatsit wrap around her knees and hamper her? Streamers are attached to people’s wrists, adding to the complications. The costumes are constructed of irregularly shaped, lightweight, bright-colored fabric, and each one may be a work of art. The dancers look like brightly colored birds. Sometimes they’re wild; sometimes they travel as a flock; sometimes they move in slow motion.

Schumacher is a member of NYCB’s corps de ballet and a talented choreographer. I greatly admired his Clearing Dawn, a highlight of the 2014 fall gala. And the fact that he knows these dancers well shows in his work. But I lost my way through Common Ground. Odd, often intriguing things happen. Tall Reichlen dances with slightly shorter Huxley (such a fine dancer). Then Joseph Gordon carries Huxley away. All seven dancers circle and feel the floor. The last image is enigmatic. One by one, most of them lie down on their backs side by side, like sardines waiting to be packed closer together. The curtain descends. The other intrepid performers are Ashley Laracey, Alexa Maxwell, and Russell Janzen.

I should have mentioned before now that it’s always a pleasure to see members of NYCB’s corps de ballet presented on equal footing with principal dancers and soloists. The title of Justin Peck’s ballet, New Blood, could indirectly allude to that. Its cast consists of three principal dancers, five soloists, and six members of the corps. But New Blood also refers to the ballet’s bold structure, and that structure is determined in part by the music that accompanies it: Steve Reich’s Variations for Vibes, Piano and Strings. The music critic Alex Ross wrote in 2006 of it and two other works by the composer “Reich has consolidated four decades of invention. Neon-lit textures have given way to dense, dusky landscapes, with tender lyrical passages at the heart of each piece.” But, of course, because Reich is Reich, there’s a constant rapid pulse underneath the irregular bass syncopations of the pianos and the high outcries of the strings and vibes.

This glorious three-movement piece of music for two pianos, four vibraphones, and three string quartets was meant to be danced to; it was commissioned in 2005 for British choreographer Akram Kahn and the London Sinfonietta. Peck’s sensitivity to the score has given birth to a ballet in which the music is less a landscape to be inhabited than a sleek mechanism that drives the dancing along. It begins with the dancers in a line stretching from the front of the stage to the back; From there, they break out, re-build, split into two lines. Amid the arresting patterns of this first group section is a moment in which women lie supine, and the men kneeling beside them press repeatedly down on their partners’chests, as if trying to re-start their hearts.

But what Peck heard in the music also influenced him to start a dance game of never-stopping variations. So Peter Walker dances with Brittany Pollack; as he leaves, Taylor Stanley replaces him as Pollack’s partner. When Pollack’s ready to go, David Prottas is standing by to join Stanley. Inevitably, as the duet material cycles through its changes, women dance with women, men with men, men with women. When I think back on it, I envision the dancers staying side by side in many of these fleeting, strikingly clear duets. Although I didn’t think to count the partner-changes, there could have been as many as eleven before the final couple, Ashley Bouder and Adrian Danchig-Waring, takes over the stage.

The costumes for New Blood were designed by Humberto Leon of Opening Ceremony and Kenzo. The dancers wear trim unitards, but within that basic structure, patches of a particular hue vie with skin-colored fabric or shade from the main color to white.

Peter Martins’s Thou Swell. (L to R): Amar Ramasar, Ask la Cour, and Robert Fairchild admire Rebecca Krohn. Photo: Paul Kolnik

The four principal women in the revival of Martins’sThou Swell, however, have worn their most soignée evening gowns (by Peter Copping of Oscar de la Renta) to Robin Wagner’s nightclub setting. They stand out like butterflies next to their all-in-black swains. Their gowns are slightly off-key with the music; all but two of the songs by Richard Rodgers (in disappointing arrangements by Don Sebesky) date from the 1920s and 1930s. Mearns’s full, filmy, pale blue outfit could belong to almost any 20th-century girl ready for the senior prom, while Sterling Hyltin wears a peculiar short, fringy shift in emerald green. The elegant, intricately cut (and cut-out) gowns worn by Reichlen and Krohn move beautifully, but, because both are split up one side to allow the women’s bare left legs to whip out, the glimpses of crotches that they offer would surely have earned the disapproval of a maître d’hotel of those decades.

The women enter with cloaks, and Hyltin and Krohn also sport boas of a sort—so compact and puffy that their heads seem to be emerging from bushes. And then. . .well you know, Martins skillfully limns romantic or frisky or flirty encounters between these gorgeous women and their partners (or the partners of others): Robert Fairchild (taking a night’s leave from his role in the Broadway production of American in Paris), Ramasar, Jared Angle, and Ask la Cour. In contrast to the rest of the evening’s asymmetries, Thou Swell’s mirrored, two-level club maintains a staff of four pert, tutued waitresses and four waiters to hustle around and spell the clientele in dancing.

The club not only has an orchestra (the one hidden in the pit) plus white-coated onstage NYCB musicians: Alan Moverman (piano) Ron Wasserman (bass), and James Saporito (drums). Two fine singers, Norm Louis and Rebecca Luker deliver some of Rodgers and Hart’s familiar sweet songs about love.

Andrews Sill conducted the NYCB orchestra when the evening called for one, and Mark Stanley lit all five ballets with his customary subtlety and finesse.

Then when the dancing was done, some of those who’d been onstage put on their party clothes (super-glamorous, judging from what I glimpsed), went to the gala dinner, and probably danced the night away. Four new ballets and a chunk of money for the company they grace—not a bad night’s haul.

Astute, and sharp. I appreciate the restraint and the difficulty it implies.

K

Agree totally with Ms. Kaschock, although lord knows the costumes have overwhelmed the choreography in City Ballet’s past, e.g. Kurt Seligmann’s costumes for Balanchine’s “Four Temperaments” in 1946, not that Seligmann was a couturier of any kind. Egos, egos everywhere!

I always enjoy seeing new work—or reading about it, as in this case—but I can’t help thinking, just from glancing at the pictures, that this emphasis on costuming for the NYCB gala programs is becoming distracting. That was true the last time I attended, a couple of years ago: I saw quite enough fancy costuming on the plaza and in the lobby beforehand and would’ve welcomed an entire program in rehearsal clothes. And bringing the rag trade into the dance scene could lead either to valuable cross-pollination or, less good, to bruised egos and production headaches. Apparently NYCB believes it’s paying off. I sure hope so.

Thought-provoking and beautifully written – as always. Thank you Ms. Jowitt – your view and observations helped me feel I was in the very theatre, instead of hundreds of miles away!

Brilliant, Ms Jowitt – with thanks from many of us (in other states and nations) who read your articles while we cannot reach the actual performances in NYC..

Ms. Jowitt,

Could I correct one small semantic detail? Robert Binet is a Choreographic Associate with the National Ballet of Canada, not Canada’s Royal Ballet.

Canada has a ‘royal’ company (the Royal Winnipeg Ballet), but the National Ballet is proud of our association with Robert and would regret the confusion.

yours,

Jeff Morrris

Yikes! Thanks to Jeff Morris for reminding me that my fingers sometimes have minds of their own. The correction will be made instantly.