American Ballet Theatre opens it Lincoln Center season with ballets by Morris, Ashton, and Tharp

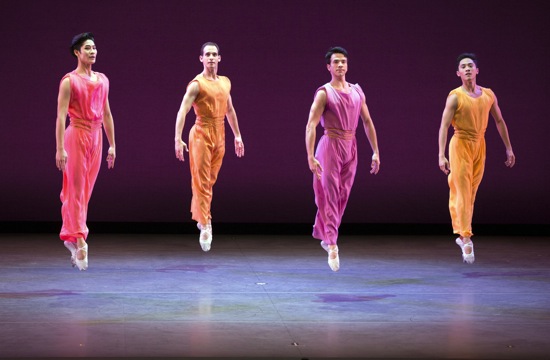

Mark Morris’s After You. (L to R): Joo Won Ahn, Craig Salstein, Arron Scott and Jeffrey Cirio. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Ask a choreographer bred in modern dance to create a ballet for an esteemed classical company, and what ensues? If the choreographer in question is Mark Morris or Twyla Tharp, the resultant work often both honors tradition and knocks it around a little. This seemed true at American Ballet Theatre’s first-night gala, which opened the company’s two-week Lincoln Center season with the New York premiere of Morris’s After You and ended with a revival of Tharp’s The Brahms-Haydn Variations (2000). Even Frederick Ashton, whose peerless1966 Monotones I and II was sandwiched between those two ballets, had moments of pushing the classical vocabulary out of its 19th-century confines.

Morris’s charming ballet is set to Johan Nepomuk Hummel’s Septet in C Major, No. 2, Opus 114. The music is as egalitarian as the dancing. The trumpet that must have given the septet its sobriquet of “military” conducts a little affair with the piano as the opening Allegro con Brio begins; flute, clarinet, violin, cello, and double bass have periodic rises into conversational prominence. The twelve dancers are listed in alphabetical order; Isaac Mizrahi’s masterfully cut sleeveless jumpsuits make no distinctions in color or cut among principals, soloists, and members corps de ballet, or between men and women. And Morris, as is his wont, subverts both hierarchy and gender behavior. Men and women dance as partners, but men also dance with each other, and occasionally a woman lifts a man.

The title After You could be stretched a bit to include the composer’s history. When he was born in a tiny yellow house (now a museum) in 1778, the surrounding city was Pressburg, Hungary (part of the Austrian Hapsburg Monarchy); it subsequently became Bratislava, Slovakia. As an eight-year-old, he was studying with Mozart in Vienna; when he was 13 and in London, Haydn composed a sonata for him. In 1792, back in Vienna, he studied with Haydn, as did a talented 20-year-old composer, Beethoven. Hummel later made arrangements of works by all three of them. After you Wolfgang, Josef, Ludwig.

The title of Morris’s ballet becomes evident in terms of dancerly behavior. Very near the beginning, Stella Abrera is dancing with Calvin Royal III and Arron Scott (“now you take her; no, it’s your turn”); the men go off together, and Abrera makes a gracious gesture toward the wings that ushers in a line of six dancers, three of whom immediately escort her away, leaving the stage clear for Craig Salstein, Devon Teuscher, and Catherine Hurlin. Others are equally hospitable—even Gillian Murphy, who seems, for a few seconds, surprised to find herself alone.

After You is a sunny-afternoon ballet; a slight breeze blows through it. The dancers perform easily and buoyantly—accurately, of course (and the women are on pointe), but not making a big deal of it. If I could run up and join them, I’d like that. The phrases are not crammed with steps, and that contributes to the work’s free-flowing air. An absence of effortful preparation makes the variety of leaps and hops resemble flying. This is not to say the movement isn’t difficult; Murphy masters a solo in the Adagio section that has her moving slowly and fluidly from one feat of balance act to another, perhaps testing the air.

The comings-and-goings that Morris has devised (some of them fleeting) wittily suggest the collegiality and separations that happen at parties. Royal makes a solo foray into big turning leaps in a circle and finishes by rolling on the floor. Four men hurry in to spell him in the same activity (perhaps because of something Morris heard in the music, but conveying a “let’s do that too” sportiveness). At the end of the first section, there’s a quiet moment; then the trumpet sounds, and Jeffrey Cirio, who’s closest to the wings, lifts every other person lined up onstage and deposits him/her closer to the exit; he’s a living turnstile.

Since the choreography presents the dancers as equals, here are the names of those I haven’t mentioned: Sterling Baca, Skylar Brandt, and Lily Wisdom (replacing Gemma Bond). In Morris’s own company, his performers often appear as individuals; that’s how (assisted by Tina Fehlandt) he has presented the dozen ABT dancers who inhabit After You.

Morris doesn’t use Hummel’s fourth movement. The ballet ends with Septet’s Menuetto. But, strangely, it doesn’t really END. Nor are the dancers clearly going to keep dancing until the lights go out. Perhaps a cue in Michael Chybowski’s excellent lighting went wrong at the gala, but a few dancers were scrimmaging around at the left side of the stage as the lights quickly dimmed to black. Too busy saying “after you” to say goodnight?

In 1976, Twyla Tharp’s remarkable Push Comes to Shove, her first work for ABT, she showed off the dauntless Mikhail Baryshnikov. This was just two years after he defected from Russia and the then-named Kirov Ballet. The solo she created for him early in Push is a masterpiece of loving subversion of all that he could accomplish; carefully preparing himself for a pirouette, for instance, he might then spin in the opposite direction of the one predicted. I’m thinking especially, however, of the second movement’s big ensemble section, in which, from time to time, various women in the symmetrically spaced and divided corps de ballet kept leaving the ranks and defecting to the opposite group.

The Brahms-Haydn Variations (set to Johannes Brahms’s “Variations on a Theme by Haydn for Orchestra, Op. 56a”) is less irreverent. Choreographed almost 25 years after Push Comes to Shove, this ballet shows Tharp more at home with the classical tradition and a bit less scampy. (Susan Jones, the former ABT dancer who assisted Tharp on Push Comes to Shove, has staged it excellently, but with perhaps a shade too much starch.)

I confess to loving The Brahms-Haydn Variations less than I do Tharp’s magnificent In the Upper Room, created for her own company in 1986 to a commissioned score by Philip Glass and set on ABT dancers in 1988. She attacked all the permutations of Brahms’ triumphant theme with her usual zest for countering tradition with innovation, but the ballet moves along like a grande dame who, despite losing an earring or stepping on her own train occasionally, will maintain her decorum somehow.

Take the corps de ballet: eight men and eight women dressed in white (costumes by Santo Loquasto). A bunch of them may dance in unison; every man may lift his woman. But they don’t stay put. Mannerly and gracious, they may form ranks asymmetrically, split in two, or disappear soon after arriving, as if they’re needed elsewhere. Sometime the women ditch the men. If a wedding-cake formation is required to climax a variation, they’re ready to come be part of it.

On the other hand, these folks are fickle. When Gillian Murphy and James Whiteside walk in and start dancing in the spot just vacated by Danil Simpkin and Sarah Lane, the others onstage (that includes new arrivals Christine Shevchenko and Joseph Gorak) can’t decide whether they want to stay and participate, or take a break and return. Murphy and Whiteside are still dancing imperturbably and very beautifully, when some and/or others reappear. It’s a challenge to keep track of the five principal pairs (these include Isabella Boyleston and Sterling Baca) amid the free-spirited corps dancers. Also prominent are Maria Kochetkova and Herman Cornejo (he’s the only one of the original cast members still on hand, and maybe he’s in a different role). To this couple’s gentle variation, he brings a touch of sweet jazziness and a bit of a caper, before scooping her up in a cuddlesome lift and carrying her away.

The five pairs mentioned wear brown costumes (quite casual for the men), while the two pairs of demi-soloists (Cassandra Trenary and Blaine Hoven, Luciana Paris and Roman Zhurbin) are dressed in a shade between cream and beige. As an example of the compositional mischief, Hoven, out of nowhere, embarks on a bold solo, but very soon he’s hidden behind various entering guests at this lavish party. What was on his mind? We’ll never know.

Certainly the ballet is a grand one, rich in demanding, great-looking dancing. In that richness, it matches Brahms’s music (conducted by Charles Barker). If you’ll forgive another analogy, the ballet makes me think of a fancy fruitcake. Did more dried cherries end up in one slice than in another? Oh look, I got two pieces of pecan. Except that, of course, we’re not talking about delicious tidbits but about superb dancers, mixed by a master. I hope they’ll have a little more fun with The Brahms-Haydn Variations as they warm to it.

Frederick Ashton’s Monotones I. (L to R): Isabella Boyleston, Joseph Gorak, and Stella Abrera. Photo: Marty Sohl

Between Morris’s work and Tharp’s, Ashton’s Monotones create a quiet dream of symbiosis, taking place in the wistful sonorities of Erik Satie’s Trois Gnossiennes and his Trois Gymnopédies (although the orchestrations of the latter—conducted by Ormsby Wilkins—sounded strangely loud).

Ashton conceived the three dancers of the first as triplets, or a split-image of one dancer. In their pale greenish yellow, long-sleeved, belted unitards and helmet-like caps, the man and two women of Monotones I resemble Picasso’s saltimbanques They move almost always in exact unison and very close together. Nothing they do is extreme, their every move is precise. Stepping out together into arabesque, they lift their legs to exactly the same height—neither too high nor too low. In perfect synchrony, they begin their dance with one arm held up, as if they need to shade their eyes from a too-bright sun. Neither happy nor sad, gracious to one another, they seem unable to imagine being apart for more than a few seconds. ABT’s Abrera, Boylston, and Gorak perform the trio with lovely self-absorption. (The audience realizes, I think, how extremely difficult the dancers’ long, calm balances on one leg can be and applauds them enthusiastically when the trio is over.)

Only at the end of Monotones I do I sense a conflict between these classically pure creatures that Ashton created and what he gave them to do. Just at the end, the two women, standing on either side of the man, dip forward into arabesque penché, each lifting her leg high enough to rest it on one of his shoulders. For a minute, he, holding each by the hand, looks as if he’s wearing an uncomfortable garment.

Frederick Ashton’s Monotones II. (L to R): Cory Stearns, Veronika Part, and Thomas Forster. Photo: Marty Sohl

I have similarly heretical thoughts watching Monotones II; this amounts to a suddenly perceived tension between Ashton’s delicately sculptural presentation of three beautiful studious beings—statues come to life perhaps— and what you’d think if you saw three dancers doing what they do but in a dramatic ballet.

These three—wonderfully danced by Veronika Part, Thomas Forster, and Cory Stearns—are dressed like the three in Monotones I, and their belts and caps, like those of the other three, glint discreetly here and there. For me, the image of the woman is rife with conflict. At the outset, Ashton, like Morris and Tharp, pulls the classical tradition into contemporaneity. When the light go up on the scene (moonlight to Monotones I’s sunlight), Part is in a split on the floor, her head bent over to touch the knee of her front leg, her hands clasped around her ankle. The two men bend forward and slowly tilt her backward until she’s standing on one pointe holding her other leg in front of her face. She might well be a doll; someone else has to move her limbs, or turn her however you like, she’ll be in the same pose.

For a while, Forster and Stearns keep Part between them, gravely and slowly manipulating her in uncanny ways—holding one of her legs high and then collaborating on turning her under it and around into an arabesque. Only now does she seem to acquire a degree of agency, looking lovely and rather proud, instead of like a human turnstile or a docile acrobat letting her team work out a faintly risqué new act.

For the rest of this fascinating trio, she behaves graciously toward the men—sometimes moving in close, comradely unison with them, sometimes allowing one of them to lift her or rotate her. Each of the three knows his/her place in what now seems to be a harmonious relationship (no hint of a ménage à trois). When one of the woman’s partners carries her along, the other spins a few pirouettes and waits his turn.

Ashton created Monotones II in 1965, but put the 1966 trio first when he joined them. Still, thinking of their order of creation, I had the irreverent thought that perhaps, floating around in Ashton’s head, was the notion of a goddess who had become pregnant by two best-friend gods (surely a common occurrence in Greek myth) and spawned divine triplets.

ABT’s fall season continues through October 31 and includes Kurt Jooss’s great 1933 The Green Table, Paul Taylor’s Company B, and principal dancer Marcelo Gomes’s AfterEffect featuring James Whiteside and Misty Copeland.

Thanks so much for giving those of us who couldn’t be there, a sense of the new Morris! I so wish I could have seen it. I also loved the fruit-cake analogy for Tharp. I’ve noticed that quality in her work in general and although it may be a response to Brahms own musical density (there sure is a lot going on!) it seems to me that she loves to “pack in” movements — kind of like those medieval tapestries in which every tiny space if filled with flowers, foliage, animals, etc.etc. It is all interesting and it all fits together to a make a unified whole — but it is hard to take it all in. There is a kind of driven quality — she’s intense as well as dense– you want a little more breathing room, but it can be thrilling too.

.