Fall for Dance returns to New York City Center for the eleventh time.

Dorrance Dance in Michelle Dorrance’s Myelination: (L to R): Leonardo Sandoval, Megan Bartula, Christopher Broughton, Michelle Dorrance, Elizabeth Burke, Claudia Rahardjanoto, Warren Craft. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Every autumn, as the leaves change color and begin to consider falling, Fall for Dance defines the verb differently: New Yorkers and savvy visitors buy bargain-price tickets and fall in love with dance—or at least with some of the twenty companies, small ensembles, pairs, and soloists who fill five mixed-bill programs at City Center.

This year, dance fans and newcomers could see something as lushly athletic as Paul Taylor’s Brandenburgs and as possibly unfamiliar as Nrityagram’s performance in India’s Odissi style. They could thrill to the unlikely pairings of American Ballet Theatre’s Herman Cornejo and Fang-Yi Sheu, a former member of the Martha Graham Dance Company, in a duet by Sheu; or NYCB principal dancer Tiler Peck performing with Bill Irwin (both these venturesome duets co-commissioned by Fall for Dance and the Vail International Dance Festival). A new piece by Doug Elkins! Boston Ballet performing a Pas de Quatre by the almost forgotten 20th-century Russian choreographer Leonid Jacobson!

What has often struck me about this annual horn-of-plenty season is how adroitly the dances are chosen and programmed. The one evening I was able to attend offered the New York premiere of Nrityagram’s Shivashtakam, a performance of Hans van Manen’s Solo by three principals of the San Francisco Ballet, Stephen Petronio’s Locomotor, and the world premiere of Michelle Dorrance’s Myelination.

Shivashtakam (An Ode to Shiva): Bijayini Satpathy (standing) and Surupa Sen of Nritygram. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Shivashtakam was inspired by the 9th-century poet Adi Shankaracharya’s verses about the Hindu god Shiva as both creator and destroyer. Since Odissi is traditionally a solo form, a single dancer usually embodies him in those aspects, as well as conveying the gods and demons in his orbit and the metaphors that liken him to other creatures and elements. She also portrays herself as a devotee. Nrityagram’s artistic director, the superb dancer Bijayini Satpathy, begins by flashing for our edification the relevant gestures and facial expressions, while an unseen voice recounts the words.

But while the dancing that ensues is traditional (the deep kneebends, wide stances, sinuous arms, hands that flick out fleeting visions of serpents or unloosing an arrow from a bow, eyes that widen into ferocity or soften amorously), the women of Nrityagram present their own structural innovations. The musicians playing Pandit Raghunath Panigrahi’s composition (for bamboo flute, drum, violin, harmonium, and vocals) usher in Surupa Sen, who is also the choreographer for Shivashtakam. Sometimes she and Satpathy perform exacting rhythmic footwork in unison, but they also separate into counterpoint. Often, one waits in a pose while the other performs. Shiva’s attributes and accomplishments remain paramount, but embodiment becomes wonderfully slippery and multi-faceted, as open to transformations as the Hindu gods and goddesses themselves.

Three sterling men of the San Francisco Ballet demonstrate another kind of transformation in van Manen’s 1997 Solo. It’s inevitable that Hansuke Yamamoto, Joseph Walsh, and Gennadi Nedvigin would eventually begin to overlap their onstage activities and eventually perform in unison. However, the pleasure of the work is watching the men succeed one another in what is, for the most part, one long solo set to the “Courante” and “Double” from J.S. Bach’s devilish Violin Partita No. 1 in B Minor. The choreography, tailored to three individuals, is as virtuosic as the music, but although it draws on ballet, it avoids rules and conventions (I only counted one pirouette that began with a planted preparation).

The men perform with a kind of ease, as if they’d slipped under the skin of the movement. Aside from indulging in van Manen’s occasional jokey moment, they approach the often inventive and very attractive choreography as if it were a pleasant, if demanding task that they’ve embarked on. No big deal, they seem to be saying as they loft and twist fluidly into movements that could qualify as very big deals indeed.

Stephen Petronio’s Locomotor: (L to R) Jaqlin Medlock, Gino Grenek, Joshua Tuason, and Emily Stone. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Van Manen’s trio could be seen as warming us up for Petronio’s 2014 Locomotor, which opens with an uncanny performance by special guest Melissa Toogood. This is a solo that deserves to be called a soliloquy. As is often the case in a piece by Petronio, the dancer’s arms, legs, body, and head can appear to be at odds with one another, bent on pursuing separate, three-dimensional paths, but they do so with serene yet sensuous composure. I wrote in my program “rearranging their bodies.” Toogood is as alert as an animal. Changes in an unseen wind affect her, or a sound she heard in the distance that has nothing to do with Clams Casino’s ferocious score. The way she pauses or lets a movement dissolve or gathers herself for a new attack give her dancing the image of a life being lived that very instant.

I’ve written about Locomotor before (https://www.artsjournal.com/dancebeat/2015/04/running-backward-looking-ahead/ and https://www.artsjournal.com/dancebeat/2014/04/family-ties/. But every time I see it, something different strikes me. This time, Cori Kresge heroically took over Davalois Fearon’s role on relatively short notice, so that affected the mix of terrific dancers. And I thought more and more about the tracks these eight human locomotives trace on stage with their feet. They often enter the stage running—even leaping— backward, and it’s easy to wonder whether this is a rewinding of a former rush forward, or vice versa. Sometimes, several of them will loop around to exit just a little further upstage than they entered. Do they have an elusive destination or are the encounters just pit stops on a never-ending journey of which we’re seeing only a part?

The encounters are varied. I watch Toodgood and Joshua Tuason circling each other, Gino Grenek coming upon Barrington Hines and moving him around, nuzzling him, then dropping to sit on the floor while Hines exits. Jaqlin Medlock, for a second, makes me think of a little dog. I track the comings and goings of Nicholas Sciscione, Emily Stone, and Cresge. I hope Toogood will return and she does. Amid speed and endurance, moments of calm and tenderness spring up like dandelions beside a railroad line.

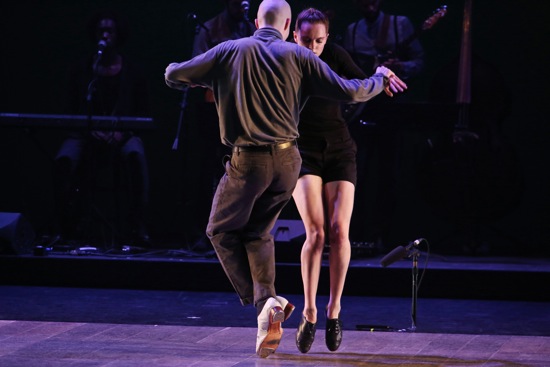

This Fall for Dance program ends with a burst of speed and noise that takes a different track from Petronio’s. Dorrance’s commissioned work employs twelve tap dancers including herself, as well as four onstage musicians and four additional singers delivering the score by Gregory Richardson and Donovan Dorrance. A glorious anthem of sounds—although sometimes, when all the dancers are going at once, their rhythm becomes almost assaultive, threatening to erupt around the edges.

The title, Myelination, can be defined as “the process of forming a myelin sheath around a nerve to allow nerve impulses to move more quickly.” That’s how responsive Dorrance and her dancers are. She doesn’t pester us with speed, but the onstage feet can move with uncanny rapidity, modulating among stamping, shuffling, clattering, sliding, tapping lighting—making the dancing sound like a fusillade of shots or stroking it into a caress of the amplified floor.

Dorrance is a whiz at structuring what is essentially a display of skill, playing on the ideas of competition and collaborative dialogues (riff answering riff), as well as designing formations, such as two people (plus one hidden behind them) creating a whizzing mandala of six legs. Dorrance and Elizabeth Burke cart away one dancer (I forget whom) so they can resume their duet. Dorrance breaks up a squabble and calms things down. Emma Portner is dancing fiercely when Warren Craft enters, and the two of them have a little bout of performing on the tips of their shoes, after which he gets to solo with some hard, intrepid stuff of his own.

It may seem from the above that Dorrance starred in Myelination, but that’s not so. Often, she’s tapping away in the line at the back. And throughout, the herd of dancers congregates and disperses. The music is wonderfully responsive to the dancing, quieting and slowing when that’s called for, sounding a call for something wide awake and feisty. Dorrance’s choreography for this new piece doesn’t interpret a well-known tune; the score is an atmosphere builder as well as a rhythmic support.

So an evening that began with rhythms both percussive and languorous ends with a rhythmic eruption that brings the audience to its feet.

How many people fell for dance this very night?

What is the misnamed D minor Suite for violin mentioned here, the D minor sonata for violin and keyboard or the D minor solo sonata? Neither is a suite. And the solo work (if that’s the one) is not devilish. It’s mostly transcendent music that puts you within sight of heaven. It’s kind of lousy writing to describe it as Jowett does.

I (Jowitt, note correct spelling) erred in not questioning the music credit as given in the program. Adding to the confusion, a video of Ballett am Rhein’s production of van Manen’s Solo, notes that it is performed to the Courante and Double from Bach’s Partita No. 1 in B-minor. I will do some additional research before correcting the text.

The San Francisco has confirmed that an error crept somewhere along the line. The music in question is indeed from Bach’s Violin Partita No. 1 in B-Minor. The correction has been made in the review.