The José Limón International Dance Festival at the Joyce, October 13-25.

José Limón’s Mazurkas. (L to R: Elise Drew Leon. Kathryn Alter, and Kristen Foote. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

José Limón was choreographing right up to the end of his life. His last dances, Orfeo and Carlota, premiered in 1972, the year of his death at 64. Those two works are included in the Limón Dance Company’s 70th anniversary celebration, now entering its second week at the Joyce Theatre. So is one of his earliest surviving dances: Chaconne (1942), a solo for himself set to a selection from J.S. Bach’s Partita No. 2 for Unaccompanied Viol.

The company’s season is billed as the José Limón International Dance Festival, and scattered among its six different programs are other companies, guest dancers, and student groups performing works from the Limón repertory. Some come from as far away as Venezuela and Denmark. Two dancers from the Bayerische Staatsballett were prevented from appearing by U.S. immigration authorities. One group of male students traveled from the University of Arizona at Tucson to dance Limón’s 1970 The Unsung. Others learned dances in New York City institutions (Juilliard and NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts). In all, fourteen of his works are represented, many of them staged and coached by former company dancers. A massive accomplishment by the company’s artistic director, Carla Maxwell, and its executive director, Juan José Escalante.

One name listed in the program’s “Who’s Who in the Company” section belongs to one of the great choreographers in the modern dance pantheon and a vital part of the company’s history. Doris Humphrey’s performing career was cut short in the mid-1940s by crippling arthritis, and the company she co-directed with Charles Weidman fell apart. Humphrey had been a mentor to Limón when he was a young dancer in that group, avid to choreograph. The Limón Dance Company made its debut in 1946, with her as an advisor and contributor. Her terrific 1949 Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejías, a solo for him and two participating women (they spoke lines from Federico Garcia Lorca’s great eponymous poem), celebrated Limón’s fascination with bullfighters—a fascination that in some subtle ways shaped his own style. With his powerful torso and quick-stepping feet, he often appeared to be charging into dance, swerving in avoidance, whipping around in confrontation with his own demons and those of the heroes he played—figures such as Othello, Judas Iscariot, Eugene O’Neill’s Emperor Jones, Julian the Apostate.

As a choreographer and teacher, he drew on Humphrey’s technique of Fall and Recovery—the breath-caught suspensions that end in a plunge to the floor and rise again, the beautiful, lush curve of the dancing body, as well as its jagged, off-balance moments. Humphrey was a humanist, who also thought in terms of architecture. Limón learned from her how to create choreographic structures that grew, organized, crumbled, and rose again—metaphors for human cooperation, dissent, and harmony. And he understood how these structures could serve dramatic intent.

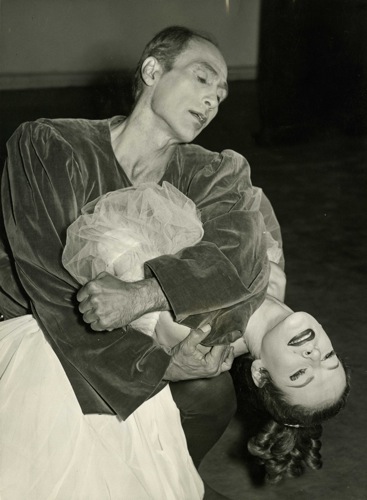

An earlier cast in José Limón’s The Moor’s Pavane: (Standing, L to R: Carla Maxwell, Carlos Orta, Bradon McDonald; supine: Roxane D’Orleans-Juste.

His 1949 The Moor’s Pavane is a marvel of a dance set to selections from incidental music written by Henry Purcell (1659-1695) for two plays, The Gordion Knot Untied and Abdelazzar, or the Moor’s Revenge (Humphrey found the music, and Simon Sadoff arranged it). Many companies have performed it, as well as many unlikely dancers—eg. Rudolf Nureyev and Erik Bruhn squaring off as The Moor and His Friend (Limón avoided using the names Shakespeare gave the characters in his Othello, perhaps to make them more universal).

Limón once wrote that he worked on the idea for three years. That shows. Since Shakespeare’s tragedy consists almost entirely of two-character scenes, Limón pared his cast down to four dancers and used the stately pavane form to indicate passion restrained by public courtesy, as well as the interdependence of Shakespeare’s Othello; his wife, Desdemona; his military subordinate, Iago; and Iago’s wife Emilia, who is Desdemona’s servant. The meet and bow, retreat, and join in a revolving circle that you can imagine as the wheel of fate. Treachery and jealousy disrupt that balance. You know the tragic result.

The opening night performance of the work (finely directed by Maxwell) could move you to tears—so nuanced, so somehow real the performances. Francisco Ruvalcaba has danced the role of the Moor for some time now, and in a theater the size of the Joyce, he conveys with magnificent subtlety his unwillingness to believe that his beloved wife has been unfaithful, his growing suspicion, and his fatal rage—first at Iago, then at Desdemona. Durell Comedy has the lean, almost serpentine wiliness that its originator, Lucas Hoving, brought to the role of Iago, the supposed friend. Comedy is a charismatic performer and excellent dancer (and certainly proved that in spades in his solo as Eros in Limón’s The Winged), but occasionally in The Moor’s Pavane—mostly in the small transitional steps—he loses a little of his knife-sharp accuracy.

Logan Kruger’s lovely Desdemona is both innocent and eager to please; were she to speak, she would be asking many times, “What does my dear lord wish of me?” In the second-night cast, the company’s associate artistic director, Roxane D’Orleans-Juste, is gentle and questioning in the role, but less naïve. Limón conceived the misguided Emilia as a sensual woman, and both Kathryn Alter and Kristen Foote bring that out excellently. In a way, Emilia is the most complex of the four. She loves her mistress, but craves the favor of her husband. He’d like her to steal the handkerchief that Othello gave to Desdemona? No problem, and no questions asked. But when that talismanic handkerchief leads to Othello’s jealous rage and Desdemona’s murder, the dancer playing Emilia has to show both her dawning realization of her own complicity and her resultant fury and grief.

On opening night, The Moor’s Pavane was bookended by two works choreographed in 1958. Missa Brevis premiered in April and Mazurkas in August. Both grew out of Limon’s profound experience of Poland (then behind the “Iron Curtain”), acquired when his company performed in Poznan, Wroclaw, Katowice, and Warsaw on a 1957 European tour sponsored by the U.S, State Department. He saw populations still struggling to rebuild cities destroyed in the bombing raids of World War II. Of the citizens he met, he wrote, “There was no rancor, no bitterness. Only a tremendous resolution, a sense of the future. . . .I am in awe of these brave people.” The music of the same name by Zoltan Kodály is said to have received its premiere in the basement of Budapest’s battered Opera House.

A Catholic Mass in time of war had to be brief. The score, with its thundering organ chords and voices lifted in prayer, lasts around a half hour. It was Limón’s first major work for an augmented company (I was among the members of Juilliard Dance Theater who took part in the process and the first performances). Anyone seeing it now might think that Limón had planned to be an architect rather than a painter. In the “Introitus,” three women are lifted, one after the other, above the huddled crowd by unseen hands; they stand straight and motionless, their arms by their sides. It’s as if beams are being raised by community effort. At another point, pairs of men run, holding women overhead in flying positions, like homemade angels. The circling chains of men and women, their clasped hands held high, build images of steeples and windows. When dancers swing one leg to pull them into half turns, you think of tolling bells. But Limón doesn’t present religious images as distant holy visions. When a woman (the eloquent D’Orleans Juste) emerges from the crowd to dance the “Crucifixus,” her bunched-together fingers stab her own body and her hands are laid across her chest when men lift her high and carry her away.

Ruvalcaba plays the role Limón crafted for himself: the outsider, the agnostic, struggling with his own feelings, drawn in spite of himself into this dauntless community. In the beautiful “Benedictus,” he dances with two women (D’Orleans Juste and Foote), both supporting them and dancing close between them—one with them.

The exulting crowd forms and disperses, creating patterns and erasing them; out of these, three may emerge to dance together or a soloist be left to a private utterance that draws others in. The “Hosanna” begins and ends with a woman (Alter) alone. (The original background image of s skeletal church would not work at the Joyce, but I also regret an oddly timed fade-out in the otherwise excellent lighting by Steve Woods, executed by Lauren Libretti. I have a memory of Betty Jones in 1958 and the light diminishing until for a few last seconds, a pin spot suspended her glowing face in darkness.)

Mazurkas, the program’s opener, celebrated Limón’s Polish experience in a blither way. While Michael Cherry plays Chopin mazurkas on the piano, seven white-clad dancers come together to celebrate being in that place and moving to music in a sprightly, often vigorous 3/4 meter. Once or twice, the pianist plays the lilting melodies with no dancers in sight and only the cyclorama suggesting a sunlit sky or one at dusk. Sarah Stackhouse staged and directed the revival of the sweet-natured, but vigorous work. Trios or dancers promenade arm-in-arm, meet and greet, separate into couples. I’m especially fond of the playful duet danced by Elise Drew Leon and Aaron Selissen. In one solo, Comedy claps his hands and stamps his feet with fervor. Ruvalcaba, in another solo, dances full of thought, twisting as if to gaze at different spots on the ground.

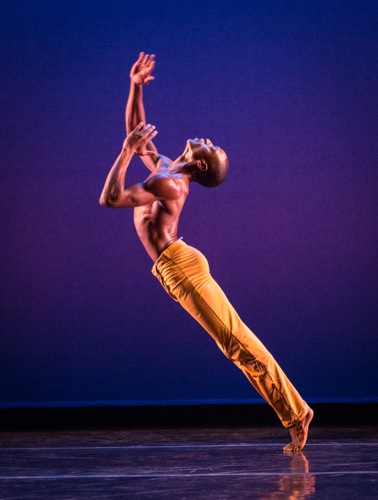

Doris Humphrey died of cancer at the end of 1958, and Limón was on his own. Among the works he made after this, were ones for larger groups, taking advantage of students in the Juilliard School where he taught and also ones that he created for members of his own company, as if fascinated by their individual qualities. The Unsung (1970) featured the men in his company. For them he created eight solos in honor of a pantheon of “defenders of the American patrimony;” the first was Metacomet, the last Geronimo (only seven could be performed at the Joyce because of a last-minute injury to Selissen).

José Limón’s The Unsung. (L to R): Ruka Hatua Saar, David Glista, Ross Katen, Durell Comedy, Victor Gonzalez, and Mark Willis. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The dance is performed without musical accompaniment, but the solos and the group passages that begin and end the piece and engineer transitions between the solos use the floor as a drum. The men’s feet strike the floor or brush against it. Frequently they step out on one deeply bent leg and smack the ground behind them with the arched foot of the other leg. You feel the push that sends them into the air as a silence, their fall from a balance as a soft percussive beat. That their spread fingers held above their heads at times to hint at feathered headdresses doesn’t seem corny or pictorial, and the dancing celebrates not only the Native American chiefs named, but the men for whom the solos were created and the men who dance them now. You can be impressed by the arching spine of Mark Willis or the bent over spins with wheeling arms that Kurt Douglas sends around the stage. Ross Katen’s comparative serenity contrasts with Comedy’s big side-to-side tilts. Three of the soloists in the cast of nine are members of the Royal Danish Ballet, so you can can also admire Charles Anderson’s slide into a near-split, Gregory Dean’s handstands and back somersaults, and Gabor Baumbach’s deep lunges. Among the many other imaginative passages of dancing, performed by all with dedication.

When I first saw The Winged in 1965, it, too, was danced mostly in silence, with only fragments of incidental music by Hank Johnson. It’s said that Limón wasn’t satisfied with that; when Maxwell set the piece on Juilliard students in 1995, a score was commissioned from Jon Magnussen,. The music is imaginative, sometimes cacophonous, full of voices that can sound like wind or birds’ cries or human muttering. It’s distractingly rich at time. Still, Limón’s piece is rich too. Humphrey might have urged condensation, but you can sense the choreographer drunk with possibilities—urging his splendid dancers into variegated images of flight and other aspects of life among the winged, including those from Greek myth. They appear in squads, rushing onto the sky of the stage and off it, one group circling another. There’s a loving “Nuptial Flight, admirably danced by Elise Drew Leon and Ruka Hatua-Saar. Hatua-Saar and Comedy duel by slashing and rippling the air between them; they have to be separated by others. Seven women as ferocious Harpies feed on their own lifted legs. The splendid Foote appears as a powerful, stony Sphinx, succeeded by Douglas as Pegasus in a stunning piece of choreography. Sometimes I forget how imaginative Limón could be with movement without deviating from the essential heroic nature of his style.

One of my favorite images in The Winged’s ten sections occur in two moments when the main action onstage is framed by men’s heads—only their heads— protruding at floor level from behind the side curtains to gaze at the goings-on. I have no idea what Limón had in mind. And I quite like not knowing.

I regret not seeing more of this celebration of a major 20th-century choreographer’s work. Maxwell, who may retire soon as artistic director has guided the company since 1978, making a number of astute choices in terms of acquiring works by other choreographers that fit gracefully into the Limón repertory. However, it’s splendid for New Yorkers to be able to revisit so many works by the master himself, sensitively coached and fitted to dancers of various nationalities and ages.

It’s cavalier and, to my mind, incorrect to speak of Limón’s works as dated. To be sure, they belong to a certain period of time in dance history, but they deal with timeless topics, and the best of them do that with passion, craft, and wisdom about the human condition.

Your account of these dances is lovely and characteristically sensitive; I saw the same shows and saw them the same way.

One note, though, about “The Moor’s Pavane”: You say that Limon conceived of the Emilia figure as sensual. However, the original “Friend’s Wife,” Pauline Koner, wrote in her memoir that she herself choreographed her own part, as Limon and Humphrey “allowed” her to do in all of their rep. Koner describes at length and in detail her process for working on the character and she adds that she takes issue with critics who insist that the Limon Emilia is “sensual” rather than “sensuous.” This doesn’t mean that Koner is “right,” but it does mean that she had strong opinions about that part and that they should be part of the mix–or, in this case, the legacy.

“Humphrey might have urged condensation”

As she so often did!