Camille A. Brown & Dancers premieres Black Girl: Linguistic Play at the Joyce Theater.

How fast their feet are! Skittering, stepping, bouncing up and down, kicking out those feet, six women dance as if the ground itself is both untrustworthy territory and something that needs mastering. Camille A. Brown calls her new, evening-long work Black Girl: Linguistic Play. She and her colleagues rarely use their tongues. When a woman dances her own reverie or two of them “converse,” the feet do the talking.

In a program note for Camille A. Brown & Dancers’ season at the Joyce Theater, the choreographer mentions the influences on Black Girl: Linguistic Play. One was Kyra Gaunt’s book The Games Black Girls Play, and the other was the games that Brown herself used to play when she was growing up. Not on an i-Pad, but on city streets, where jump ropes twirled, and girls chanted the rhymes that helped them keep up in time with those two ropes arcing in Double Dutch. She mentions clapping games (like “Jig-a-low”) and Red Light Green Light. In their various ways, these could offer lessons in endurance, rhythmic skill, quick-wittedness, and vulnerability. You had to be intrepid, you had to be quick, or you were out.

Brown has mentioned her impatience with stereotypes, such as “the angry black woman” and “the strong black woman.” Those women do exist, but there are shadings and contradictions within their anger and within their strength, just as there are black women with many different qualities and different temperaments: warmth, vulnerability, humor, sharp-wittedness, serenity, a poetic view of the world, and more.

There are no tragedies in Black Girl: Linguistic Play and no plot-filled narratives, only solo meditations and three successive encounters between two women: Brown and Catherine Foster, Beatrice Capote and Fana Fraser, Mora-Amina Parker and Yusha-Marie Sorzano. The women in each pair think, size each other up, copy each other’s moves, explore friendship. But, although all six marvelous dancers are expert at depicting temperament and “behavior,” Brown chooses to expose them and their relationships primarily through movement and the pauses that mark the rhythms of everyday life.

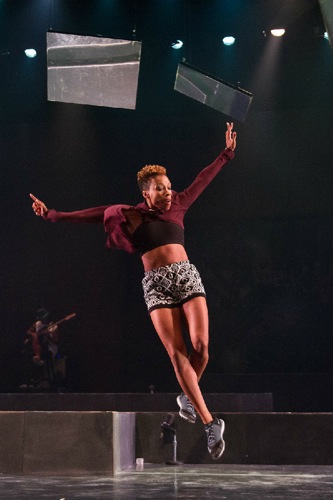

The entire production both abstracts and distills real life in powerful ways. Revisiting girlhood, the dancers wear bright, idiosyncratic clothes and dance in a landscape that conveys the instability of life on playgrounds, pockmarked city streets, and lonely sidewalks. Running over the big, irregularly set blue-gray platforms of different heights (set design: Elizabeth C. Nelson), a dancer can drop down into a chasm between them that’s not visible to everyone in the audience and pop up on another platform, or leap between two platforms. Someone can sit for a while on one of them, as Brown does in the opening sequence, and dangle her legs over its edge. Behind the platforms, a little to one side, a “wall” displays its graffiti, and mirrored overhead panels capture fragmented birds-eye views.

The music—most of it composed by Scott Patterson (piano) and/or Tracy Wormworth (bass)—wonderfully conveys not only atmosphere but the shifting rhythms of play and emotional climate. Performed by the two musicians in a far corner of the stage, the score is sensitive to change, knows when to fall silent, and when to create a ruckus. (Patterson and Wormworth also attack Radiohead’s “Everything in its right place.”)

Brown opens Black Girl: Linguistic Play. Here’s a girl trying things out, working them; small gestures fleetingly suggest checking her image, brushing her teeth, fanning herself. She climbs on a platform and jives around. Spectators laugh when she walks in place (maybe they’re remembering the moonwalk). Occasionally she looks up. She also puts her hands in white powder that has accumulated on one platform. Chalk dust from drawing hopscotch diagrams?

She’s ready to sit and watch Foster, who enters as an admired friend (or friend to be). There’s nothing tentative about this girl. Her feet fly, her hips shake. How could you not want to dance with her? A fist bump and Brown is accepted. Educated. They step out hand in hand. Foster lets out a barrage of steps and hand claps, inciting Brown to join in, and Brown does.

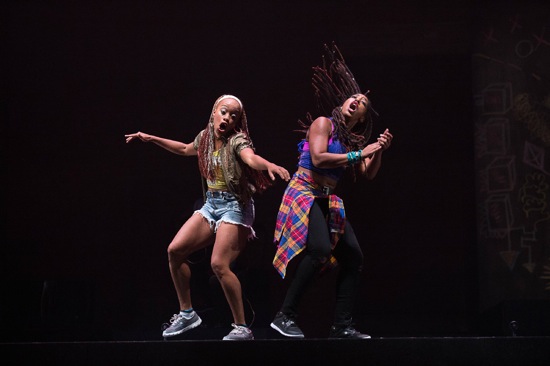

They exit when Fraser and Capote enter. These two are already friends. Side by side, on the highest platform, they check out the graffiti. They park themselves on the edge and play at watching tv. They get a little edgy with each other. One sulks. Later they squabble—all flailing limbs and fierce stares. But dancing is the thing—not, mind you, polished dancing. At one point, they both go crazy—flinging and swinging everything they’ve got. The musicians, who’ve played pretty sweetly during the first duet, egg them on. Near the end, Capote delivers a definitive statement: she sinks into a split. Throughout the duet, you feel a kind of nervous energy common to growing-up girls. What are they going to become? Is that the question driving them?

Brown and her collaborators are adept at dancing awkwardness and uncertainty, as well as the bravado that can conceal those. The third duet has a different quality, and the music for Sorzano’s solo sounds dark and urgent. She races over the platforms—braving the chasms and the heights. She gathers up some of the white powder (now it acquires a possible new significance), gets dreamy, and shoves it around. But she’s not alone. Parker stands apart, watching her run. A mother? An older, been-there sister? Tall Parker sits Sorzano down between her legs, holds her head, stops her frantic hands. The music falls silent. Think not just of restraining, but of cleansing.

Sorzano’s performance is the most nuanced and most moving one in the piece. Although both she and Parker do some hard dancing side by side, she stops and feels her own face, gets worked up again, calms down. I imagine her thinking, “What’s ahead for me?” The other four women, who’ve passed through on their own bold errands, stop and watch. They too, face adulthood.

Brown incorporated a post-performance discussion into the evening, beginning it only seconds after the curtain call. It clearly mattered to her that audience members stick around for it, and almost no one left. She asked people to contribute words evoked by Black Girl: Linguistic Play, and they did. “Sass,” “nostalgia,” “attitude,” “home,” “majestic,” “complex” were some of those offered. No one said “beauty” at the performance I attended, but it was there all right.

Lovely review Deborah, makes me hope White Bird brings Brown back to Portland next season. I wasn’t impressed the last time she and her company were here, I’m bound to say, way too didactic a program, although certainly heartfelt. This looks much more interesting–I’d like to watch those beating feet and all the rest.