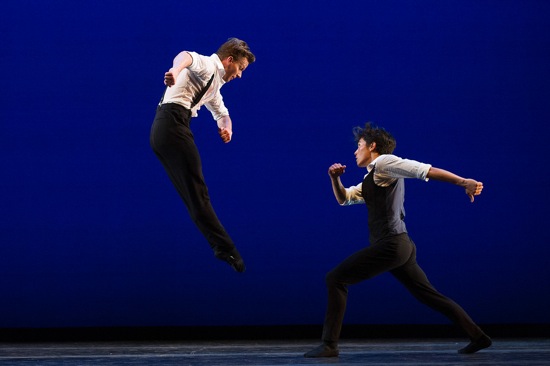

Sara Adams and Russell Janzen of Daniel Ulbricht & Stars of American Ballet in Justin Peck’s Sea Change. Photo: Maura Geist

Daniel Ulbricht has a mission in life that goes beyond being a buoyant, dramatically expressive principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. Forming and re-forming Daniel Ulbricht & Stars of American Ballet in NYCB’s off-season enables him to bring first-rate dancers to communities around the country. The group he brought to Jacob’s Pillow this summer for its second appearance there numbers eleven performers who cross the hierarchy of status: six NYCB principal dancers in addition to himself; Jeffrey Cirio, in transition to American Ballet Theatre from his position as a principal dancer with Boston Ballet; one corps de ballet member of that company (Shelby Elsbree); NYCB soloist Russell Janzen; and Sara Adams from NYCB’s corps. In Ulbricht’s mind, they are all stars, and all live up to his high opinion of them.

Don’t be deceived by the name of the company. Ulbricht’s choices of choreography avoid hi-tech displays of the sort that the word “stars” brings to mind. No Don Quixote pas de deux. No Act III pas de deux from Swan Lake, with its count-along load of 32 fouetté turns. And nothing too trendy or kinky. Instead, a masterwork by Jerome Robbins, two quartets by swift-risen choreographic artist Justin Peck, an iconic duet by Christopher Wheeldon, and (surprise!) a trio by Johan Kobborg, a former principal dancer with the Royal Danish Ballet and England’s Royal Ballet, and now director of the Romanian National Ballet.

In other words, a program of neo-classical works that show off the performers’ virtuosity and emotional range without resorting to flash for its own sake.

Robbins created In the Night for NYCB in 1970, right after making his return to the New York City Ballet with Dances at a Gathering (1969). Obviously he had fallen in love with more Chopin piano pieces that could fit into one ballet. While Dances at a Gathering seems to be happening in a sunny field, the three duets of In the Night occur in a featureless space overhung with stars—the dream world of the nocturnes that accompany it. Perhaps each of three couples might have escaped from a ballroom for more intimate exchanges; their courteous coming together at the end suggests as much.

I marvel at what Tyler Angle is able to convey with his partner, the lovely Sterling Hyltin. His focus is almost always on her, and if he isn’t looking at her, he is seeing what she sees, or what she has not yet seen. There are many complex lifts in this rapturous first-love ballet, but Angle shows little effort. He is as involved in what she does as a sapling that both supports and bends beneath the vine that spirals around it.

Violette Verdy, who danced the second duet of In the Night with Peter Martins at the ballet’s premiere, once said that she thought of this man and woman as comfortable and familiar with each other, yielding to the tempestuous passage in the middle of the music as a way of spicing up a relationship to keep it from (her word) “coagulating.” Or perhaps—as is often the case with Robbins—remembering a past episode. This made me wonder about Teresa Reichlen, who presents a cooler, almost stern image—perhaps as a way of matching her partner (Amar Ramasar), who subtly projects the dignity that his military jacket suggests. For some reason, Ramasar didn’t carry her offstage in the usual way, looming above him; whatever the glitch, he saved it by dropping her into his arms the way the man in the third duet carries off his lover.

Rebecca Krohn and Jared Angle perform this last, stormy duet. I hadn’t seen Krohn in such a role before, and she startled me. This is a wild woman, recklessly, angrily passionate with a patient, more stolid lover. She leaves, she returns, she throws herself at him. They stand face to face and stare at each other. At the end, she kneels at his feet. He snatches her up and rushes her away.

These are all marvelous dancers. At Jacob’s Pillow, they had to cope with a smaller stage than usual, as well as the poor sound emanating from an offstage piano (it turned to be not a baby grand, not even a full-sized spinet), despite the eloquent playing of NYCB pianist Susan Walters, who knows this ballet well. This iteration of Anthony Dowell’s costume design makes the women’s long full skirts so filmy that they take on a distracting life of their own.

Daniel Ulbricht aloft in Justin Peck’s Distractions, aided by (L to R): Russell Janzen, Amar Ramasar (hidden) and Jeffrey Cirio. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Ulbricht had the good sense to commission Distractions from Justin Peck in 2011 for a Santa Fe engagement of his pick-up group. This exuberant quartet for four men (Cirio, Ramasar, Ulbricht, and Janzen) shows what they do best in the way of athleticism (high jumps, multiple spins, etc.), but it’s beautifully structured and organized to suggest both camaraderie and competitiveness. Peck skillfully makes use of the contrast between large-scale and small-scale movements, between suddenness and flow, between motion and stillness.

The music for Distractions is Alexander Rosenblatt’s Paganini Variations—a contemporary response for solo piano to the same Paganini theme that Brahms tackled in the 19th century. Walters’ fingers get a workout. Although she’s still invisible, the dinky piano has begun its advance into the stage space, hovering upstage right, half on, half off, with its back to us.

The dancers are not easily distracted, but just as the music sometimes seems to fly into arguments with itself, the four can create a boil-up of activity by leaping here and there, each seeming to have his own ideas and choices. The costumes (by dancer Reichlen) go along with the men’s easy-going athleticism; white tank tops and navy blue pants with white bands at the calves. Each man shines in a solo, and Cirio and Janzen perform a duet side by side. Often, amid diversity, the performers suddenly drop—smoothly and almost miraculously—into unison. It’s as if, embroiled in a series of separate conversations about, say what to eat for dinner, they all suddenly come out with, “yes, eggplant parmigiana!”

Certainly we see what these remarkable men are capable of. Peck gives Janzen fast footwork and tricky jumps (like leg-whipping gargouillades). Cirio moves with reckless zest in his forays. Ramasar performs a splendid solo, bringing out all the nuances of timing—now a burst of footwork, now an uncannily slow pirouette. Ulbricht’s long adventure to a racing piece of music displays his high-jumping prowess. However, the four don’t overtly dance for us; they give the impression of doing what they do for the pleasure of one another’s company and for their own private delight.

Justin Peck’s Sea Change. (L to R): Jared Angle, Sterling Hyltin, Russell Janzen, and Sara Adams. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Peck’s other ballet, Sea Change, made in 2013 for the Nantucket Dance Festival and featuring two dancers from NYCB and two from Miami City Ballet, is a little less remarkable, but full of fine moments. On a program that features works either about dancerly competition or romantic love, this one joins In the Night as an exploration of what a man and a woman can do together on a calm evening when wonderful music seeps into their spirits. In this case, that “floor” is Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 20 in A Major, finely played by Craig Baldwin. Unlike the couples in the Robbins work, these on occasion dance the same steps at the same time, and each pair is very aware of the other. When J.Angle and Hyltin dance amorously together, Janzen and Adams watch them, and when the latter couple dances, Angle and Hyltin wander around the perimeter of the stage and keep their eyes on the action.

They’re dressed for a party in simple but effective outfits by Reid and Harriet. The women’s gowns move beautifully; underneath the long, full, dark skirts, Hyltin’s offers up a flare of underlying red fabric when she swings a leg, and Adams’ matching dress foams into green.

The space is a limbo. Sometimes I imagine the four characters thinking, “What are we doing here?” Nor are they always fluently, tranquilly in love. A passage for Hyltin and Angle turns tempestuous along with Schubert. I should have seen what was coming. Janzen and Adams—she hanging on him—advance toward a downstage corner where Angle waits alone. Janzen has the air of a sleepwalker. Suddenly there is indeed a quite sudden sea change. A few seconds later, Adams is holding Angle’s hand, and the two of them are walking slowly toward the audience, while Hyltin and Janzen watch. The end.

Krohn dances with T. Angle in Wheeldon’s After the Rain, a duet drawn from his longer 2005 ballet of that name and made famous by Wendy Whelan and Jock Soto. Kurt Nikkanen joins Walters to play Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel, with the violin singing its melodies above the piano’s sweetly insistent three-note phrase. The relationship between the two instruments becomes slightly denser and more intimate toward the end, but the two dancers are gently familiar with each other from the start, when they stand and rock from side to side as if preparing to embark on a voyage together. Krohn’s hair is loose, and she’s barelegged; her slippers are soft. Angle wears no shirt. Wheeldon’s choreography is seamless and almost weightless, with occasional curious moments of awkwardness, and the dancers perform it with the mixture of simplicity, tenderness, and ardor that it asks for.

Johan Kobborg’s Les Lutins. Daniel Ulbricht (L) feints with Jeffrey Cirio. Photo: Christopher Duggan

The piano finally emerges for Kobborg’s Les Lutins (The Goblins). It sits unashamedly downstage right facing us, and Baldwin plays with his back to us. He and Nikkanen perform two lively 19th-century pieces—a Caprice by Henryk Wieniawski and Antonio Bazzini’s Ronde des Lutins—that provide recreational stimulus for two guys and, oh yes, a woman. The first music sounds like a mating of bumblebees, and Ulbricht dances to it with brio. He’s a small man who jumps big, but without visible effort. When he launches a double or triple turn in the air, his legs are pressed so tightly together for so long that he resembles spinning needle. Kobborg has choreographed good-natured competitive behavior into the ensuing duet for Ulbricht and Cirio. They take each other’s measure, shrug, avoid (just) shaking hands; one gives the other a sly kick in the pants. Mostly, they dance brilliantly and roguishly at each other.

When Elsbree appears, she’s garbed just like the men: white shirt, black pants, suspenders, black shoes (costumes by Ulbricht). She’s both flirty (a little hip action enters the picture) and up to whatever moves the men propose (well, not the dazzling flip in the air with which Ulbricht topped Cirio). Some of the action by all three moves back and forth on a diagonal toward Nikkanen (earlier, the men have acknowledged him), and the end, Elsbree pushes her way between her suitors–knocking them both down—and gestures to Nikkanen. Her heart belongs to him and his music.

(L to R): Shelby Elsbree, Daniel Ulbricht, and Jeffrey Cirio in Johan Kobborg’s Les Lutins. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Watching the Royal’s Alina Cojacaru perform the trio with Steven McRae and Sergei Polunin (www.youtube.com/watch?v=iiZq6AQpcAg), you can see that the music is what’s turning her on from the beginning. How she loves dancing to it! And, shyly flirtatious as she is, she seems simply to be a good sport about the men’s eagerness to lift her and turn her and get her to choose between them. Elsbree, a very captivating performer, doesn’t show that joy in the music early on.

Except for In the Night, all the dances on Daniel Ulbricht & Stars of American Ballet’s at Jacob’s Pillow are short. The remaining four succeed one another without a second intermission. The dancers show us their skill, their warmth, and their charm as part of a mostly light-hearted package. The ballets provide passion as well as wit, but avoid angst. A smart tactic on Ulbricht’s part. There are a lot of violent pas de deux and pas de trois these days that make you think more about calling the cops than feeling the joy that’s been intrinsic to dancing from whatever dark age birthed it.

As usual, your review is insightful and makes me wish I cold have seen the show. This is very nit-picky point: you refer to the men’s tank tops “wife-beaters,” which — especially in the context of your upbeat take on the program — seems sexist and outdated.

Thanks to you, Gus, for pointing this out. Trying to seem up-to-date always backfires. Especially when you don’t know for sure what’s old hat. I’m making the change right now!!

I especially love Deborah’s last paragraph, but the human tone of this program conveyed above warms my heart and soothes my soul. Clearly the audience is not subjected to emotional self-indulgence,or the deployment of dancers as automatons, or gratuitous and solipsistic angst and thank you Daniel Ulbricht for that at the very least. Beyond that, she makes me remember Oregon Ballet Theatre’s performances of “In the Night” with nostalgia and affection, for they too danced this ballet very well.

Your article and Martha’s comments got me thinking about trends in contemporary ballet partnering. When stern, punched dance behavior began to take hold in the 1980’s, I turned to my theater companion and said “It looks as if the dancers had an argument in the wings and brought it onstage”. The audience was left in the dark.

In contrast, Jerome Robbins created ballets that build suspense. He used angst sparingly. Bravo to Daniel for providing variety in his program.

A handsome and insightful review of an excellent evening (I love the evolution of the piano). The intimacy with which the audience can experience In the Night at Jacob’s Pillowis breathtaking, and you’re right that Krohn is extraordinary in the third pas (she is in the After the Rain pas, too, taking what looked existential with Wendy Whelan and making it erotic). You’re the Robbins expert, but is there anything more touching in all his work than the moment in In the Night’s finale when the women suddenly meet and politely bow to each other? The sophisticated decorum with which they must repress their erotic feelings for the sake of the social fabric always brings a lump to my throat. Thank you again, Deborah.