Gauthier Dance//Dance Company Theaterhaus Stuttgart Comes to Jacob’s Pillow.

L to R: Luke Prunty, Juliano Pereira, Anna Süheyla Harms, Anneleen Dedroog, Maria Prat Balasch, Florian Lochner, and Maurus Gauthier of Gauthier Dance//Dance Company Theaterhaus Stuttgart in Cayetano Soto’s Malasangre. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Only nine of the fourteen members of Gauthier Dance//Dance Company Theaterhaus Stuttgart were on hand when this Germany-based company made its United States debut at Jacob’s Pillow this July, and only once during its program (in Cayetano Soto’s (2014) Malasangre) did more than three people appear onstage at the same time. There may be a reason for this. Although the repertory includes full-length ballets, one of the company’s incarnations is Gauthier Dance Mobile, which presents dances in small spaces, such as those in youth centers, nursing homes, hospitals, et al. Gauthier Dance has only been in existence since 2007, but has become extremely popular since its founding by Eric Gauthier, then a soloist with the Stuttgart Ballet.

The Canadian-born Gauthier is not the ensemble’s sole choreographer. The Jacob’s Pillow program offered works by six others, Alexander Ekman, Alejandro Cerrudo, Po Cheng Tsai, Johan Inger, Marco Goecke, and Soto. The seven fairly brief works bled into one another with only the briefest of blackouts to separate them. The dancers also form an international group—born in Spain, Italy, Brazil, Switzerland, Australia, and, yes, Germany. All of pieces are light-hearted, designed to show them off as both virtuosi and as charming, fine-looking people who like and admire each other a lot. They applaud one another during curtain calls and take their final bow of the evening with their arms around their colleagues.

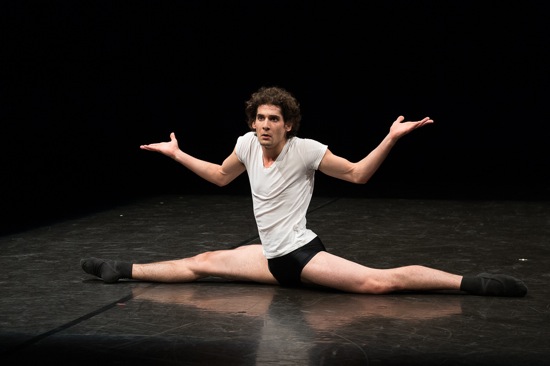

Gauthier choreographed Ballet 101 in 2006 before founding his company, and (performed, I believe, by him) it immediately won prizes. Maurus Gauthier dances it now—with skill, endurance and wit. It makes for a terrific program opener. The premise is that, goaded by a male voice that offers bits of information about the origins of ballet, he will demonstrate ballet’s basic positions (more than five, since he cycles back through the centuries and Jean-Georges Noverre). But this unseen ballet master is a capricious fellow. He puts the dancer through a hundred steps—some balletic, some not so much, some very strenuous—with occasional warnings. #40, notes the voice, looks a lot like #25 (a split); M. Gauthier shrugs and grins at us.

Next, the unseen boss announces that he’ll call out the numbers at random. and the dancer will obey. This is, of course, a fiction, but I couldn’t help wishing that each recited number preceded the desired response by a second or two seconds, rather than their occurring simultaneously. Anyway, the performer dances to beat the band. Choreographer Gauthier delivers a comic ending. After M. Gauthier explodes into a collapse and the lights go out, they come on to reveal a neat arrangement on the floor of dummy limbs and a headless torso. I guess that’s what happens if you get as far as 101 moves. The dancer, smiling mischievously, exits with the torso under his arm.

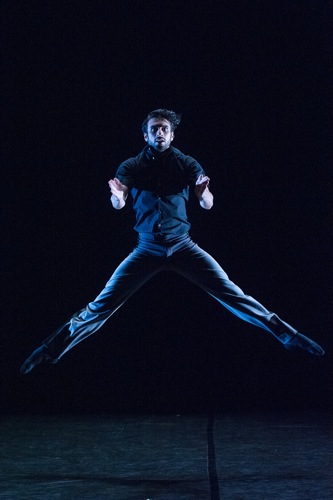

Showy male dancing plays a big part of this program. In the second-to-last number, Goecke’s I Found a Fox (2014), Rosario Guerra dances to Kate Bush singing “Suspended in Gaffa,” with its repeated (hard to make out) variants of “Can I Have It All Now,” its driving beat, and its screamy little-girl chorus. This is a solo that requires Guerra to be both nimble and stiff, as if animated by some clockwork function of the song. He makes little, swift repeated jabs of movement, his elbows poking the air, his hands flicking and flipping it.

Cerrudo’s PACOPEPEPLUTO (another inscrutable title) is a trio for three men, created in 2011 for Hubbard Street Dance Chicago (of which Cerrudo is resident choreographer). The guys dance, wearing only tight, skin-colored dance belts, dance mostly alone, accompanied by Dean Martin singing two songs, “In the Chapel in the Moonlight” and (can you believe it?) “That’s Amore,” and Martin impersonator Joe Scalissi delivering “Memories are Made of This.” Luc Prunty begins alone, protectively holding his crotch for some reason. There’s nothing shy about his dancing however, and Cerrudo gives him some handsome and interesting steps to do; he’s earthy—sinking down to launch himself into big sweeping or rising moves—and silky in a highly muscular way. Florian Lochner succeeds him, and begins by copying some of his moves, before swooping into a routine of his own. The third, Juliano Pereira rushes in for more display. The three do interweave intermittently, and all dance splendidly. There’s no stopping the men and very little punctuation to the choreography. Without fanfare, they’re nevertheless out to stun us, and they do.

Three items on the program are male-female duets. Inger’s Now and Now, created for the company this year, features musical selections by Arvo Pärt, Nangpa La, and Erik Enocksson. Here we get a little glimpse of the non sequiturs that are trendy in much contemporary choreography. Why should this handsome blond man (Lochner) arching under a spotlight (lighting design by Mario Daszenies) suddenly walk away from us as if he were an ape. Is he wearing black socks just so he can slide his feet? Why in her solo should Anna Süheyla Harms take big, spraddled steps, make twitchy gestures, and embark on a game of hopscotch for five seconds. Nevertheless, these two are beautiful and expressive as they spar, leaning apart, dancing swiftly and combatively around each other. For their mutual pleasure, he walks his fingers down her arm and elsewhere.

But Inger has a statement about gender to make and lays it out cleverly. The two start crawling over each other, unobtrusively divesting themselves of clothing as they travel to a corner under flickering light. But when they rise and pick up the scattered garments, she garbs herself in his black trousers and jacket and he puts her little black dress on. They make big crooked, agitated movements, but when he repeatedly attempts to touch her, she knocks his hands away. The duet ends with them holding each other in a ballroom stance, but on their knees. The lights go out for a second;, when they come on again, she has vanished. Maybe she melted into him?

Ekman’s Two Become Three (2011) is more humorous. And Annaleen Dedroog and Guerra play it to the hilt. The bonus: it’s accompanied by Chopin’s Nocturne in B, Opus 9, no. 3. There’s also a standing lamp that seems to be there only so it can be switched off to end the duet. An unseen voice tells us what a cool guy Guerra thinks he is; sometimes the correspondence of text and movement elicits laughter. At times, he plays with Dedroog as if she were a versatile doll someone had given him. Like a lion tamer, he induces a trick; he holds up his arms in a circle, and she sort of dives through them. Dancing together, they become euphoric, and when they stop, it’s to yell “I LOVE YOU!” at each other. Their facial expressions are integral to the choreography, and they disarmingly indicate delight, uncertainty, and worry as they back up taking turns cradling a naked baby doll that has fallen from the rafters.

Garazi Perez Oloriz with Maurus Gauthier’s legs in Po-Cheng Tsai’s Floating Flowers. Photo: Christopher Duggan

The third duet, Po-Cheng Tsai’s Floating Flowers, which premiered in Hong Kong last year, is based on the same gimmick as Pilobolus’s memorable Untitled (1975). Garaz Perez Oloriz—she of the long, blond ponytail—is standing in a spotlight, wearing an ultra-bouffant white gown over a hoopskirt. She moves her arms with serpentine fluidity, flicks her wrists, leans her body, gazes around. All of a sudden, she’s very tall indeed. Brawny male legs belonging to an otherwise unseen man on whose shoulders she is sitting (M. Gauthier) dance her around the space, sometimes in big, thumping runs that no elegant lady would countenance. The pulsing music with melodic overlays is cellist-composer Zoë Keating’s “Legions (Reverie)” and “We Insist.” In one of the moves that I wish the choreographer had resisted capitalizing on, Perez Oloriz arches so far back that she hangs weirdly over her carrier. If this is a “floating flower,” a motorboat must be running over it.

Gauthier eventually emerges, wearing his own white hoopskirt, and together the two billow attractively and athletically—their costumes giving them the air of wind-tossed blossoms.

Malasangre (2014) is performed to La Lupe’s rendition of three songs, including the famous “Guantanamera” (remember Pete Seeger singing it?), a setting of words by the Cuban poet José Martí. Soto created the work in homage to La Lupe (Guadalupe Victoria Yoli Raymond), who died in 1992. The company’s engaging dancers (minus Perez Oloriz and plus Maria Prat Balasch) come and go, form small squads, dance with partners, and at times lip-synch the words of the songs. One woman (I forget which) has an apparent temper fit and backs out, squeaking in rage. The choreography is supported by a lighting design (by Soto and Daszenies) that fills the stage with fifteen circles of light onto which stagehands have strewn what look like little crumpled pieces of gray paper (maybe ashes?). The lights are obedient to the full-spirited, ardent, beyond-strong dancing; one row of them may go out, or all may be extinguished but one. At the end, when all onstage are mouthing the words to “Guantanamera” as they dance, the lamps begin flickering on and off, on and off.