Pam Tanowitz Dance and the FLUX Quartet opens Bard SummerSpace 2105.

Stuart Singer (L) and members of Pam Tanowitz Dance in Broken Story (wherein there is no ecstasy). Photo: Cory Weaver

The featured composer at Bard SummerScape 2015 is Carlos Chavez (1899-1979), and in July and August, the 26th annual Bard Music Festival will devote its performances and symposia to him and his contemporaries. On June 27, Summerscape opened at Bard College in Anandale-on-Hudson with a taste of his music. Choreographer Pam Tanowitz included on her program a brand new solo that she created for Ashley Tuttle, set to the composer’s Sonatina for Violin and Piano—not a piece that alludes to his Mexican cultural identity.

Tanowitz is remarkable for her skillful reimagining of formal devices, such as repetition, unison, counterpoint, retrogression, etc. and for the ways in which she honors and utilizes ballet steps, while teasing them in various ways and introducing non-balletic ones to jostle them a bit. Tuttle, a former principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre, a member of Twyla Tharp Dance, and a starring performer on Broadway in Tharp’s Movin’ Out, has the intellect and the body memory to tackle almost anything.

In Solo, Tuttle shares the stage with violinist Pauline Kim Harris and pianist Michael Scales. She’s dressed becomingly (by Reid Bartelme) in footless purplish tights and an elegantly cut peach-colored tunic. Glowing in Davison Scandrett’s fine lighting, she begins in place, working her feet in their pointe shoes a bit. Oh those feet! Beautifully arched and subtly used, they remind me of Balanchine’s advice to his women dancers: they should use their feet as if they were akin to an elephant’s trunk—complicated, flexible appendages that could move with delicacy as well as power.

Tuttle dances as if she’s trying out steps or remembering them, rather than “performing” them for us. We watch her, prepared for anything, and “anything” appears in perfect harmony with the ballet steps you might expect. Knocking, in passing, on an imaginary door or spending a few moments prone on the floor are elements in a texture that includes arabesques and pirouettes. She may flex her feet on a jump, when you might expect them to be pointed—no big deal. She passes behind the violinist and around the piano, then places a hand on that instrument as if it were a studio barre, in order to engage in a little supported work.

What we see is a superb dancer firmly and gently on the prowl in a territory both familiar and unfamiliar. She wears her virtuosity as if it were made of silk.

Maggie Cloud and Dylan Crossman in Tanowitz’s Broken Story (wherein there is no ecstasy). Photo: Cory Weaver

Tanowitz’s Broken Story (wherein there is no ecstasy), which opened the Bard program, begins with a solo by Dylan Crossman that is equally thoughtful. He’s no ballet dancer—ruggeder in what he does, but wonderfully precise. He’s a lean man, and when he swings a leg around, you may think of a knife slash. A former member of Merce Cunningham’s company, he’s alert to all the nuances in a sequence of movement—when to suspend a step, when to slow it down, when to turn in into an exclamation point. Verbs like “veering,” “vaulting,” “tilting,” “careering” come to mind. Melissa Toogood (another Cunningham alum) enters, gazes at him, and backs out. No point in bothering him now.

He dances to 1655, by Caroline Shaw, the first of three contemporary pieces to be played by the FLUX quartet (Tom Chiu, violin; Conrad Harris, violin; Max Mandel, viola; and Felix Fan, cello). The other works are David Lang’s almost all the time and Ted Hearing’s For David Lang. The quacking viola that begins 1655 hints at the interesting things to come—rhythmic, fragmented, with lots of space between groups of sounds. In Crossman’s solo, as in all Tanowitz’s work, her musicality is evident, although not wedded to the beat. Watching and listening, you’re aware of echoes and sudden congruencies, as if dance and music are two compatible fellow travelers who have much in common despite individual agendas.

The title Broken Quartet sums up the ambiance of what is essentially a foursome, but one in which the dancers rarely perform in clear-cut unanimity. And all four performers have moments in which they stand and stare, as if not yet sure how they fit into an established pattern. Maggie Cloud arrives, looks at Crossman, and starts dancing when he approaches her. But he returns to his initial phrase (which he does intermittently throughout Broken Story), and she wanders into counterpoint with him before the two fall briefly into unison. She leaves and crosses the stage behind a scrim, where Scandrett’s lighting has created a hazy sunlit corridor, then re-materializes. Definitely no ecstasy. Once, when she’s frozen on her spot, he simply picks her up and puts her down elsewhere.

In the intermission after this piece, a friend I ran into spoke of how much she loved watching dancing. Just watching it for what it was, what it awakened in her own body. She wondered whether there was something she should be understanding and doesn’t. No, I told her, especially in a non-narrative dance like this. Nevertheless, since the materials of dance are human beings, their movements inevitably suggest feelings and physical sensations that we all have. It wouldn’t surprise me if I learned that Tanowitz had organized a more traditional quartet and then picked it apart and scattered its elements. But there’s no need to delve for meaning in the fact, say, that Toogood at one point spins offstage and then reappears spinning across behind the scrim. It’s not fairyland back there, but it is another space and affects our perception of her action.

Stuart Singer arrives even later than Toogood. He stops by while she has become embroiled in a fascinating solo voyage that includes a moment of strangely precise, jolting staggers, as if little explosions were happening unexpectedly under her feet. He almost immediately exits, looking back at her over his shoulder. Shortly, he returns to dance alone also. At the end, when Toogood has finished a sequence of big falling-apart leaps, whaling arms, and spins, and starts to back offstage, Singer reaches a hand to her from the wings, and on this comradely note, the lights go out.

In the coming and going of these four terrific performers, Tanowitz suggests a community in flux, with dancing as a metaphor for daily activities. Yes, they do pair up, yes, finally, all dance together (Tanowitz is masterful at building tension and interest without smacking you in the face with it). But the choreography preserves the performers’ individuality and the image they project of decision-makers working out their dance destiny.

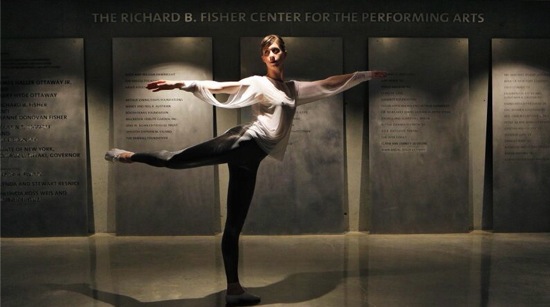

Lindsay Jones (minus the audience) in her intermission solo in the lobby of the Richard B. Fisher Center’s Sosnoff Theater. Photo: Cory Weaver

Tanowitz also has a surprise for those who thought that intermissions are only for coffee, chit-chat, or a breath of fresh air. In the lobby of the Sosnoff Theater in Gehry’s Richard B. Fisher Center, a tall, slim, dancer, Lindsey Jones, traverses the implied path between two big, square-off pillars that sit about twelve feet apart. Back and forth she goes, trying something different each trip, pausing occasionally. Whether stretching out her long legs in big shapely maneuvers or taking scrabbly little steps, she remains oblivious of the watchers; her world exists within ours, yet as removed, in its own way, as a painting hanging on the wall would be.

After intermission, The FLUX Quartet appears again on the apron at one side of the stage to play two Conlon Nancarrow string quartets (Nos. 1 and 3). In these compelling works, the texture can change dramatically from dense, intricate allegro passages to thinned-down circuitous melodies; in one moment, a violin is played so quietly and at a high pitch that it sounds like a mouse’s lament.

Since I saw the fascinating piece, Heaven on One’s Head, that Tanowitz set to this music a year ago February, she has, I believe, redesigned it. In it, Cloud, Crossman, Singer, and Toogood are joined by Jones, Andrew Champlin, Sarah Haarmann, and Vincent McClosky—all of them wearing Bartelme’s handsome red velvet shorts and tops.

It seems to me that Tanowitz’s propositions about the space and what we see or don’t see have become more compelling. When Heaven on One’s Head begins, the curtain pauses briefly when it has lifted only halfway up, and we see that dancers are already moving. Then, midway through the work, Toogood moves onto the stage apron opposite the FLUX musicians and directs her dancing toward the stage; now the curtain has descended so low that we see only the dancers’ feet or seated bodies. At another point, men start falling in from the wings on the musicians’ side. First, Singer drops into sight and is pulled back by invisible hands, then McCloskey, then Champlin, who recovers, hops offstage and is replaced by Crossman (I think that’s right). Champlin must fall again, because I recall Crossman, in plain sight, dragging him away. Just before the end, this motif recurs. So the stage extends its boundaries. What is happening that we can’t see? What does a partial curtain conceal?

I’m struck this time—not just by the inventive, changeable patterns and the juxtaposition of stillness and motion, but by the variety of steps that send the dancers into the air. In ballet, these have French names: grand jeté, sauté, assemblé, sissone, jeté en tournant, etc. Put simply, these are the basic ways anyone gets off the ground: leaping, hopping, jumping from one foot and landing on two, jumping from two feet and landing on one, making a half-turn as you leap. In addition you can smack your legs together in the air, bend them, or keep them straight. In Heaven on One’s Head, Tanowitz employs all these steps at one time or another, but they don’t look the way they do in a classical ballet; her dancers may tilt their bodies in the air or hunch them over. Watching them, you don’t even see “steps.” You think “flying,” “vaulting,” “soaring,” “exploding into the air.”

Whether together, apart, clamped to a partner, lined up, scattering, rushing away, or falling to the floor, these are people you want to keep watching. They make your pulse quicken and slow down. What’s the story? It’s what they are doing. What are they doing? That’s the story.