Brian Brooks Moving Company brings new and old works to the Joyce Theater

If I were asked to put choreographer Brian Brooks into a category, I’d have to coin a term: maximinimalist. His works are economical in terms of material and/or structure, but enriched into expressiveness by the ways in which he builds them.

Take his 2010 Motor, which made an unexpected appearance on Brian Brooks Moving Company’s early June season at the Joyce in place of the scheduled Counterpoint. In this duet, Brooks and Matthew Albert hop for the duration of the dance. While Jonathan Pratt’s score—now eerie, now big and celebratory— alters their terrain, the two men remain almost always side by side and quite close together, leaning slightly forward as if in a race. The hops are small, barely off the floor, and it’s amazing to see the variations that Brooks squeezes out of them. Now the men lift one leg in back, now in front; now they travel only slightly, now they cover more ground. Now they edge forward, now they back up. The distance between them increases, then decreases. They voyage along diagonal paths and curving ones. Every now and then, a low leap lands them on the other foot. If you chalked the bottoms of their feet, you’d end up with a striking pattern on the stage floor.

Brian Brooks’ Division. (L to R): Matthew Albert, Haylee Nichele, Carlye Eckert, and Ingrid Kapteyn. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The structuring device of the entrancing Division (2014, a New York premiere) is a prop—or rather, props. Each of the six dancers who begin lined up on one side of the stage carries a balsa wood panel that measures about 3 x 4 feet. Carlye Eckert, Marielis Garcia, Ingrid Kapteyn, Haylee Nichele, Jeff Sykes, and Albert (especially wonderful in everything) are dressed like a team in baggy white shorts and shirts (costumes by Karen Young). Moving swiftly to a score by Jerome Begin, they form innumerable patterns and intersections that build in complexity—all based on the nature of the panels. These become obstructions, fences, roofs, arches, bridges to dance past or be deflected by, but never any one of these for long. Exiting and re-entering, the dancers may exchange panels and collaborate with others in handling them. They’re not building anything, just engaged in a project that demands skill, timing, and cooperation. In other words, a dance.

Brian Brooks’ Torrent. Foreground: Haylee Nichele and Jeff Sykes. At back: Daniel Ching (L) and Dean Biosca. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

When Brooks choreographed Torrent in 2013 for Juilliard Dance, he had to wrangle twenty-four second-year students. His title and structure derive, I imagine, from that slew of young dancers.

For the Joyce stage, he pared the cast down to eight (adding Dean Biosca and Daniel Ching to the six already mentioned), but you still sense streams and pools of performers, who peel, one by one, away from a cluster, or drop out of a line that moves like a wave across the stage in order to dance alone or to form pairs or trios. When all walk to the front of the stage, and Garcia goes into her private world for a few sections, none of the others notices her; before long, she is reabsorbed into the general flow. Often one or two people will simply walk or run across the stage and disappear. The rest of the time, they dance expansively—their arms scooping up air, their legs slicing and whipping through it. They spin often, creating pockets of turbulence. The music, a Vivaldi concerto from The Four Seasons “recomposed” by Max Richter, subjects springtime freshness to electronic slipcovering.

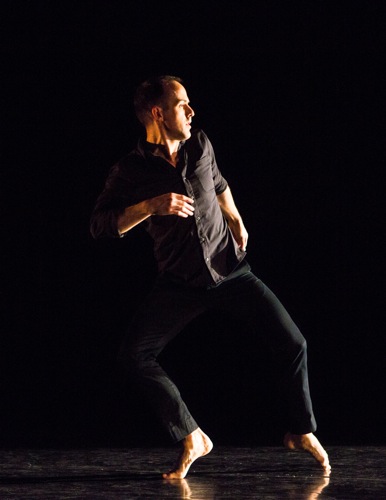

I didn’t absorb the title of Brooks’ brand new solo, Retrograde, before I watched it. So I wasn’t paying the kind of attention you pay when you think a performer is running a dance sequence backward. The atmosphere is initially dark. Lighting designer Philip Treviño has focused a strong light from one far corner; the diagonal path it lays on the floor gradually widens as it reaches almost to the opposite corner, where Brooks stands at its edge. Darkness and smoke surround the lit area. Along this path he travels, making very little progress in relation to the amount of activity he’s churning out. To music by John Luther Adams, he moves his arms in sinuous ways, turning often to face new directions. He doesn’t show us force or space-devouring movement; often he’ll bring one foot down beside the other into something close to a ballet dancer’s fifth position. He might be treating movement the way you’d patiently untangle a snarled series of cords. In the end, he’s close to the source of the light, but there’s a dark space of floor he won’t cross. Was that where he began, way back before the dance he decided to show us?

For Brooks’ other world premiere, Sudden Lift, the eight dancers (Dylan Crossman and David Norsworthy join the original six mentioned) wear gleaming silver attire by Young—shorts plus tops that bare much of the performers’ backs. To music by German composer-pianist Nils Frahm that mingles piano and electronic effects, and caught in Treviño’s imaginative lighting, the dancers glimmer as they shoot on and off the stage, or stay to pair up or make group patterns. Once, when Nichele is simply walking, Crossman leaps onto the stage like a lightning bolt (he must have run and jumped from offstage to be that high the second he flashes into view).

The dancing is fluid, sometimes airborne. It has a swing, a lift to it, although at times, the terrific performers appear tumbled by wind. It took me a while to notice something intriguing. In Sudden Lift, Brooks seems to be working with a fairly limited vocabulary of movements, yet the way he twists these, interpolates them, passes them around, modulates and varies them creates a rich choreographic impression. The effect is akin to that of a beautifully chosen vocabulary of words; everyone using it can make it sing differently.