New York Theatre Ballet presents classics and new works at St. Mark’s.

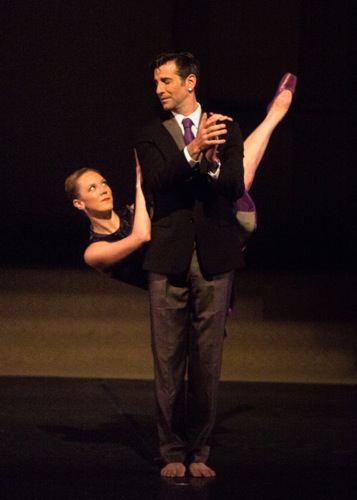

Steven Melendez (L) and Michael Wells woo Amanda Treiber in Frederick Ashton’s Capriol Suite. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

A year ago, New York Theatre Ballet was forced out of its longtime home in the Murray Hill neighborhood, and founder-director Diana Byer was distraught (do I need to discuss the insane prices in Manhattan real estate?). The outcome was a happy one; the company has relocated its studio to the second floor space in St. Mark’s Church in the East Village, and in the company’s June season, pointe shoes are having their day in the church proper where mostly bare feet reign (although not on Sundays).

It’s a new experience to see this fine little company with its distinctive repertory in a non-proscenium space, and to be close to the dancers. There are, naturally, both disadvantages and advantages. For instance, there can be no backdrops for Antony Tudor’s great Dark Elegies (not that New York Theatre Ballet ever possessed those), but in the company’s recent program, “Legends and Visionaries,” the dancers we’re meant to see as the nobility in Frederick Ashton’s charming 1930 Capriol Suite, could sit on chairs placed on the altar platform and graciously descend the steps when they wished to spell the bouncy peasants in their dances. A nice touch.

New York Theatre Ballet in Capriol Suite. Visible (L to R): Steven Campanella, Rie Ogura, Nayomi Van Brunt, Michael Wells, Elena Zahlmann, and Steven Melendez. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Peter Warlock’s score for Capriol Suite invokes the dances described in Thoinot Arbeau’s 1589 dance manual, Orchésographie, in which an eager student, Capriol, quizzes the master as to steps and decorum. This clever early ballet by Ashton challenges the NYTB dancers—not just because the steps are intricate, but because the choreographer wanted us to see the aristocrats as cool and slightly pompous (which is hard to manage without overdoing it). The peasants kick up their heels in orderly glee, giving us occasional arch glances, as if we’re in on a secret. The costumes (William Chappell’s original design) downplay the class difference, even as they make it clear. All the outfits appear to have been cut from the same bolts of pink and beige fabric, but differences in the lengths of the women’s skirts and the men’s bloomers alert us to what we need to know.

Alison Brangwen, Rie Ogura, Stephen Campanella, and Mitchell Kilby romp to a basse danse tune amid flying skirts and lusty steps. Stephen Melendez and Michael Wells woo Amanda Treiber in a stately pavane—Melendez with a scroll (a poet for sure), Wells with a rose. Later Carmella Lauer, another lady with a long, wide-at-the-hips skirt joins these three in a “Pieds en l’air.” Elena Zahlmann cavorts with Campanella in a vigorous tordion, and all four men cross class boundaries to sport about in a “mattachins” and show how high they can jump before re-joining their partners.

Two smart new works grace this program: David Parker’s Two Timing and Gemma Bond’s Cat’s Cradle. Parker had the happy idea of having guest artist Jeffrey Kazin of the Bang Group perform Steve Reich’s Clapping Music, while Zahlmann creates the audible rhythms with her pointe shoes and heels. In the score, a single twelve-count phrase of claps and pauses is methodically altered (the first note keeps becoming the last one). The two performers move close together, always in counterpoint, and eventually the sound-making includes smacks on the floor and other forms of body percussion. It’s a virtuosic number, executed at a good clip, and Kazin and Zahlmann eye each other with the single-mindedness of mating birds.

Gemma Bond’s Cat’s Cradle. Entangled (L to R): Rie Ogura, Alexis Branagan, Mayu Oguri (above Branagan), Stephen Campanella, Nayomi Van Brunt, and Amanda Treiber (hidden). Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Cat’s Cradle is Bond’s second work for NYTB. An American Ballet Theatre dancer and a talented choreographer, she has choreographed a ballet that unequivocally illustrates its title. The eight dancers are divided into two trios and a duo and the members of these groups are bound together by a long piece of white fabric with built-in circlets that belt each individual dancer. To music by Karen LeFrak, Bond investigates the tricky games that can be played by two or three partners who must collaborate in creating spreading-out or curling-in images, and in twisting, ducking under, or vaulting over the link that connects them. You can see what they do as a series of games or a demanding job in a weaving workshop. Or as a romance with fetters that involve constant attention to one’s partner(s), as in the sequence for Lauer and Choong Hoon Lee. When all eight join in ingenious, smoothly executed patterns, you hold your breath for fear of tangles.

When I say that this NYTB program abounds in cleverness, I don’t mean to imply that it is without feeling. The remaining two ballets delve into deep emotions, however restrained the expression of these may be. One is Richard Alston’s lovely Such Longing, set to five Chopin mazurkas, two études, and one nocturne (all fluently played in the church by Michael Scales). Martin Lawrence, who danced in the work at its 2005 London premiere, taught the movement to the dancers, and Alston arrived from England to coach it, modify it, and add new material for the NYTB dancers.

In part because of the music, Such Longing brings to mind Jerome Robbins’s Dances at a Gathering, also set to Chopin’s piano pieces. As in that great Robbins ballet, Alston’s piece begins with a meditative solo for a male dancer. Melendez performs it magnificently, wandering introspectively, glancing about as if waiting for someone, suddenly dropping down to touch the floor. The choreography plays large sweeping, wheeling movements against small, sharper ones and explosions into big jumps (Melendez has impressive elevation and is very responsive to slight shifts in the emotional climate).

Such Longing shows four people Melendez, Treiber, Lee, and Ogura meeting in friendship, competition, and love, as if on an outing in the country together. When Treiber dances with Melendez, he bends her backward —over his thigh and in many other ways. Perhaps she’s swooning, or he anticipates her doing so. When he lifts her, he pushes her slowly upward (no preparatory jump on her part), and she seems to get lighter as she goes; it’s a beautifully tender moment. After he leaves, Ogura enters with sweet solicitude for her friend; she touches Treiber’s cheek, no questions asked, and they walk off together,

There’s also a slightly quieter duet for Ogura and Lee and a wonderfully complicated one for the two men. Alston has devised some remarkable competitive (yet musical) encounters for the latter; they’re in close contact with each other almost the whole time, and the duet ends with a handshake.

I’m greatly impressed by these dancers—their skill, their attention to style, detail, and nuance. But I find myself at times craving a little more from Lee and Treiber in Alston’s ballet. In her duet with Melendez, the excellent Treiber seems less aware of her partner at every possible moment than he is of her; her thoughts don’t register as clearly as his. Lee is a startlingly clear dancer; he slices through the air like a knife. That is wonderful to watch. But his face remains masklike; we know he can see (he has to), yet on another level, he doesn’t see the people he’s with and the space that surrounds him.

Carmella Lauer (center) in Antony Tudor’s Dark Elegies, with (L to R): Amanda Treiber, Nayomi Van Brunt, and Rie Ogura. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The other dance that delves into emotion—this time, one of grief—is Antony Tudor’s 1937 masterpiece, Dark Elegies. NYTD performs this dance (staged and directed by Donald Mahler) with a simplicity that’s deeply moving. Scales is again at the piano, this time accompanying baritone Darren Chase, who, dressed like the dancers and standing close to them, sings with beautiful gravity and resonance Gustav Mahler’s heart-wrenching Kindertotenlieder. You may not understand the German words or what lies behind Tudor’s premise that many children in this fishing village have perished, but you know that something terrible has happened and that these people are holding themselves together by taut and fragile heartstrings.

In wintry light (by Serena Wong) and in plain clothes (by Raymond Sovey after Nadia Benois’ originals), the people of the community mourn together. The first scene is called “Laments of the Bereaved,” the second, briefer one is “The Resignation.” Alexis Branagan, Giulia Faria, Mayu Oguri, and Nayomi Van Brunt join those already mentioned. From the moment that Ogura enters, traveling across the stage, with each foot brushing briefly back and forth against the floor between steps, you feel both hesitation and determination. When she leaves at the end of Dark Elegies, trailing the others, the same movement makes you think that she might be erasing footsteps the way one might both remember and let go of memories.

Rie Ogura (center) in Dark Elegies. Leaping (L to R): Carmella Lauer and Amanda Treiber. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

As is the case in Tudor’s dramatic ballets, the dancers hold their arms down; when they suddenly open them or hold them up to heaven, the change is all the more moving. These are not people who wail openly; they are sterner with themselves. You feel their despair in the way Lauer crumples into a bundle in Melendez’s arms when he lifts her, and the way he repeatedly supports her with a hand behind her neck, as she leans rigidly back bent only at the knees. The men express their emotions in larger ways: Campanella seeming to question fate, Lee erupting in harsher, angrier movements, as if he would slay the air. In her solo, Zahlmann visits each of three seated trios and bows to them, as if to excuse her display of anguish, or, perhaps, to thank them for their sympathy.

And along with giving and receiving these particular testimonies, the people form chains and circles and dance in familiar ways, laying their sorrow to rest in the only way they know. The NYTB dancers perform Dark Elegies scrupulously and sensitively. A great achievement.

“taut and fragile heartstrings”, what a lovely phrase and how it tugs at my own heart. Thank you Deborah, comme toujours.

Hi Deborah,

Thank you for your excellent, moving, review of the recent performance of the New York Theater Ballet. Especially of Tudor’s Dark Elegies . You are one of the few critics who are as clear as crystal in your observations, making me feel as if I were there with you watching the performance. And, so important, what you write is constructive for all involved in the performance.

Again, thank you, Richard Gibson

Wonderful review – wish I could see this program. . .