Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in its final season.

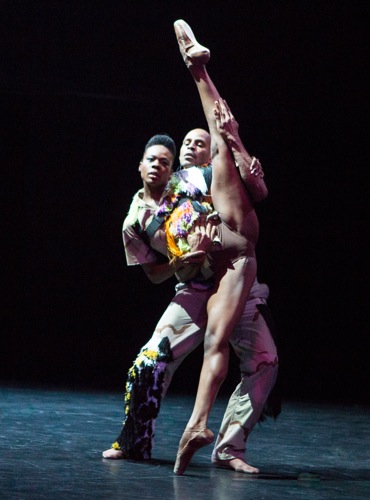

Cedar Lake dancers in Richard Siegal’s My Generation. Vânia Doutel Vaz with Guillaume Quéau (L) and Ebony Williams with Joaquim de Santana. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The news that Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet was folding came in March. The entries on the company’s Facebook page seethe with shock, sorrow, and profound disappointment from those who cherish Cedar Lake’s dancers. And those dancers were rightly cheered at their farewell performances at BAM.

What happened? No one is revealing the details. A spokesperson for the company’s founder and principal funder, Nancy Laurie, gave an statement to the New York Times that raised more questions than it answered: “Over the past decade we have dedicated substantial resources to Cedar Lake. Unfortunately, prevailing circumstances make running Cedar Lake no longer viable in this community.”

Laurie, a Walmart heiress, is said to have been responsible for over seventy-five percent of the company’s budget. Thinking back to another wealthy ballet patron, Rebecca Harkness, who shut down the Harkness Ballet in 1964, I can imagine that Cedar Lake’s directors either failed to line up other funding sources, or that potential contributors figured, “What the hell, she’s got money; let’s help less fortunate groups.”

And it was, indeed, a fortunate group. I first saw its beginnings as the Cedar Lake Ensemble in late December of 2003, when it performed at Dance Theater Workshop. Three of the five pieces on that program were by the company’s artistic director, Jen Ballard, a name new to the New York stage, and three of the dancers were from another company that had disbanded: Eliot Feld’s Ballet Tech. One of those three, the terrific Nickemil Concepcion, is still aboard the sinking ship (another founding member, Jason Kittelberger, fairly recently dropped off the roster).

In 2005, when former Ailey dancer Benoit-Swan Pouffer took over as artistic director, the company moved into two renovated buildings on far-west 26th Street that included a handsome black-box theater. Pouffer could invite choreographers from Europe, some of whose work he knew from his pre-Ailey career in France, and the dancers (with 52-week contracts and health insurance) could luxuriate in the excellent new quarters, as well as rising to new challenges that included touring and unfamiliar ways of moving. Over the years, when auditions were held, hundreds showed up.

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Alexander Ekman, Didy Veldman, Stijn Celis, Jo Strømgren, Jiří Kylián, Ohad Naharin, Crystal Pite, among others, created (or in Naharin’s case, adapted) works for the company that was renamed Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet and boasted fifteen stunning dancers. You had to head west on 26th Street to see what new boundaries they were crossing.

Pouffer resigned in 2013, and since then, former ballet mistress Alexandra Damiani has been artistic director, aided by Brian Reeder as rehearsal director. I was buttonholed in the BAM lobby by someone who needed to make sure I knew how valiantly Damiani had been holding the enterprise on course until the end by making sure the works were polished to a high shine for Cedar Lake’s last two engagements.

That was evident. At BAM, the company presented two programs of three works each; some of these were double cast. Those company members that I saw in Program A danced as if every moment were their last night on earth and they wanted to make it one to remember.

Looked at from one perspective, the program order seemed slightly askew. Richard Siegal’s world premiere, My Generation, which came first, has all the earmarks of a closer. On the other hand, Crystal Pite’s elegantly and ardently somber Ten Duets on a Theme of Rescue (2008) showed just how sensitively the dancers could perform, and the last work on the program, Johan Inger’s 2014 Rain introduced elements of kinky humor in ways more controlled than Siegal’s bash. So perhaps the thinking was to flood the audience with eye-popping costumes and virtuosic craziness and then announce, “we can also have dark thoughts and allude to postmodern gender politics.”

Siegal (best known here for his appearances with William Forsythe’s companies and for his own Germany-based group, The Bakery Paris—Berlin) took his title from The Who’s 1965 hit, “My Generation.” The song is part of the recorded score for the dance, along with three pounding—and intriguing— techno numbers by Atom™ (Uwe Schmidt). A look at a montage video of The Who (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=594WLzzb3JI) gives a sense of the pacing and flurry of Siegal’s dance. No guitar swinging and smashing, of course, but there’s a pretty amazing performance by Matthew Rich (a Cedar Laker for ten years). Lip-syncing at us, strutting, flouncing, banging out his moves, his long hair and pieces of his outrageous costume swinging around him, he’s crazed and unstoppable. The curtain has to descend on him. It almost immediately rises again, however; and the stage lights are turned on us as the dance begins to end for sure.

Whatever generation(s) Siegal is putting onstage, its members are not your ordinary hippies (for one thing, the women are on pointe). Flamboyant, erratic, glamorous, the twelve dancers add to, subtract from, or change their attire almost every time you see them. Bernhard Willhelm’s costumes, not all of them becoming, have things patched erratically onto them and hanging from them. Cotton meets satin meets fringe. Fashion stylist Edda Gudmun collaborated with Willhelm. Stan Pressner’s lighting design adds to the gaudy imagery.

The dancers are often confrontational. They put their hands on their hips, take a stance, and fix hot stares on us. “We see you, baby,” they might be saying. “Take a good look.” This is such a cliché that I’m not sure whether Siegal meant to send it up, or whether he thinks it an important part of the “scene.”

Navarra Novy-Williams playing with (L to R) Jon Bond, Joaquim de Santana, and Guillaume Quéau in My Generation. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

But they do dance, and how they dance! The choreography ventures into extremes of strength, flexibility, and partnering. They spin, they swing their legs insanely high. The pointe shoes are almost beside the point, unless they stand in for stiletto heels and small weapons. Navarra Novy- Williams, alone onstage at the beginning of My Generation, isn’t alone for long. Jon Bond joins her, then Joaquim de Santana and Guillaume Quéau. She’s a party girl, although maybe they get a little too possessive. The men leave her in the lurch, but almost immediately return. Some hip action on their part turns the spectators on: “Whooo!!” they yell.

Ebony Williams, another ten-year veteran of Cedar Lake, and a favorite of the audience, pairs up with de Santana. To “I Love You Like I Love My Drum Machine” (Atom™), she stares as if daring us to come onstage and inspect her at a closer range. Quéau partners Vânia Doutel Vaz in similar outré ways. In this hopped-up ballroom, people come and go, stand and watch, as colorful as birds in an urban jungle. In the final Atom™ number, a man’s voice begins by announcing, “Zwanzig hertz, und ich bin meine maschine;” the music gets denser and the units of frequency called out by this self-identifying machine increase from twenty to millions. The dancers clap along. The stage ought to explode from all this voltage, but it holds steady.

Ten Duets on a Theme of Rescue is one of Cedar Lake’s most enduring commissions. Unfortunately, it is not seen at its best on a proscenium stage like the Joyce. In Cedar Lake’s own theater, you could see that it was various of the dancers who, from time to time, repositioned some of the tall standing lamps that form a semicircle around the back of the stage. In Jim French’s purposely dim lighting, all you see the first time this happens is a light being moved by invisible hands.

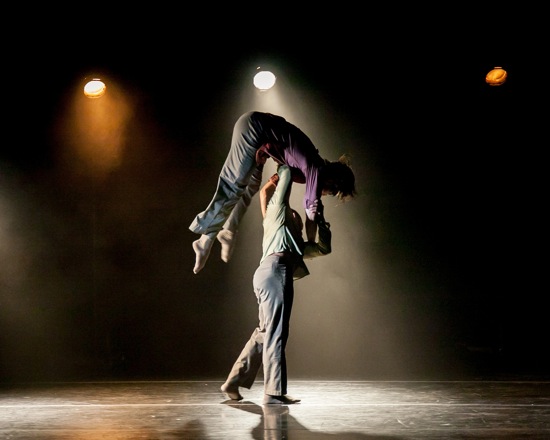

Pite’s work employs a small cast (the one I saw: Bond, Concepcion, Quéau, Williams, and Ida Saki) and is set to music drawn from Cliff Martinez’s score for the film Solaris— quietly ringing sounds with urgent repeated rhythmic motifs,. The structure of the dance reflects the title in various ways: saving another, saving oneself, being saved. Two duets are struggles, the first between equals—pushing each other down, pulling apart, dragging—the second with one person stronger than the other. In the shadowy lighting, I thought that the second pair was Concepcion and Quéau and marveled at how Concepcion can swing his partner around his body, bending and twisting to make it happen.

The movement that circulates the five performers through ten duets is driving, pitted with pauses, and always expressive. Whether combative or tender, the dancers move their bodies with sinuous care as if adapting in advance to the next encounter. In at least one partnership (for Bond and Williams), two people dance side by side in vigorous unison. One duet bleeds into the next. The most remarkable is one for Bond and Saki. She walks slowly across the stage in a path of light, one hand trailing behind her. Bond follows her, running in place getting almost nowhere, reaching for her hand. By the time he touches her, he’s collapsed at her feet. As he makes his way offstage, Williams enters and backs Saki into a very different sort of duet. Facing each other, gentle at first, they might be having a quiet discussion; it’s hard to tell who is manipulating whom.

Inger created Rain Dogs for the Basel Ballett in 2011 and Cedar Lake’s dancers offered its New York premiere. Set to seven songs delivered in Tom Waits’s gravelly voice, it organizes and disorganizes a squad of nine into what suggests an urban dystopia. The dancers wear street clothes. Smoke appears and fumes or clouds pass on the backdrop via Peter Lundin’s lighting.

Concepcion begins the piece alone, switching on a boombox, and responding with nervous, eccentric excitement to what he hears. He’s in front of the curtain, edging along it when it lifts to reveal a small set piece containing more audio stuff (strangely not made use of ) and an assembly line of dancers stretching from the front to the back of the stage.

Gesturing percussively, dropping in and out of the line, they convey the feverish consumerism of Waits’s “Step Right Up” as it marches into fantasy (“Swim in it, sleep in it,/ Live in it, swim in it, laugh in it, love in it/Removes embarrassing stains from contour sheets, that’s right/

And it entertains visiting relatives, it turns a sandwich into a banquet/ Tired of being the life of the party? Change your shorts, change your life. . .”). Waits growls out “Make it Rain,” and while Saki and Williams move slowly, deeply, and sensuously, and Quéau plays odd man out, fake precipitation drifts down. He and Saki glue their lips together, but eventually it’s the two women who embrace, while he jitters around them. Joseph Kudra dances with Saki, Bond with Jin Young Wong, but no relationship endures.

There’s a gimmick. When Waits croaks out “Frank’s Good Years,” a stuffed poodle waits alone in a spotlight, perhaps standing in for the chihuahua that “Frank” hated; perhaps too the smoke that begins to pour from the dog signifies the fire that this small-souled man of the song set to destroy his house and all in it. At some point, all the dancers but one (Doutel Vaz, as I recall) collect in a corner, and trudge across the stage, softly clapping their hands; they run right over the woman, who’s on all fours, and never look back.

At some point, I begin to wonder what on earth this dance is trying to tell us. Waits’ songs paint a wretched picture of a world far less sanitized that the one Inger creates, considering how often the dancers form neat patterns (men and women facing each other, or all of them ranged along the front of the stage, sitting and staring at us). A line from “Hoist That Flag” may add fuel to Rain Dog’s final section: “Well we stick our fingers in/ The ground, heave and/ Turn the world around. . . .” The male dancers have acquired jackets along the way, and now the process of changing the picture begins. Concepcion returns in his underwear and socks, then in a dress just like Doutel Vaz’s. As the dancing goes on, with Waits’ woozy voice dealing with “The Piano Has Been Drinking,” the dancers gradually change their gendered attire. It’s with the men in dresses and the women in black trousers and jackets that they clump together, lean back, and pump the air. Concepcion cries out the song’s last line “Not me!”

It’s a pleasure to watch these marvelous dancers adapt to the demands and whims and insights of the choreographers they work with. They know when to blaze outrageously, when to smolder quietly, when to chill. They stint on nothing. I am sure that they’ll all find jobs elsewhere. But not, of course, together. To our sorrow.

One of my favorite headlines has long been one Deborah wrote for a review of the Harkness Ballet in The Village Voice that she might well have been tempted to use for this piece: Lady Bountiful Strikes Again. I’ve not always agreed with her on the choreography for Cedar Lake, but once again it’s a pity that these fine dancers have been set adrift on short notice by the whim of the person holding the purse strings and that one of the rare outlets for a different approach to dance has been closed. (And I know Deborah wrote that headline, as I asked her and she said that she always wrote her own headlines, unlike most papers, where the writer has no say in them.)

Individual donors of great means are always capricious. One day you are in — the next you are out. They may ultimately insist upon a broad base of funding (so as not to be the principle contributor — though that stroked the ego in the beginning) that simply does not exist for contemporary dance save for the most popular companies like Alvin Ailey. Even Paul Taylor struggles to get enough money in. Its dance in America.. As MC said, “Ya gotta love it.”