Pascal Rioult celebrates the centennial of Edith Piaf’s birth in a nightclub setting.

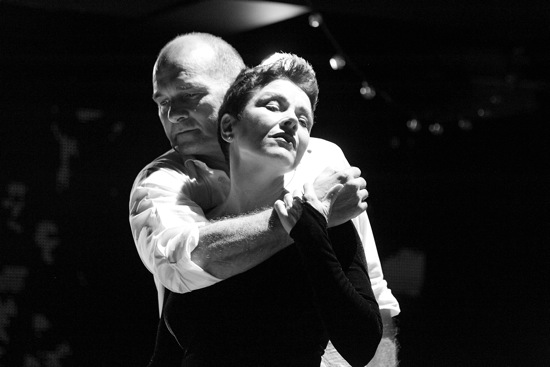

Christine Andreas (singer) and Charis Haines (dancer) in black-and-white as Edith Piaf in Pascal Rioult’s Street Singer. Photo: Paul B. Goode

To get myself in the mood to write about Pascal Rioult’s Street Singer, a work celebrating what would have been Edith Piaf’s hundredth birthday, I dug up a relic from my family’s past: a 10-inch LP from the 1940s, Chansons Parisiennes (it had cost three dollars) and listened to Piaf sing “La Vie en Rose” (by Louis Louiguy, Mack David, Marcel Louiguy, and Piaf). How enthrallingly that voice—now raw-edged, now defiant, now mournful—hymned and cursed love’s ecstasies, pitfalls, and tragedies. When I was a teenager, listening to her made me shake in anticipation.

Pascal Rioult must have had a similar encounter with Piaf (plus he’s French), and Street Singer, a the music-dance-theater piece that he created in collaboration with Drew Scott Harris (dialogue and staging) and music director Don Rebic, vividly evokes her power. It’s always a treat to see a choreographer push himself in a new direction, and who would have imagined that a one-time member of Martha Graham’s company and a choreographer of works set to masterpieces of music or edgy works by contemporary composers would enter so boldly and so affectionately into an intimate relationship with cabaret?

Street Singer was not presented by RIOULT Dance in a theater. Instead, the audience members in 42West Nightclub sit at tables on either side of a runway that leads to a very small stage, part of which is occupied by Rebic (at the piano), Patrick Farrell (accordion), John Miller (bass), and Chris Parker (percussion). Projections (by Brian Clifford Beasley) of grainy old photos and newsreels occasionally appear on the back wall. The bar lounge (with live entertainment) opens an hour before curtain time. I’m feeling happy already, and a man sitting at my table has ordered one too many glasses of wine (merci, Monsieur).

Without singer Christine Andreas’s immense gifts, these evenings could not have been as enjoyable as they were. Andreas—whose career encompasses performing in Broadway musicals, symphony orchestra concerts, and cabarets— channels “La môme Piaf,” the street sparrow, superlatively. Wearing (as Piaf did) a simple little black dress, she digs deeply into the mood of each song. Her voice is powerful, her French accent excellent. Nor does she just stand and sing; she also strides along the runway, occasionally moving among the dancers or addressing her words to them. The lights (by Jim French) imply her various milieus, as well as occasionally isolating her in a spotlight, which suits the atmosphere of a club and also suggests in its surrounding gloom the darkness that often crowded into her life. Street Singer begins and ends with that most blazing of songs associated with Piaf: Charles Dumont and Michel Vaucaire’s “Non Je ne Regrette Rien,” with its underlying, but inexorable rhythmic march and its message of beginning afresh and to hell with the past—joys and griefs alike.

Rioult himself not only embellishes Andreas’s rendition of “Sous le Ciel de Paris” by reminding of the artists and poets who lived and worked there, and speaking some of the song’s lyrics. He also dances briefly, with wonderfully leonine power. No longer the slender young guy he once was, he movingly shadows Piaf’s great love, the champion boxer Marcel Cerdan, who was killed in a plane crash, and simply by turning his back to the action and then coming forward again, he evokes the ghost of the man and the days of love that Andreas sings about.

The members of RIOULT Dance (six men and four women) are kept busy illustrating the events in Piaf’s life and career that colored her songs. Pilar Limosnar’s costumes aid in their many transformations. Sara Elizabeth Seger, Candace V. Perry, and Charis Haines cluster and flutter around Catherine Cooch, evoking the years little Piaf spent with her paternal grandmother, who operated a brothel in Normandy. Sometimes the dancers fleetingly assume roles or reveal crowd behavior. When Piaf, manipulated by her father, becomes a street performer, Jere Hunt steps out of the group to command her: “Sing!” and “louder!”

We see various of the dancers (in addition to Hunt, the men are Brian Flynn, Michael Spencer Phillips, Sabatino A. Verlezza, Holt Walborn, and Louis Roccato) pair up and glue themselves to their partners in a ballroom hold, hips swinging raunchily, as they dance to the bouncy 3/4-time of “la java” (music by Rebic). After Andreas sings Cole Porter’s “My Heart Belongs to Daddy,” and Flynn does a spectacular, lip-synching turn in elegant drag, we assume that Piaf has graduated from the streets to classier clubs (also, I think, to the Folies Bergère). The dancers perform a cleverly arranged can-can (again to Rebic’s music) with a kick line and splits for all. After Cerdan’s devastating death, Piaf apparently works as a waitress (this isn’t quite clear), and Rioult created a dizzying routine that involves the dancers, dish towels, and a rapid, increasingly tricky passing of plates.

The dancers also express Piaf’s desires in more formal terms. “I was a hunter for love,” Andreas confesses, and the men swing her high in Marguerite Monnot’s “La Valse de l’Amour.” Charis Haines appears as her remembered younger self, shadowing Andreas’s gestures and dancing giddily. Seger and Hunt perform an almost scarily violent duet that seems only partly consensual and is set, ironically, to “La Vie en Rose,” with its rose-colored-spectacles perspective on love. Some of the dancers cage or tempt the singer, as she consoles herself after Cerdan’s death with drugs and liquor.

Surrounding Christine Andreas: (L to R) Michael Spencer Phillips, Louis Roccato (partly hidden), Holt Walborn (partly hidden), Charis Haines (foreground), and Sara Elizabeth Seger. Photo: Paul B. Goode

Events shift with the overlapping swiftness of a montage—sometimes confusingly, always intriguingly. Through it all, Andreas stands fast in Piaf’s whirlpool of a life. She speaks about such controversial subjects as her (i.e. Piaf’s) performances in German prisoner of war camps (she smuggled prisoners out disguised as her band members, she says, as one too many dancers swiftly cross the stage in her wake). Andreas magnificently expresses the trajectory of Piaf’s life and life in music—from the hope and promise of Norbert Glanzberg’s “Mon Manège à Moi” (“You make my head spin/ My own carousel is you”) and Monnot and Piaf’s hopeful “L’Hymne à L’Amour” (a duet for Haines and Phillips) to the raging sadness of “Padam Padam” (Glantzberg and Henri Contet) and the bitter sarcasm of “Milord” (by Monnot and Georges Moustaki). At the end, Andreas reprises “Non Je ne Regrette Rien,” while dancers pass by like shadow images in her memory, and the regret that she denies feeling slips into her voice, despite that final brave “Je me fous du passé!”

I think I’ll listen to that record again, or watch Piaf defiantly flickering through her sorrows on YouTube. She didn’t live to see 100, or even half that. But her singing is on its way to another century. And thanks to Pascal Rioult for reminding us of that.